China: Preserving the local as universities become international

China’s universities have embraced a global perspective, but students say their own language, culture and history have been disregarded in the turn to the West.

For many Chinese students, the so-called ‘internationalisation of global education’ feels more like Westernisation: Ulrich and Mareli Aspeling, Unsplash.

For many Chinese students, the so-called ‘internationalisation of global education’ feels more like Westernisation: Ulrich and Mareli Aspeling, Unsplash.

China’s universities have embraced a global perspective, but students say their own language, culture and history have been disregarded in the turn to the West.

In universities throughout China international conferences are often conducted in English, even when most attendees are from China. This is just one of the many issues with higher education that Chinese students reported in a new study.

Many top Chinese universities have tried to become more international, recruiting professors from overseas, setting up study-abroad programs, adopting original English textbooks and using English as the language of instruction in courses.

Since China’s economic reform and opening up in 1978, the internationalisation of Chinese higher education has accelerated. The assumption is these practices will enhance the institutions’ reputations as world-class international universities.

The Chinese students who participated in the study are not against internationalisation, but they raise questions about its execution, suggesting that what is practised is more aptly termed ‘Westernisation’.

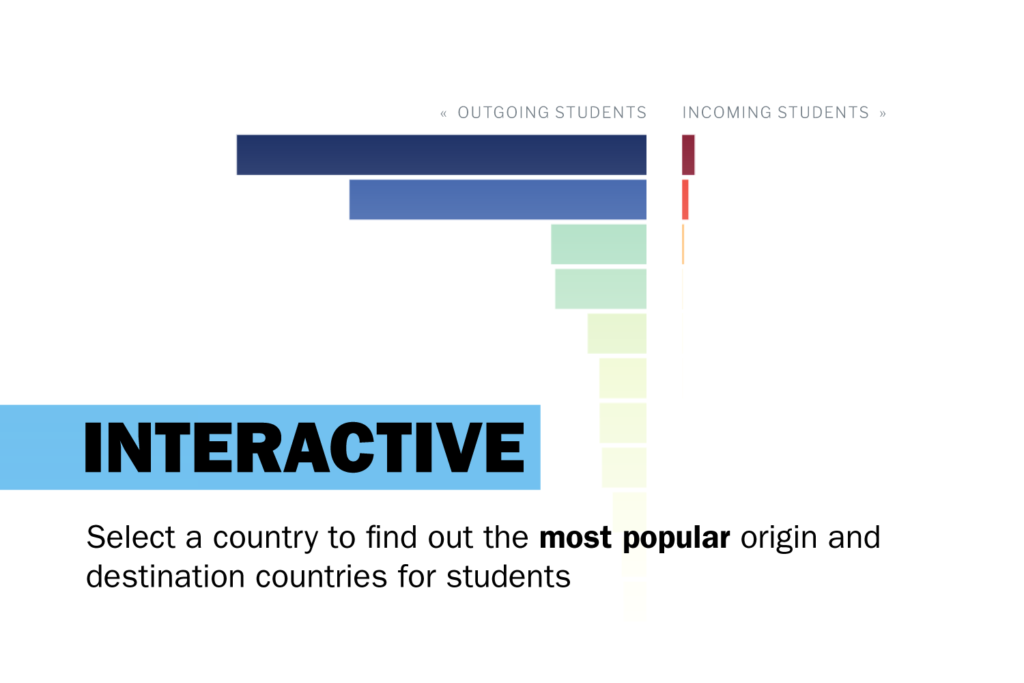

They took issue with the narrow perception of internationalised higher education: students were learning in and from a limited number of developed Western economies, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada.

The participating students were critical that Western sources of scholarship and knowledge were promoted as superior, whereas Chinese heritage and knowledge were seen as devalued.

From the students’ perspective, English has become a gatekeeper for internationalisation. As part of the informal curriculum, the English-language international conferences were seen as evidence of the narrow view of what it means to be international.

In the formal curriculum where ‘English as a medium of instruction’ (EMI) courses are taught as part of degree programs, students reported considerable difficulties in using English to understand the content due to their low proficiency with the language.

As one of the selection criteria for studying abroad, students needed high scores in International English Language Testing System or Test of English as a Foreign Language exams, which are international standardised measures of English language proficiency. These cost them time, effort and money.

Students were concerned that not all students have access to internationalisation. Only the economic and academic elite are likely to be selected for study-abroad programs. Rural students, without the financial resources and cultural capital of their more well-off peers, perceive studying overseas as impossible.

Where the narrow interpretation of ‘internationalisation’ of education speaks to the content and form of students’ experiences, concerns about inequality indicate the ways internationalisation is viewed in contemporary Chinese society.

Students’ lived experiences highlight tensions between internationalisation and localisation. Their accounts question the Eurocentric tendencies and the underlying colonial assumptions that influence the current ideological basis of internationalisation policies and practices.

In light of Chinese students’ perspectives and experiences, there is a need to de-Westernise the ideological underpinnings of higher education. As part of the de-Westernisation process, it is time for a rigorous examination of how Eurocentric assumptions embedded within internationalisation increases, rather than decreases, inequality in China.

Shibao Guo is a professor in the Werklund School of Education at the University of Calgary and a former president of the Comparative and International Education Society of Canada (CIESC). He can be reached at guos@ucalgary.ca. Prof Guo declared no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: In the story “Education brain drain” sent at: 11/04/2022 08:45.

This is a corrected repeat.