Internationalisation or intellectual colonialisation? A look into Asia.

Nursing students are potentially leaving the country to meet the health labour market overseas : Nugroho Nurdikiawan Sunjoyo

Nursing students are potentially leaving the country to meet the health labour market overseas : Nugroho Nurdikiawan Sunjoyo

Internationalisation or intellectual colonialisation? A look into Asia.

Universities, already encouraged to self-finance in the face of declining government funding, faced even more uncertainty when the pandemic hit. But few strayed from their strategy to monetise the growing global student market.

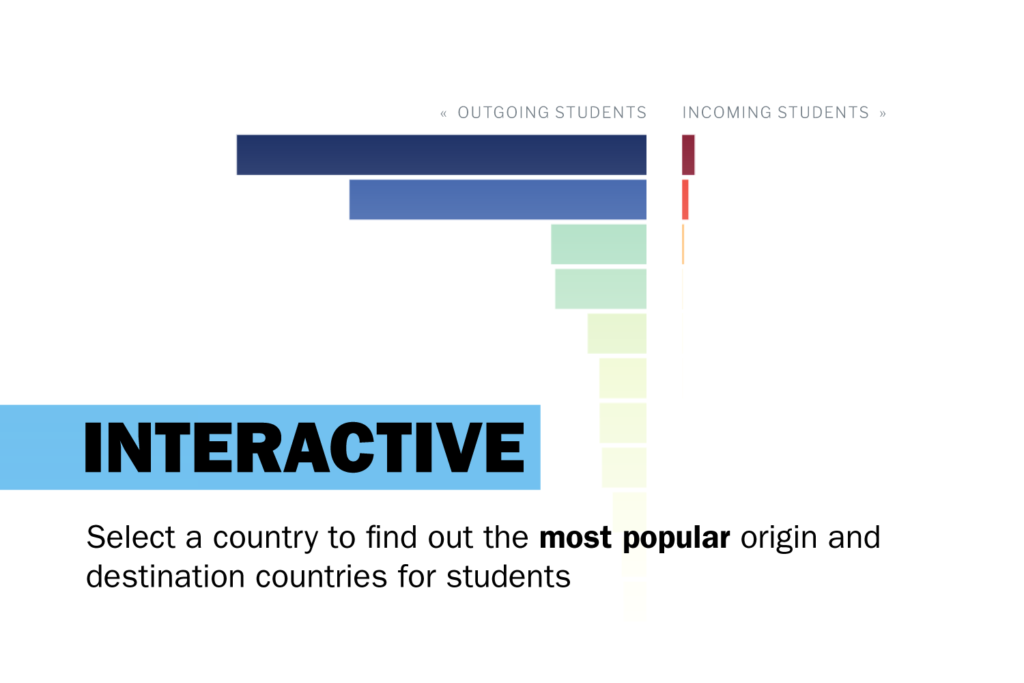

In the Netherlands, there is one international student for every four domestic students. Canada’s Immigration Refugee and Citizenship data shows that in 2015 to 2016 and 2019 to 2020, the number of Indian students studying there increased by 350 percent. Meanwhile, the UK’s Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) reported a 220 percent annual increase of Indian students enrolling in UK universities.

In Asia, many international programmes are provided by branches of UK universities. By 2021, there were 17 British universities in 27 countries around the world, providing education for approximately 60,000 students. The University of Nottingham Malaysia was opened in Selangor, Malaysia in 2000 catering to more than 5,000 students via the private university model. Newcastle University partnered with the Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT) and created the Newcastle University International Singapore (NUIS) to offer medical degrees in Malaysia through NUMed. In 2006, the Xi’an Jiaoting-Liverpool University (XJTLU) was founded in Suzhou, China reaching approximately 14,000 students in 2019.

It’s a trend that Adam Habib, Director of the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London says is accelerating the brain drain in Africa and Asia, weakening their intellectual and institutional capacity to deal with the pandemic, climate change, and inequalities.

Habib cautions that UK universities are inadvertently taking away intellectual capacity from economically-developing countries as former students marry, find work abroad, and eventually stay.

Such partnerships are, for Asian states, part of neoliberal aspirations to become ‘world class’. What is deemed ‘world class’ is constructed through international university rankings agencies like Quacquarelli Symonds and Times Higher Education. These rankings, after all, are prerequisites for Asian universities to tap into regional student markets by opening up their own English-based undergraduate programmes.

However, there is little ‘authentic’ intellectual and institutional capacity in Asia to begin with. For many countries in Southeast Asia, universities and hospitals were inherited from colonialist regimes. In Indonesia, independence movements of the early 20th century were mobilised by intellectuals and scientists who received a European education and were exposed to modern nation-state ideas.

Historically, Asian societies have been dealing with contradictions relating to the formation and spread of intellectualism, including how it reproduces new kinds of social inequalities between English-speaking Asians and their local counterparts.

In the meantime, at least in India and Indonesia, since the pandemic, governments and academic communities are increasingly realising the fundamental need to address these inequalities by leveraging on the science diaspora. These alliances between sojourners, who feel that they are very much Indian and Indonesian, and local intellectuals, encourage people to bridge more equal partnerships between science and technology. But this idea comes with new kinds of issues. Chinese diaspora and Confucius Institutes in Southeast Asia are viewed with suspicion, specifically as spreaders of the communist state’s propaganda through science collaborations seen as soft power.

On one hand, the sense of belonging of diasporic communities can teach us new ways to imagine more equal partnerships. On the other, developing a global consciousness is crucial in order to respond to upcoming global crises such as climate change and current ones like the COVID-19 pandemic; where borders are transformative and problems go beyond nation-states.

Perhaps it is less a question of whether “Northern” universities are draining Asia’s intellectual capacity than it is about deeper structural inequalities that have impinged on meaningful academic work and our ability to explain how all of us face fundamentally the same issues.

Regardless of location, academics working in social sciences and humanities face less and less funding, their campuses led by notions of surplus value as advocated by university leaders who think like CEOs, managers and administrators. There’s a tension between the public meaning of their work and the market mechanisms that hinder it.

So it is less a Wallersteinian issue of intellectualism, where the system between countries is hierarchical, led by former colonisers who dominate the world economy which translates into the stronger education capacity held by universities in developed countries over developing ones. And, it is more about the social reality that we live in an unequal world that exploits all kinds of labouring that tries to criticise and explain it, let alone undo it. A capitalist, social world that narrows the space to rethink our global future in meaningful ways. This space must be widened if we are to recuperate from the pandemic in ways that equalise power between the richest and poorest as well as between societies in environmentally-sound and long-lasting ways.

Perhaps, a realistic expectation is to work within the conditions that exist while continually acknowledging and explaining how new kinds of colonialisations—such as those made worse by market imperatives—surface through the modes of production of intellectualism in the world and in Asia. Ironically, or maybe consistently, it is the disciplines so often viewed as not monetisable that are able to critically unpack and explain to us how to find a solution. So maybe we begin there.

This article is part of a series entitled ‘Education brain drain’ on the ‘colonosation model’ of higher education where higher education institutions recruit the best and brightest from developing economies — with most never returning after graduation. To read the other articles visit 360info.org.

Inaya Rakhmani is an associate professor in the Faculty of Social and Political Science, University of Indonesia and Secretary General of the UK-Indonesia Consortium for Interdisciplinary Sciences (UKICIS). She is the Director of the Asia Research Centre, Universitas Indonesia and the Deputy Director of the Science and Education working group for the Indonesian Young Academy of Sciences. Her research interest is in how culture can hinder and enable the redistribution of and access to wealth. Dr. Rakhmani declared that she has no conflict of interest. The research was undertaken with financial assistance from the Indonesian Education Endowment Fund’s PRIME SOCIAL grant.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.