Canada: Universities need to enrich the world, not just the few

Universities that benefit from taking the best and brightest from developing economies could help re-balance global inequality.

Developed economies benefit immensely from the flow of international students. Picture: Wan San Yip, Unsplash. : Wan San Yip, Unsplash.

Developed economies benefit immensely from the flow of international students. Picture: Wan San Yip, Unsplash. : Wan San Yip, Unsplash.

Universities that benefit from taking the best and brightest from developing economies could help re-balance global inequality.

Many universities in developed economies seek greater and more equitable collaboration with their counterparts in the developing world. In doing so they hope to build a more just, sustainable, resilient and thriving world.

That would be inspiring if it came to pass. But such high-minded ideals ignore the fact that universities and developed economies have been complicit in what is referred to as “immigration colonisation”, namely how the reputable universities from the richer countries recruit students from around the world, especially from low and middle-income countries.

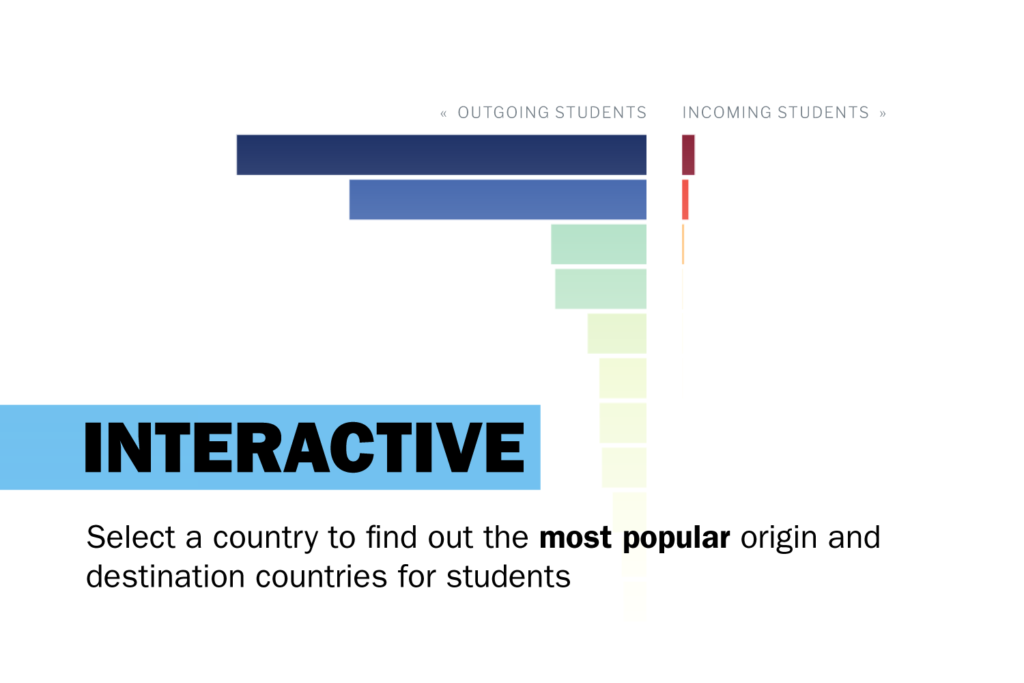

The benefits to countries in the developed economies are significant.

In many countries, international students are allowed to work while they study; post-graduation work permits give students work experience; and paves the way to permanent residency. According to the Canadian Bureau for International Education, 60 percent of international students will seek permanent residency in Canada after their studies.

For many academic institutions, recruiting large numbers of international students is a vital source of revenue. With stagnating domestic student enrolments, universities and colleges have been left with practically no choice but to recruit more students from overseas in order to financially sustain themselves.

International students pay significantly higher tuition fees than domestic students. More international students also means that the university scores higher on criteria that contribute to global university ranking.

Students go to richer countries for a variety of reasons, including world-class education opportunities, a welcoming environment, and quality of life. Viewed from the perspective of international students, migration is an individual choice related to where they study, live and seek prosperity.

Viewed from the perspective of source countries, however, and through the lens of sustainability and resilience, universities are complicit in immigration colonisation.

Universities in developed economies are not directly colonising other countries, of course. But they are helping their own country meet its future needs by directly compromising the ability of source countries to meet their needs. This reduces long-term resilience by removing vital capacity that is needed to drive prosperity.

However, the effects of immigration colonisation can be offset by those universities promoting equity with international students and their host countries as opposed to focusing their equity and diversity work solely on their campuses.

Such a commitment could facilitate capacity development, defined by the United Nations Development Programme as when “individuals, organisations and societies obtain, strengthen and maintain the capabilities to set and achieve their own development objectives over time.”

This is not about universities in the West embracing a ‘saviour’ role. Rather, efforts at collaborative capacity development need to be responsive to the 2005 Paris Declaration and the 2008 Accra Agenda on the effective use of aid, and at the invitation of communities in developing economies. These efforts need to be locally-led while being globally-served, as opposed to the other way around.

An offset could help to reduce resilience inequality by providing greater access to education. The value of technology in reaching students has been demonstrated since the start of the pandemic. We may be arriving at a point where a technology-paved path allows greater access to education for all. Leveraging technology constructively in partnership with technology providers opens up avenues for universities to develop better access to education for more isolated populations.

An offset needs to engage with diverse populations. Impact at scale requires leveraging everyone, not just faculty and students. Consider if universities used the offset to build a ‘resilience corps’ – a group of difference-makers that will have lasting impact through hands-on and grassroots-led actions.

The offset needs to be fair. One way to approach the investment is for universities to align with the UN agreement by countries to commit 0.7 percent of annual gross national income towards international assistance work.

If a university has revenue of US$2 billion, this translates to an annual investment of US$14 million in 2021-2022. Extrapolated to all North American universities, it could represent investment in low-to-middle income nations in the order of US$4.7 billion.

Dr Murali Chandrashekaran is Vice Provost International at University of British Columbia, Fred H. Siller Professor at UBC’s Sauder School of Business. He also serves as the Director of the Collaborative for Urban Resilience & Effectiveness (CURE), conceptualised as a global collaborative to mobilise talent, knowledge and experience across disciplines, colleges/universities, community organisations, cities and corporates to drive inclusive urban prosperity, innovation and development. Dr Chandrashekaran declared no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.