This article was commissioned by 360info as part of a collaboration with Water Science Policy, including an interactive river journey of the Mekong. You can enjoy the full experience and learn more about this unique river here.

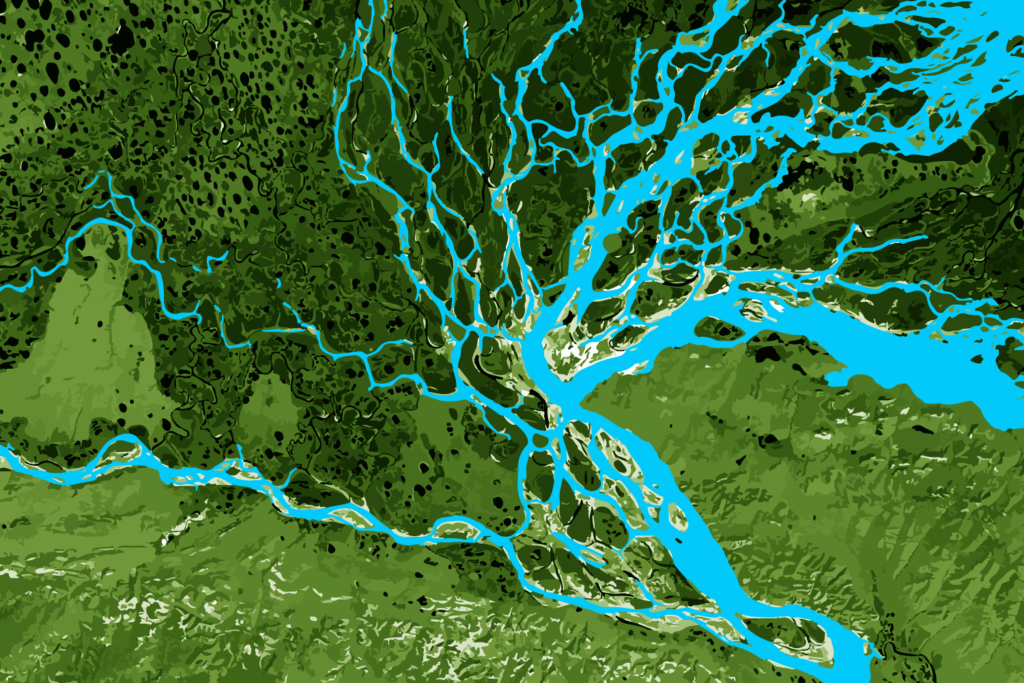

Saline intrusion is one of the environmental threats facing more than 70 million people who depend on the Mekong River. (Wandelende Tak, Wikimedia Commons) : Wandelende Tak, Wikimedia Commons

Saline intrusion is one of the environmental threats facing more than 70 million people who depend on the Mekong River. (Wandelende Tak, Wikimedia Commons) : Wandelende Tak, Wikimedia Commons

This article was commissioned by 360info as part of a collaboration with Water Science Policy, including an interactive river journey of the Mekong. You can enjoy the full experience and learn more about this unique river here.

Across parts of Bangkok, people woke up to tap water so salty that it was unsafe to drink in February 2021. The government was powerless to even dilute the saline water — coming off the heels of Thailand’s worst drought in 40 years, freshwater reserves were too scarce to be spared.

This is one of many examples of saline intrusions affecting states along the Mekong River. Low water discharge and low rainfall in the dry season results in backflow of saline water from the sea into the river, affecting agriculture, aquaculture, and livelihoods.

More than 70 million people depend on the Mekong River as a source of income and livelihood. Alongside saline intrusion, they face decreasing water levels and increased insecurity over water as the cumulative effects of climate change, dam development and environmental degradation set in.

While recent regional initiatives signify a push towards deeper engagement on the issue, the existential water security challenges in the Mekong-Lancang region are not being resolved fast enough to combat the damage being inflicted upon the region.

Soaring temperatures and volatile weather conditions are putting more pressure on dwindling water supplies in almost all Southeast Asian countries. Long-term forecasts predict more severe droughts in the future, risking further saline intrusion.

In Vietnam, the Mekong usually turns salty only for about a month each year. In recent years, farmers have dealt with salinity for at least four months at a time, a consequence of upstream dams, sand mining and climate change discharging lower amounts of freshwater into the delta. High salinity in the soil makes it impossible for crops and produce to survive, creating huge losses for farmers in the region.

Given that the majority of the southeast Asian region rely on agricultural production for their livelihoods, drought and water insecurity have a major impact on their lives.

On 12 November 2020, ASEAN member states adopted the first Declaration on the Strengthening of Adaptation to Drought. The declaration calls for substantial action, aimed at enhancing drought adaptation and mitigation capabilities in the region, as well as promoting a longer-term, more strategic approach towards drought management.

ASEAN launched a comprehensive regional plan of action on adaptation to drought on 14 October 2021. The plan seeks to find a sustainable way to manage droughts, preventing and mitigating its impacts on livelihoods, natural resources, the ecosystem, agriculture, energy and socio-economic development.

ASEAN hopes that these two documents will build coordination among the group and effectively address the impacts of drought. To deal with water security challenges in the Mekong, ASEAN has also formally engaged with the Mekong River Commission (MRC).

People with a stake in the Mekong have been collaborating to address water scarcity, water pollution, and other water-related disaster risks. They could learn from Singapore.

The Singapore Government’s Four National Taps strategy (local catchment, imported water, Newater, desalinated water) has helped the country build a robust, diversified, and sustainable supply of water despite the country’s high population density and lack of natural water resources.

Working with partners outside the region is also another potential way to tackle water insecurity. ASEAN can work towards fostering better ties with other regional blocs like the Pacific Islands Forum.

Southeast Asian states have a lot in common with Pacific Island states in terms of geographical and economic vulnerabilities. They all have a vested interest in addressing water security issues.

Christopher Chen is an Associate Research Fellow with the Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) Programme, Centre for Non-Traditional Security (NTS) Studies at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. Christopher declared no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: In the story “Water conflict” sent at: 21/02/2022 09:33.

This is a corrected repeat.