As technology improves, satellite-imagery based applications could help deliver faster humanitarian responses.

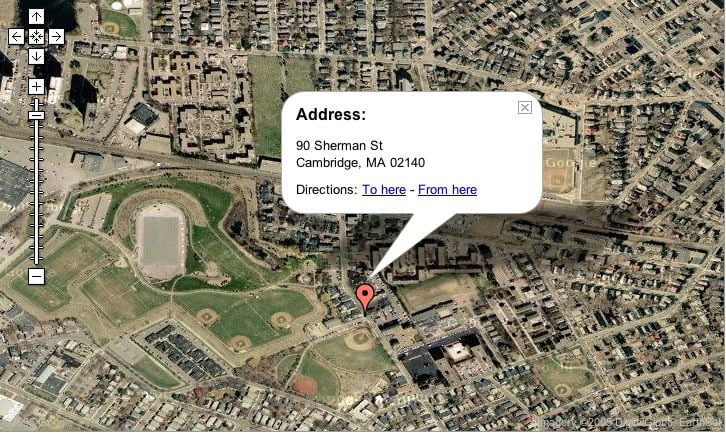

Satellite image of a refugee camp taken in 2016. : Planet Labs, Inc. Wikimedia Commons.

Satellite image of a refugee camp taken in 2016. : Planet Labs, Inc. Wikimedia Commons.

As technology improves, satellite-imagery based applications could help deliver faster humanitarian responses.

For any humanitarian crisis, the key to responding is “to target aid to the right people at the right place at the right time”. But collecting information on refugees (or in more general terms, forcibly displaced people), can be difficult. Access can be limited and safety concerns high, eroding crucial time to help those who are fleeing conflict.

Satellite imagery can help humanitarian operations by providing immediate information on the location, number of people, the situation and environment surrounding them to help with logistics and planning.

At the end of 2020, 82.4 million people were forcibly displaced due to persecution, conflict, violence, or human rights violations, with around 86 percent of them from countries with developing economies. They struggle with a lot of challenges such as a lack of food, nutrition, clean water, sanitation, and difficult access to education or medical services. To map out how much aid is required, up-to-date and high-quality data creates a set of visual representations of what refugee dwellings look like — the building ‘footprint’ — which can help estimate the size of the population in need. However, the building footprints, especially in remote areas, are often outdated or not available in open source data such as OpenStreetMap.

Updated very high spatial resolution satellite imagery such as Pléiades and WorldVie, are effective in estimating the number of people displaced. Taking images of the footprints across time can also help in monitoring the growth and dismantling of temporary refugee shelters.

Experts have developed different approaches for the use of satellite imagery in extracting refugee dwellings and estimating displaced people. Up to now, manually delineating and checking using Geographic Information System software by experienced staff can produce the highest-accuracy dwelling footprints. However, it is tedious, time-consuming and labour-intensive because there are usually tens of thousands of dwellings to be delineated.

Instead, using a semi-automated approach — what’s known as geographical object-based image analysis (OBIA) — has become popular in humanitarian operations in the last decade. The core of OBIA is to design rulesets to help the computer recognise dwellings automatically. For example, these might be areas larger than 40 square metres, rectangle shapes, bluish roof colour. However, designing these rulesets requires expert knowledge and they are usually complex as the shelters are different across various regions or periods.

With the fast development of AI technology, deep-learning based approaches have become increasingly popular in extracting refugee dwellings. This allows computers to learn what a dwelling looks like from training data, with the computer developing its own criteria by which to recognise them. Produced refugee dwelling footprints from historical humanitarian operations based on OBIA have high potential to be used as training data for deep learning models.

Updated information of land cover and land use near refugee camps can also help us understand the potential supply of crucial natural resources for daily survival such as water, firewood and building materials. Satellite imagery and auxiliary data from multiple sources can assist the exploration of underground water near refugee camps so that bores might be sunk. It uses medium-resolution satellite imagery (such as the United-States based Landsat program, and the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer) and radar imagery to map different types of rock that is visible on the surface.

This information is then combined with Digital Elevation Models (3D computer graphics representation of elevation data to represent terrain) to find the location of groundwater. Just as satellite imagery can help direct humanitarian aid, it can also detect the environmental impact of refugees.

Monitoring changes in the environment surrounding refugee camps, such as removal of trees, water sources and a change in the built environment, is a significant indicator of depletion of natural resources for host countries.

The Rohingya people in Rakhine State, Myanmar, have suffered from discrimination, statelessness and targeted violence over the decades. As of March of 2019, over 900,000 Rohingya people have been forcibly displaced to Ukhiya and Teknaf Upazilas in Bangladesh. Researchers used Landsat-5 TM and Landsat-8 OLI TIRS imagery to categorise land use near Rohingya refugee camps. They analysed the area every ten years from 1990 to 2020 to assess the environmental change and found that in agricultural land, settlements, and where refugee camps have increased, the bodies of water, sandy land and vegetation have declined.

Satellite imagery can assist in identifying areas at risk of an outbreak of potential infectious diseases, particularly vector-borne diseases like malaria. It can also help in assessing the risks of natural disasters near refugee camps, which can wreak havoc on already unstable housing structures.

Information extracted from multi-source satellite imagery has proved to be beneficial for humanitarian operations. However, higher speed and higher accuracy are still required. With the fast development of satellite sensors, AI technology, and the benefit of past experiences, satellite-imagery based applications have high potential for faster humanitarian responses by providing more accurate and essential information for logistics planning and risk assessments.

Yunya Gao is a researcher at the Christian Doppler Laboratory for geospatial and EO-based humanitarian technologies (GEOHUM) at the Department of Geoinformatics – Z_GIS, of the Paris Lodron University of Salzburg.

This research has received funding support from the Austrian Federal Ministry for Digital and Economic Affairs, the National Foundation for Research, Technology and Development, the Christian Doppler Research Association (CDG), and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Austria.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.