Artificial intelligence offers new possibilities to states assessing visa applications, bringing new urgency to the need for international standards.

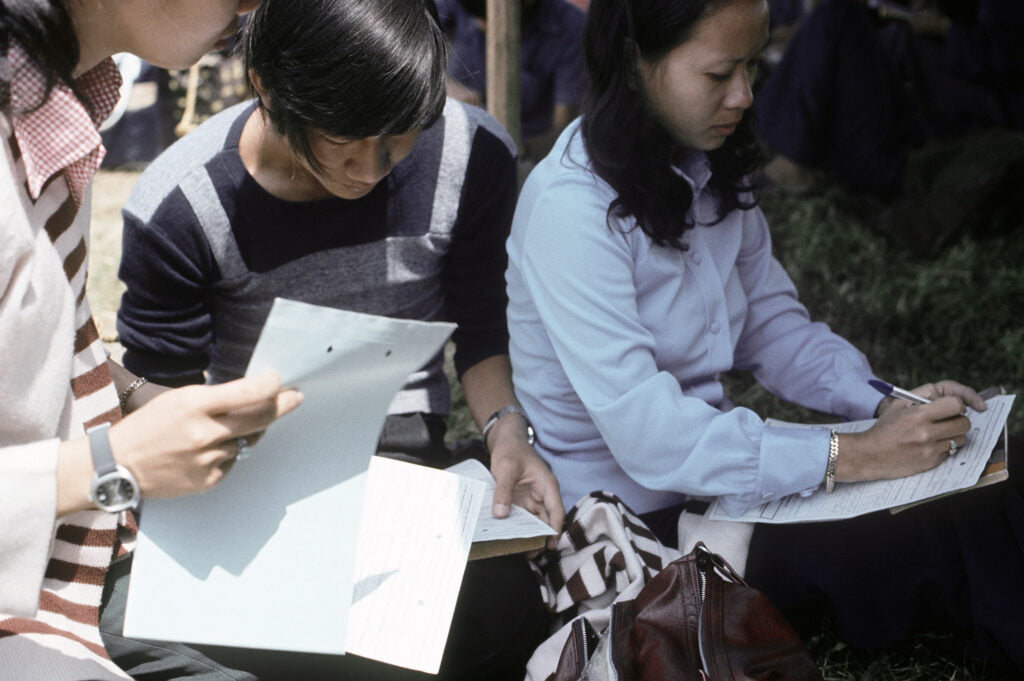

The US has put a stop to paper forms for some noncitizen visitors. : Manhhai/Flickr CC BY 2.0

The US has put a stop to paper forms for some noncitizen visitors. : Manhhai/Flickr CC BY 2.0

Artificial intelligence offers new possibilities to states assessing visa applications, bringing new urgency to the need for international standards.

Algorithms, artificial intelligence and machine learning have permeated our daily lives, delivering new conveniences, and new threats to our privacy.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the treatment of the personal data of migrants. The data once collected on forms and filed away is now immediately digitised — just last month the US put a stop to paper forms for noncitizen visitors travelling under its popular visa waiver program.

The alternative ESTA form, online and fairly inexpensive, has become longer and longer as more questions have been added to it over the years. Each additional question is designed to reveal more about the personal behaviour of the individual, such as the destinations of previous travel or immigration records elsewhere. And it’s a trend repeated in more and more countries, including in the European Union as it establishes its own travel authorisation system.

The personal data requested for these forms is far more than what would normally have been collected where a tourist presented him or herself at a border without the pre-authorisation procedure.

International standards are now needed to ensure migrants are not the object of unjustifiable data grabs by states, whether they’re travelling for tourism or other reasons.

People agree to give up their personal data because they want to travel. Those who want to move for a longer period usually have to obtain visas which require substantially more personal data not only about them and their family members, but also sensitive information such as income, assets and tax returns. While citizens are generally protected from intrusive data questioning when entering their own state because they have a right to enter, foreigners have no such shield. If they refuse to hand over their personal data to the authorities they will not be able to travel.

In the past, this data was filed manually or electronically in a file specific to the individual and was rarely consulted except in exceptional circumstances. But the development of new AI and machine learning technologies has provided state authorities with a whole new set of possibilities.

Data collected for border and immigration purposes is being used for multiple purposes, not all of which are consistent with the reasons for which the data was first collected. Nor are the uses necessarily benign. State authorities are taking decisions and discriminating on the basis of flawed profiles.

In 2020 a report by the UK’s Independent Chief Inspector of Borders found authorities were using an AI tool to classify visit visa applications of nationals of certain countries according to profiles which they had developed: GREEN (to be approved), YELLOW (to be reviewed) and RED (recommended for refusal). But the tool resulted in what has been described as racist decision making: assumptions built into the profiles resulted in prejudice in the assessment of applications. When challenged in the courts, the UK government decided to withdraw the use of the tool rather than to try to defend its use before a judge.

In the private sector, data brokers face regulation of their data collection under national and international measures. But when the authority collecting personal data is the state and the purposes are opaque not only do national constitutional protections come into play but their applicability to migrants becomes critical.

States remain hungry for intrusive information about individuals ostensibly for the purposes of protecting national security. International standards are needed to ensure they’re not more likely to drive discriminatory practices than stymie real threats.

Elspeth Guild is a law professor at Queen mary university of London. She is also a practising lawyer at Kingsley Napley London. The author declares no conflict of interest.

This article is part of a Special Report on the ‘Changing face of migration’, produced in collaboration with the Calcutta Research Group.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.