A shift in perspective can future-proof the Indus Water Treaty.

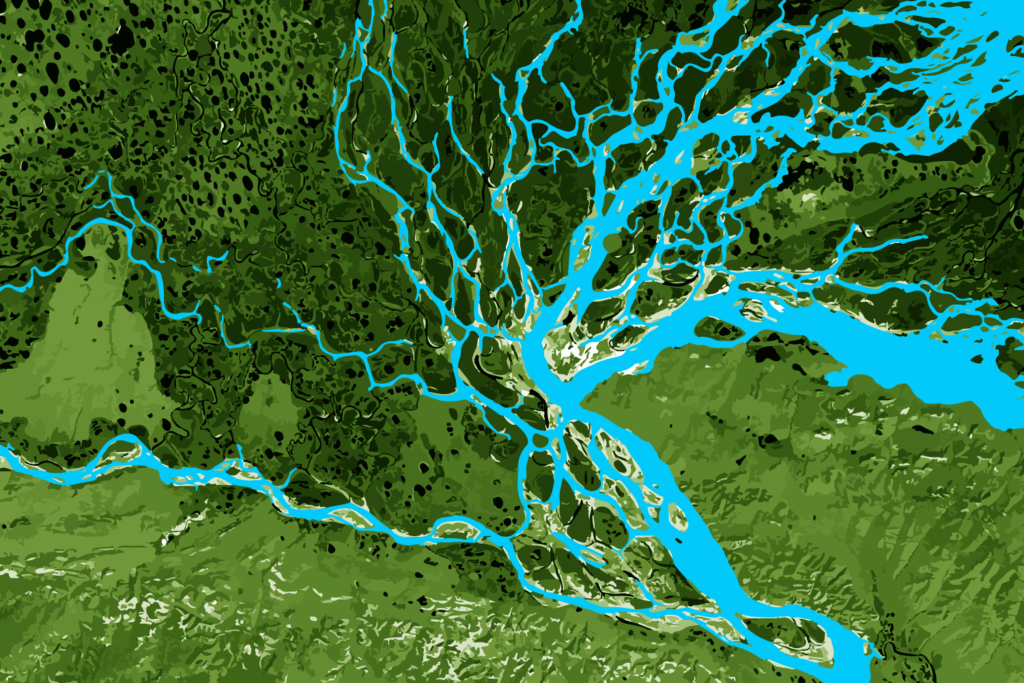

At the confluence of the Zanskar (middle) and Indus (left) rivers. : Ridhi D’Cruz/Wikimedia Commons CC SA 2.0

At the confluence of the Zanskar (middle) and Indus (left) rivers. : Ridhi D’Cruz/Wikimedia Commons CC SA 2.0

A shift in perspective can future-proof the Indus Water Treaty.

If they had known in the fifties what climate change would do to rivers, would India and Pakistan have signed the Indus Water Treaty? It’s this question the Indian government has triggered in the wake of its 12th report on water resources.

A re-negotiation of the Indus Water Treaty may be looming, following an August 2021 parliamentary report published by the Indian government. The Indian Commissioner for Indus Waters is planning to visit Pakistan in March to attend the annual meeting of the Permanent Indus Commission.

The report, prepared by the 12th standing committee, worries that climate change is largely ignored by the Treaty, which was agreed based on the knowledge and ‘technological imperatives’ available at the time it was negotiated, the 1950s.

These concerns, along with a recently-released report published by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), highlight a need for climate change adaptation. While the WMO report considers Integrated Water Resource Management a panacea for long-term wellbeing and security, it notes that many countries still remain off-track when it comes to the sustainable management of water resources.

The Treaty allocates the western rivers (Indus, Jhelum, Chenab) to Pakistan and the eastern rivers (Ravi, Beas, Sutlej) to India. But it has also granted India the right to certain non-consumptive uses of water on western rivers which includes generating hydroelectricity through run of the river dams, navigation and fishing, when certain conditions are met.

The focus on the Indus Basin is heavily tilted towards western rivers, where building hydrological structures is a priority concern for India. India has dismissed Pakistani reservations over dam development as a tactic to delay construction. When India and Pakistan have bilateral disputes over water, they have tended to revolve around hydro-power projects and rationing water. As a result, vital concerns such as water quality or nutrition security remain largely obfuscated.

The stakes are high: if the next major development in the Indus Water Treaty is mishandled, the worst-case scenario could see water conflicts between India and Pakistan become a pressing reality. However, if both countries can keep border claims aside and focus on joint development, a cooperative framework that adapts to contemporary issues can emerge. The challenge will be finding a way to facilitate this partnership.

From rationality to relationality

To achieve a stronger Indus Water Treaty, both states must shift from acting based on the rationality of water, and focus instead on its relationality. This means moving from water sharing (rationality) to benefit sharing (relationality). Rationality has a singular focus on volumetric allocation of water, and relationality expands the definition of water from surface water (water quantity), to water quality, preservation of wetlands and biodiversity, soil erosion, conjunctive use of ground and surface water, and nature based solutions. Doing so may help spur a different approach.

The rivers covered by the Treaty are diverse, flowing through different eco-climatic zones. The precipitation rates are different across the lower, middle and upper basins, some rivers are snow-fed, and the impacts of climate change are felt differently across the region.

The climate-related threats have been especially emphasised by Pakistan, international institutions and environmentalists. Such threats, dubbed ‘minimum environmental flows’, could reduce the flow of a river by 30-40 percent in future. The Indus Basin has faced a range of ecological issues, including siltation, water logging, the shifting of water tables, water contamination, groundwater extraction, flood management problems, and uncertainty over precipitation patterns.

These concerns are overlaid by changing demographics in India and Pakistan, increased urbanisation, and rising demands on the agricultural and industrial sectors. This has contributed to making both countries, particularly Pakistan, among the most water stressed in the world. Maintaining and ensuring environmental flows will be a tall challenge unless a compromise between water resource development and maintenance of the river is agreed.

In light of these concerns, a three-pronged approach that reframes the Indus Water Treaty through a relational lens may be most effective.

Leaders in India and Pakistan will need to shape a different approach, one that no longer sees water as an instrument for winning bargaining games. If they can’t, a trust deficit, water nationalism, and the securitisation of water could all contribute to escalating tensions, interstate and intrastate.

Both countries could also benefit from focusing more on a sub-basin level instead of managing the area with a singular holistic approach. Interventions at the sub-basin level that can account for contextual factors, such as the socio-economic composition of the area and the existing hydrology, would make the action more effective.

However, to truly bring the Indus Water Treaty into the present, its governance must be critically examined. The Treaty highlights many times the scope of cooperation and shared governance (in Articles 4, 5 and 7). Translating these words in the Treaty into more tangible action would greatly increase the bargaining range between India and Pakistan.

For example, Article 4 emphasises the use of communication channels regarding areas of concern across eastern and western rivers. It also tasks signatories with avoiding measures which cause direct or indirect harm to the other. Article 5 also outlines key areas that can foster cooperation between India and Pakistan, such as collaborating to prevent river erosion, promoting river protection, and treatment of sewage and industrial water at the source point. Article 7 utlines the possibility of optimum river development through a consultative data-sharing process for issues relating to drainage works.

A 2021 study found flood management, water quality, minimum environmental flows, exploitation of groundwater with the absence of a regulatory mechanism, were the primary concerns in Pakistan Punjab.

Alternatively, priorities which emerged from India were regulating the excessive exploitation of groundwater, reflection on cropping patterns, shifting water tables and shifting river course and water quality.

While these value preferences stemmed primarily from the Ravi sub-basin, they offer novel ways of approaching the Indus Water Treaty and Indus Basin in general. This not only necessitates alternative ways of undertaking suitable interventions to manage the Indus Basin, but also demands that a relational approach to the rivers and the ecosystem of the Indus Basin become a priority concern for both India and Pakistan. This will not only help us critically engage with what ‘water’ means, but also open up new pathways for benefit sharing mechanisms to future-proof the Indus Water Treaty.

Medha Bisht is senior assistant professor at the Department of International Relations at South Asian University, New Delhi. The author declared no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

This article has been republished for World Rivers Day. It was first published on February 21, 2022.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.