Poverty and abuse often mean Indian girls and women see human traffickers as their ticket to a better life – and this only grew worse during the pandemic.

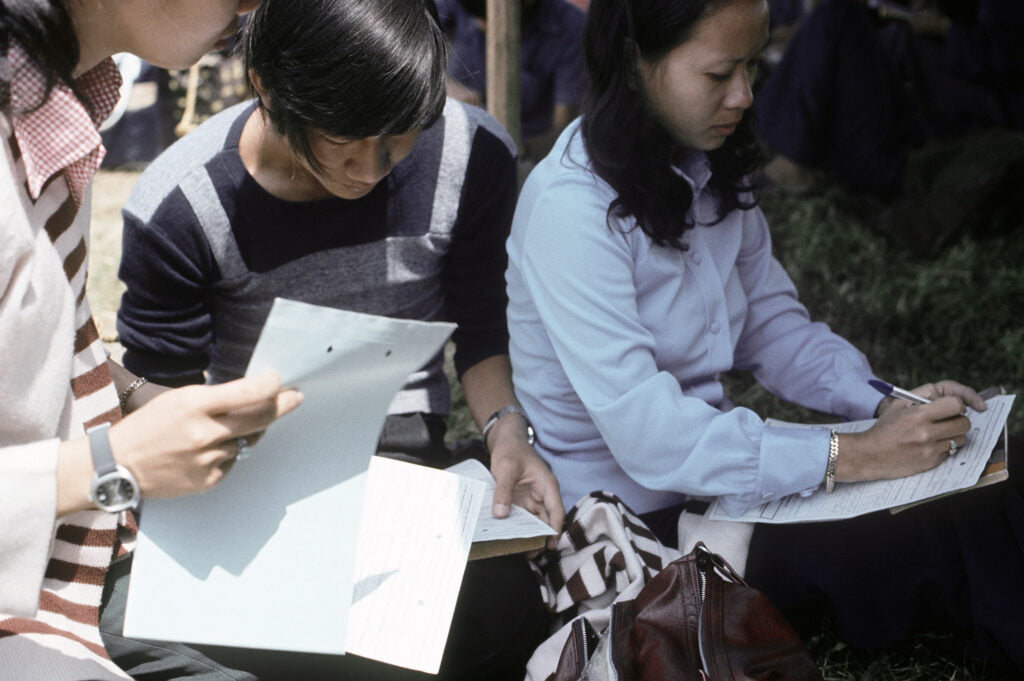

Vulnerable girls in India received none of the benefits of their citizenship rights and so they do not fear losing those rights. : Abhisek Sarda, Flickr (https://bit.ly/3HwtuzW) CC BY 2.0

Vulnerable girls in India received none of the benefits of their citizenship rights and so they do not fear losing those rights. : Abhisek Sarda, Flickr (https://bit.ly/3HwtuzW) CC BY 2.0

Poverty and abuse often mean Indian girls and women see human traffickers as their ticket to a better life – and this only grew worse during the pandemic.

Nearly 230 million Indians have fallen below the poverty line since the COVID-19 pandemic began. And it’s a sad fact that vulnerable, desperate people attract predators. Between April 2020 and June 2021, more than 9000 children were rescued from human traffickers. Strict pandemic lockdowns followed by the devastation of cyclone Amphan in coastal Bengal in 2020 left girls highly vulnerable to traffickers.

But there is more to the story: Indian girls and women often have few rights and protections even before they are trafficked. Experts say they frequently see trafficking as their way out of poverty and into a life of at least some agency.

The poverty-stricken Sundarban areas of Bengal, where cyclone Amphan hit hardest, have become hot spots for trafficking in women and girls, according to a report in The Hindu. Cut off from legal aid because of damaged road and telecommunications infrastructure, these areas have seen an alarming spike in human trafficking.

West Bengal’s tea-plantation areas, such as New Jalpaiguri and Darjeeling, are also highly vulnerable to trafficking. Due to the pandemic lockdowns the plantation workers were practically living without food and began sending their children out to work as cheap labourers.

A Bengali television channel reported district police had noticed most minor girls trafficked from tea gardens in the last two years had been found in Bengal’s red-light districts. On 30 January 2022 police held awareness camps for tea-garden workers so they knew where they were sending their children and what kind of work they were getting in the cities.

Baitali Ganguly is the founder and director of Jabala, which provides support to the children of sex workers and also works on safe migration of girls particularly from plantation areas of Alipurduar. Speaking to researchers in Kolkata in June 2022, Baitali refused to accept the narrative of victimhood in relation to increased trafficking of girls from the plantations.

She said “it is wrong to think the girls were unaware of the issues related to trafficking. They submit to the traffickers because for them the traffickers are not predators but a path to a world where they can escape their poverty and live their lives to the full”.

For many of them this is their conscious choice. That is why even when they are apprehended by police they do not accuse their traffickers or make them responsible for their legal situation.

As many as 16 million of India’s 20 million commercial prostitutes are victims of sex trafficking, according to a 2017 Reuters report. Traffickers are rarely prosecuted and are punished even more rarely. In a 2018 case, two Indian brothel owners – a husband-and-wife team from Gaya in eastern India – were jailed for life after four of their child victims, rescued in a police raid in 2015, took the stand against them. But this case was a first.

Writing about the outcome, journalist Anuradha Nagaraja quoted Indian government data showing, ‘less than half of the more than 8,000 human trafficking cases reported in 2016 were filed in court by the police and the conviction rate in cases that did go to trial was 28 percent’. International reports by the United Nations and other agencies frequently note this underground aspect of trafficking.

Identifying victims of trafficking is difficult even under normal circumstances, but COVID-19 is ‘making the task of identifying victims of human trafficking even more difficult’ according to a recent UN Office on Drugs and Crime report. Experts say poverty in the post-pandemic period is likely to drive many more young girls and women into the hands of traffickers. Worse, the pandemic ‘caused governments to divert resources away from anti-trafficking efforts’.

During COVID-19 women and girls in poorer areas in India suffered violence from immediate family members in much greater numbers than in the pre-pandemic days. The state is obliged to protect them, but it responded only with enormous apathy. Vulnerable girls grew sicker and lived through unthinkable abuse. They got none of the benefits of their citizenship rights and so they do not fear losing those rights. Unless the state and civil society safeguard the rights of girls and women, work to reduce poverty and make migration safe for female workers, the evils of trafficking cannot be addressed.

Paula Banerjee is a Professor and Head of the Department at the University of Calcutta. She is a senior researcher in Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group, an avant garde think tank on Migration and Forced Migration Studies. She is known for her work on Gender, Border and Migration.

No conflicts of interest were delcared in relation to this article.

This article is part of a Special Report on the ‘Changing face of migration’, produced in collaboration with the Calcutta Research Group. It was first published in June 2022.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: In the story “Migration’s changing face” sent at: 17/06/2022 12:58.

This is a corrected repeat.