Developing nations in the Mekong have long had to choose between cheap, accessible power and sustainable river management. That may no longer be necessary.

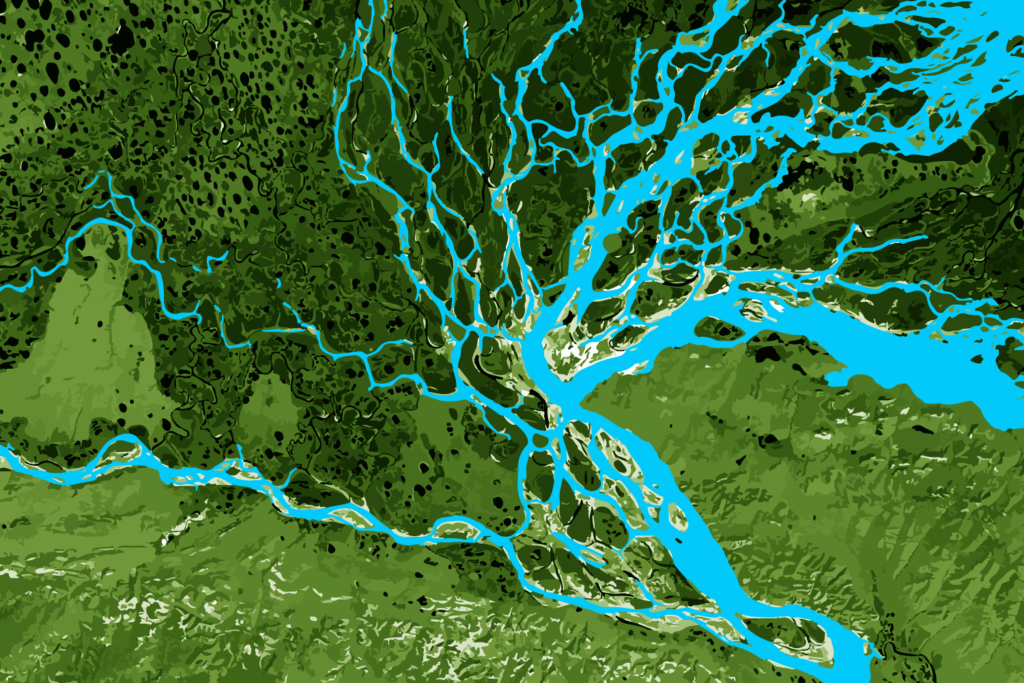

Vietnam’s Ya Ly Dam is one of many hydropower projects supplying cheaper, accessible energy — but at a cost to the Mekong River. (Tycho, Wikimedia Commons) : Tycho, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 4.0

Vietnam’s Ya Ly Dam is one of many hydropower projects supplying cheaper, accessible energy — but at a cost to the Mekong River. (Tycho, Wikimedia Commons) : Tycho, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 4.0

Developing nations in the Mekong have long had to choose between cheap, accessible power and sustainable river management. That may no longer be necessary.

Developing countries in the Mekong face a hard tradeoff. Their communities need more access to affordable energy for quality of life and economic growth, but they also need imminent action on climate change.

Many states have found a compromise in the Mekong’s large river basin and its untapped potential for hydropower — a source of carbon-free, cheap electricity. Stored in large dams, electricity is generated by using flowing water to spin a turbine connected to a power generator.

There are now over 90 hydropower dams in the lower basin alone. Not only does hydropower produce fewer CO2 emissions than fossil fuels, but the water used in electricity production is returned to the river afterwards.

However, dams alter and sometimes stop the natural flow—the lifeblood of rivers—and limit the transport of sediment and nutrients. Hydropower dams also impair the productivity of fisheries, disrupting or destroying the economies of local communities.

It has consistently been framed as a necessary tradeoff: developing nations could either have accessible electricity, or a healthy ecosystem, but not both.

New research has changed the equation. For developing Mekong states — Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia — tangible opportunities exist to meet future electricity demands and CO2 emissions targets, without requiring nearly as many hydropower dams as is currently planned.

The no-compromise solution is enabled in part by the decreasing cost of renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power. The Mekong has abundant photovoltaic potential, meaning it has the capacity to harness technology that can directly turn light into electricity.

Tapping into this could see businesses and investors switch from less environmentally sustainable developments such as hydropower.

Solar photovoltaic modules also have the advantage of being scalable and deployable in any province of the Greater Mekong region, meaning long-distance power transfers would cost less to implement.

Regionally coordinated power purchase agreements between countries are also helping make hydropower dams less necessary. Agreements to redistribute electricity among load centres help ease the individual burdens on each developing country, with wealthier nations incentivised to assist to preserve the Mekong’s ecosystem that all players benefit from. In supporting the integration of distributed generation resources, these partnerships help create a sustainable long-term power hub.

Taking on these actions should give states a range of options: they could pivot away from hydropower dams entirely, build only a fraction of what is planned or proceed with reduced construction. If states were to embrace a renewable energy-based solution, CO2 emissions targets could be met with up to 82 percent of planned dams still being built.

Any of the above approaches would help secure the Mekong’s river basin, a global hotspot of biodiversity, and would do so without having major implications on the price of electricity.

Even the most radical action, halting construction on all planned dams, is only expected to increase the costs of electricity infrastructure and production by an estimated 2.4 percent between now and 2037 (US$10 billion).

Developing countries in the Mekong region will continue to grapple with the challenge of making electricity accessible and affordable without destroying the surrounding ecosystem. For years, this has felt like a tragic tradeoff that states have had to consider.

The emergence of solar and wind technologies, and developing power market solutions, offer a set of options that helps states resolve, or at least address, the ecology/energy trade-off in a way that doesn’t feel binary.

This pathway forward is not only applicable to Mekong or Southeast Asia. Free-flowing rivers from South America to Sub-Saharan Africa are being dammed to help produce and provide electricity. New developments in the power market could end the energy compromise and usher in a more sustainable future.

Dr. Stefano Galelli graduated in Environmental Engineering at Politecnico di Milano in 2007 and received a Ph.D. in Information and Communication Technology from the same university in early 2011. He is currently an Associate Professor with the Engineering Systems and Design Pillar, Singapore University of Technology and Design.

Dr. Galelli declared no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

This research is supported by Singapore’s Ministry of Education (MoE) through the Tier 2 project “Linking water availability to hydropower supply—an engineering systems approach” (Award No. MOE2017-T2-1-143).

This article has been republished for World Rivers Day. It was first published on February 21, 2022.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: By Stefano Galelli in Singapore