This article was commissioned by 360info as part of a collaboration with Water Science Policy, including an interactive river journey of the Mekong. You can enjoy the full experience and learn more about this unique river here.

Chinese President Xi Jinping could influence the direction of the Mekong. (Presidential Executive Office of Russia, Wikimedia Commons) : Presidential Executive Office of Russia, Wikimedia Commons

Chinese President Xi Jinping could influence the direction of the Mekong. (Presidential Executive Office of Russia, Wikimedia Commons) : Presidential Executive Office of Russia, Wikimedia Commons

This article was commissioned by 360info as part of a collaboration with Water Science Policy, including an interactive river journey of the Mekong. You can enjoy the full experience and learn more about this unique river here.

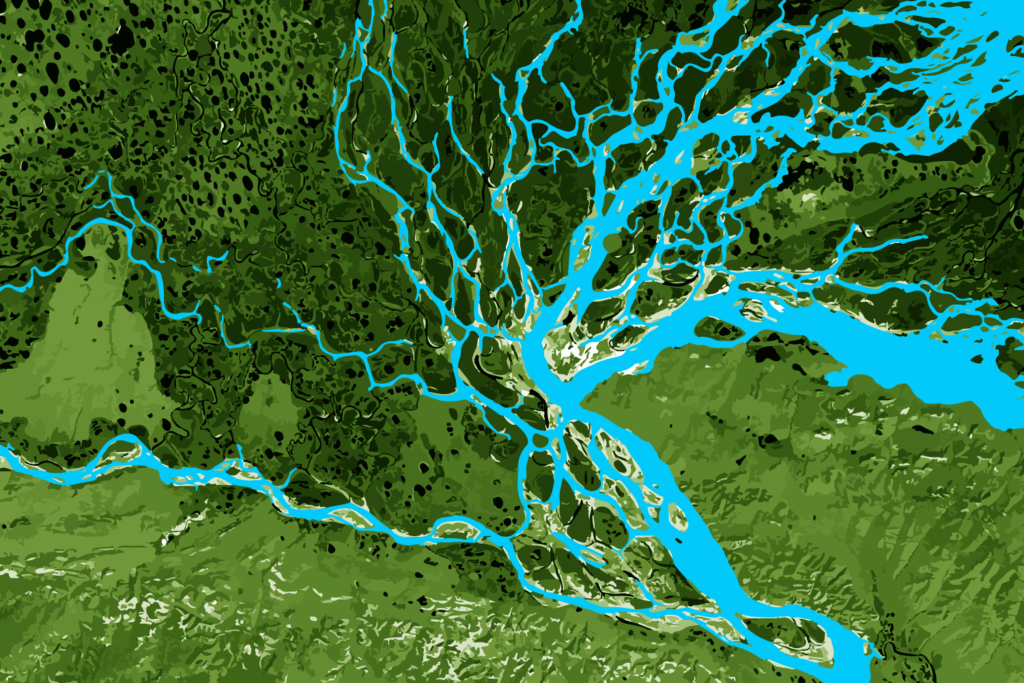

The success and survival of the Mekong River rests with China: the largest, wealthiest state in the region, positioned in the strategically important upstream. As the Mekong enters its fourth year of drought, certainty about China’s cooperation is no longer desirable — it is essential.

No institutional Mekong agreement simultaneously addresses transboundary effects, meaning Lower Mekong countries are dependent on the goodwill of China. China and Myanmar are the only countries in the region who are not member states of the Mekong River Commission, both are instead ‘dialogue partners’.

At times, China’s interest has aligned well with that of its neighbours. In 2016, it released emergency water supply from the Lancang River to tackle a drought in the Mekong. It is volunteering more data to the Mekong River Commission. China has also taken to, at times, notifying governments when it is set to reduce water flow of the river ahead of doing so in a goodwill gesture.

However, a framework built on ad hoc cooperation creates an uneasy situation for other Mekong states: China’s cooperation could cease at any point. Convincing China to become a member of a broader governance framework decreases the likelihood of China reversing the progress made in transboundary cooperation.

A powerful upstream country, China has little reason to deviate from current policy. There is little chance it will join the existing Mekong agreement or Commission any time soon.

Issue linkage could be a path to incentivise China to sign up a framework governing the Mekong waters, amongst other environmental areas — China could be compelled to participate more closely with regional partners on the Mekong through a transboundary environmental impact assessment, a holistic framework that includes — but is not limited to — the Mekong River and basin.

China is no stranger to issue linkage. By launching the Lancang-Mekong River Dialogue and Cooperation Mechanism, China successfully linked the issue of water governance to bring regional partners to the table on a raft of political and security issues. National environmental impact assessments vary vastly, not at least in terms of compatibility with China’s system.

The Lower Mekong countries have a streamlined environmental impact assessment process that follows similar principles and procedures. However, these lack any transboundary elements.

At the same time, there is a growing need for a transboundary impact assessment framework as larger projects in energy, water supply or traffic infrastructure increasingly have repercussions beyond individual states.

Lower Mekong countries could leverage issues that are in China’s interest, such as nuclear energy, to create a general transboundary framework. Recent cooperation agreements signed by Russia with Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam indicate nuclear energy might be a developing issue in the medium to long-term. Lower Mekong countries could also benefit from their pivotal role in China’s belt and road initiative (BRI).

So far, China’s envisioned ‘Green BRI’ depends on diplomacy and voluntary environmental commitment – which stands in stark contrast to environmental impact assessment rules within China. Since the dynamic economies of mainland southeast Asia are crucial to China, these states have leverage to claim a general need for a general transboundary environmental impact assessment framework.

An agreement of this nature would not be contradictory to Chinese interests. China’s President Xi Jinping’s concept of an ‘ecological civilisation’ (生态文明) draws an intrinsic link between environmental and commercial interests – and highlights the origin of environmental concerns in China’s own values and traditions.

A general framework for a transboundary environmental impact assessment would help increase the legitimacy for Chinese development in the Lower Mekong countries amid increasing resistance to its investment. Finding itself in competition with Japanese or Western companies when it comes to major infrastructure development, China is disadvantaged by growing scepticism.

Any attempt at creating a framework for a transboundary environmental impact assessment would have to bridge meaningfully diverging preferences, but there’s a blueprint to follow in the Espoo Convention, a transboundary agreement bridging parties in Europe, Central Asia and North America. The convention brings together diverse interests and countries, giving its parties some leeway on how their transboundary environmental impact assessments are conducted.

Institutionalised transboundary frameworks for environmental impact assessments are indispensable for sustainable governance of the Mekong river and basin, and beyond. Entrenching a more systematic approach to cooperating with China is in all parties’ interests.

Kenneth Stiller is a DPhil researcher at the University of Oxford. Kenneth holds a BA (distinction) in Political Science and Economics from the University of Mannheim, Germany and was an Adam-von-Trott scholar at the University of Oxford, where he obtained a master’s degree (distinction) in International Relations, focussing on political economy and quantitative methods.

Mr Stiller declared no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: Kenneth Stiller