Malaysia: University campuses blending local with international

International campuses are learning by doing, integrating local knowledge and approaches to world-class institutions.

Blending local and international knowledge creates better learning: public domain image

Blending local and international knowledge creates better learning: public domain image

International campuses are learning by doing, integrating local knowledge and approaches to world-class institutions.

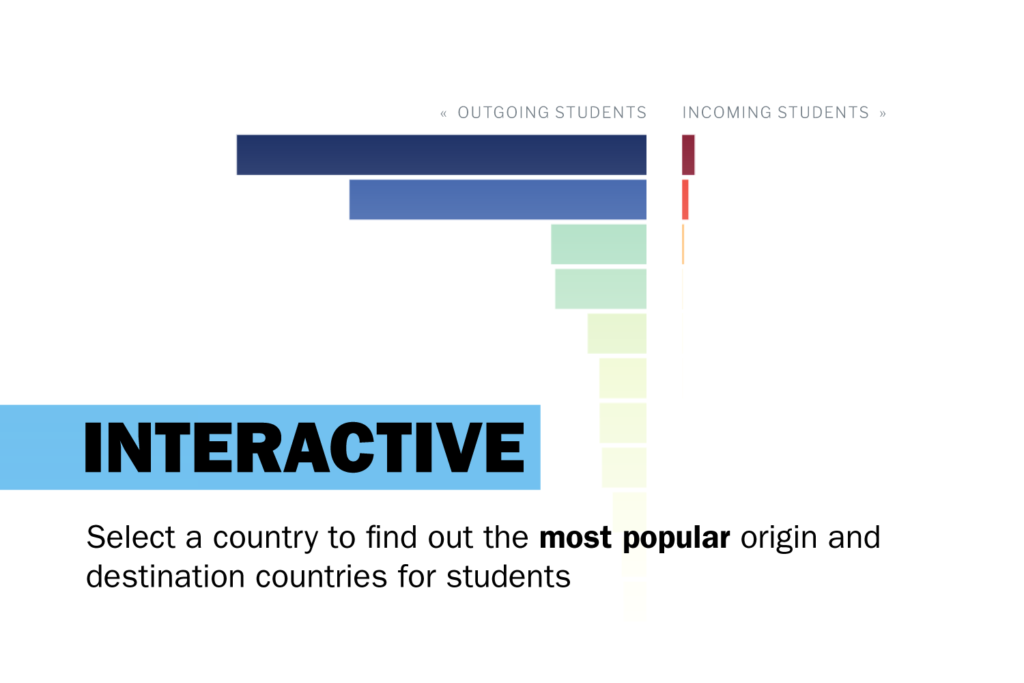

Universities have been slow to globalise. In the late 1980s there were only 30 or so international campuses: students moved, universities didn’t. Things started to change in the early 1990s and the following twenty years witnessed a mini-boom in international higher education operations.

The pace has slowed in the past decade — a steady stream of failures has prompted caution — but the number of global campuses continues to grow. Recent estimates range from about 250 to almost 500 overseas campuses from universities based elsewhere. The higher number probably includes one- or two-room operations within a host university; the lower number is more reflective of what we expect when we talk about a ‘campus’.

Universities from developed economies have dominated this emerging market. The three largest ‘exporting’ countries are the US, UK and France, with Australia and Russia active, but at a lower level. There is a parallel concentration in the importing nations: China and UAE are the most active hosts of international campuses followed a good way back by Singapore and Malaysia.

These international university operations aim to challenge the historically dominant flow of students seeking high quality education in developed nations. But these flows were already being transformed by the emergence of new centres of university influence, especially in Asia.

To a large extent, the success of international campuses in educating locally depends on how international campuses and their ‘parent’ universities shape their engagement with the host country.

In the early stages of offering degrees in off-shore locations, parent universities are focused on quality control. As they establish operations far from home, they need to ensure that the educational experience of off-shore students matches that of students at the base campus. There is a strong emphasis on curriculum consistency, and comparability in facilities and student experience.

Students and parents in the host country derive real benefits from this duplicative phase. They can be reassured that they are receiving a genuinely international education and that the degrees are not a second-rate reproduction.

But it also has its disadvantages. It is motivated by a push for consistent quality but, ironically, it raises quality concerns as neither students nor teachers have a stake in the content. Students can become restless about an imported curriculum that is disconnected from the local context. And good quality teachers cannot be expected to deliver a curriculum over which they have minimal creative control. This duplicative approach is a form of educational globalisation that involves little technology transfer.

In response to these limitations, universities have combined duplication with localisation. International campuses develop their own case studies, courses and even degrees to cater for local tastes and employment opportunities. These initiatives provide a richer, and more engaged, educational experience for local students, while benefiting from the quality assurance and reputational stature of the parent university.

But ‘localisation’ still carries the assumption of a ‘head office’ that is the primary driver of content, quality and standards. It still remains a Western-centric mode of operation.

International campuses can go further, but perspectives would have to shift. To avoid privileging the head office, ditching the terminology of ‘branch’ campuses, would be a useful start. This would shift perceptions of them to platforms for engagement and collaboration in globally networked universities.

As ‘platforms’, they can become partners in the production of transnational curriculum (and research) that enriches the entire university, rather than just localising content for students in the so-called branch. And, as platforms, they can be active partners in processes of global quality assurance, instead of being framed as overseas risks that need to be carefully monitored.

Appropriately reimagined, international campuses can become nodes of collaborative engagement with universities, government, civil society and industry in their host countries. They can provide students with an educational experience that is simultaneously international and locally engaged. They can also serve as bridges to the first class institutions that have emerged in new higher-education landscapes.

The fundamental benefit of an international campus lies not in revenue (usually less than expected) or reputation (mixed). It lies in their potential to transform the DNA of the universities that establish them, orienting them towards global associations that fully explore the possibilities of a mutli-centric higher-education world.

Andrew Walker is Pro Vice-Chancellor and President of Monash University Malaysia.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.