Demand for higher education is hitting new heights in India, but the biggest beneficiaries seem to be foreign universities.

Sculpture at Karnatak University, Dharwad, India : Vijaya Narasimha

Sculpture at Karnatak University, Dharwad, India : Vijaya Narasimha

Demand for higher education is hitting new heights in India, but the biggest beneficiaries seem to be foreign universities.

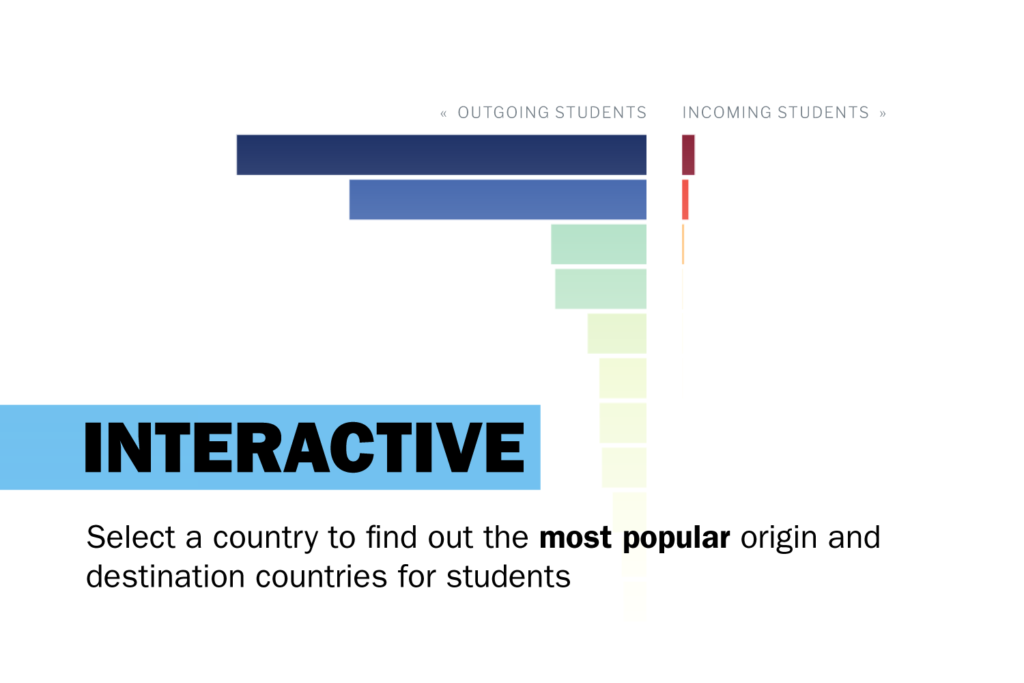

The number of Indian students seeking higher education abroad may increase to over 1.5 million by 2024, which is more than double the current number of students. The cost of their education will likely balloon from about US$26 billion to US$75 billion per year at the same time. Education is big business. But unless it invests, India will miss out on the opportunity.

In recent times, universities in developed countries found themselves charged with many new responsibilities. In addition to teaching and research, they were expected to provide skilled human resources for industrial growth, compete with each other for international rankings, and provide ideas and solutions for solving social problems. All this, with less public funding.

It is not surprising, therefore, that what started as a social-service enterprise has increasingly become a business.

The high cost of education is borne by foreign students. Attracted by the promise of higher-salaried job opportunities, better living standards and exposure to well-organised, high-quality education, more and more students and their parents make the considerable financial investment an offshore education requires. Students from developing, resource-poor countries such as India pay as much as triple the local fee for their study. Their fees subsidise the education of well-endowed students and universities in the developed world.

Yet the number of Indian students and their parents who are willing to pay an astronomically high cost for higher education has risen continuously over the years. Sensing a business opportunity, education brokers have sprung up to facilitate the process of application and placement of Indian students in foreign universities. There is good business all around.

Meanwhile, the developed countries grab the most talented, well-trained youth and benefit from their intellect, research and achievement — without having spent anything on their previous schooling.

Many of these students do not come back to India.

Given the heavy financial investment made by many students to study abroad, the higher-salaried jobs in developed economies — particularly in industries such as manufacturing and management — can help recover the money they have spent.

This suggests that if appropriate job opportunities are created, many more Indian students may return to work domestically.

Countries such as India would benefit from large investment in its higher-education system, filling the gap between supply and demand of quality higher education as well as creating appropriate job opportunities for its talented and trained labour force. Better future prospects and comfortable living standards will likely attract a larger pool of students to stay and work in India and serve society.

In some ways, the boom is already happening — it just needs more support.

At the time of independence from the British in 1947, India had about 20 universities and 200 colleges, with a total enrolment of only 120,000 students. Today, India boasts the second-largest higher-education system in the world, with an enrolment of nearly 40 million students.

With policymakers aiming to double the number of schoolchildren moving into higher education, this number could grow to more than 75 million students in the next few years.

The opportunity for higher-education growth and development is staring India in the face. The only question is whether the nation will seize it.

Virander S Chauhan is former chairman of the University Grants Commission of India and distinguished visiting professor, Institution of Eminence, University of Delhi. He declares no conflict of interest.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.