Although trade unions are widespread in China, conditions for rural-to-urban migrant workers haven’t improved as fast as they have for local urban employees.

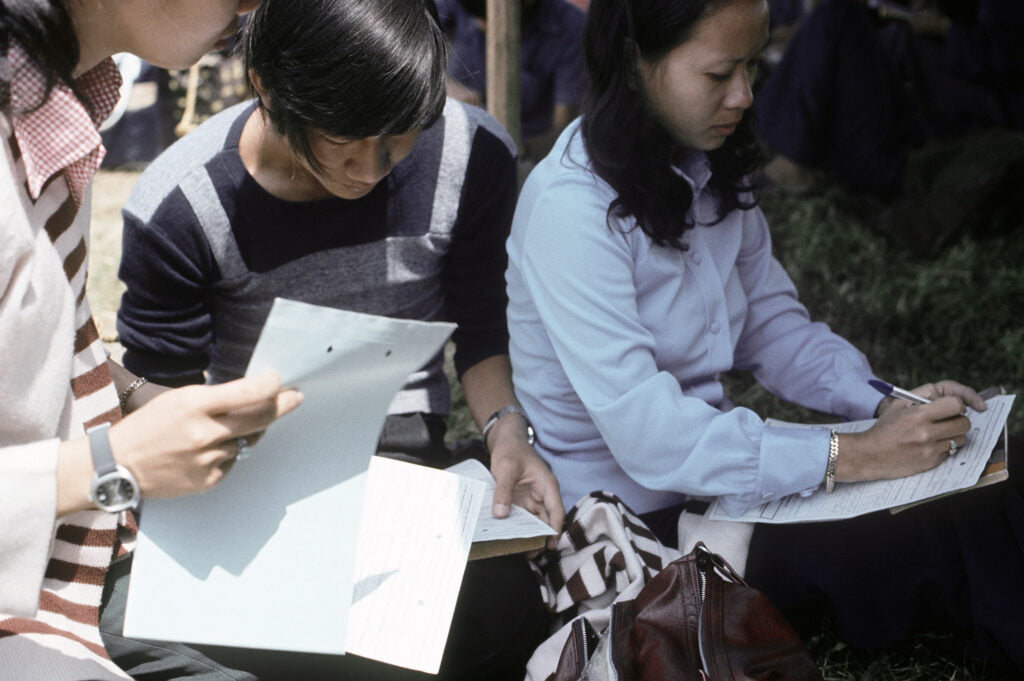

While trade unions are widespread across China, rural-to-urban workers particularly suffer when their union is an inactive ‘paper union’. : Tauno Tõhk, Flickr CC BY 2.0 (https://bit.ly/3mXoOJQ

While trade unions are widespread across China, rural-to-urban workers particularly suffer when their union is an inactive ‘paper union’. : Tauno Tõhk, Flickr CC BY 2.0 (https://bit.ly/3mXoOJQ

Although trade unions are widespread in China, conditions for rural-to-urban migrant workers haven’t improved as fast as they have for local urban employees.

China’s rapid urban transformation led to vast numbers of new jobs offering better pay than rural work. People migrated from villages to secure these jobs and try to lift their families’ standard of living. In 2019, 36 percent of China’s working population – an estimated 291 million people – were rural-to-urban migrant labourers. But despite China’s nation-wide network of trade unions and reforms intended to protect rural-to-urban migrants, exploitation persists. Fighting it may require a rethink of government monitoring and enforcement efforts.

As early as the 1990s, violations of Chinese internal migrant workers’ basic rights had been widely reported, putting pressure on regulators to protect these rights. Legal reforms required workplaces and firms to establish their own trade unions to help workers bargain for their labour conditions. While for some this resulted in active protection, other workplaces established ‘paper unions’: unions that don’t engage in collective activities to protect workers’ rights.

Rural-to-urban workers are often treated as second-class citizens in cities — they often occupy “3-D” jobs, referring to positions that are dirty, dangerous and demeaning; and local city dwellers often hold social stigmatisation and distrust against those of rural origins, believing the latter to be poorly educated, occupationally incapable and socially liable. This grants urban natives privilege and consolidates their status at the expense of those coming from villages.

Migrant workers are continually discriminated against in the urban labour market. They are asked to work long hours and to take up dangerous jobs, and they are laid off without compensation. Unemployment has a particularly significant impact on the mental health of migrant workers.

Alone, migrant workers lack leverage and power, but union members could bargain with firms for meaningful change, starting with increased hourly pay, reduced working hours and secure social-insurance protections. It is well established that higher hourly pay and more leisure time boost workers’ wellbeing, whereas working more than eight hours a day threatens their mental health.

Both the state and local governments intervene in cases of labour violations. Presently, local governments in China often receive multiple, sometimes conflicting orders from upper-level units, resulting in confusion when local governments attempt to implement public policies.

A restructure of China’s government units could fortify the chain of command, ensuring all lower-level governments receive clear guidelines on forming policies. This would aid efforts to prevent and sanction workplace exploitation of Chinese migrant workers, such as monitoring local trade unions to ensure more union members are active in organising or participating in activities to protect their rights.

With labour protections already in place, simply encouraging compliance by working units should benefit migrant workers. Workplaces with active trade unions already seem to operate quite well: wage arrears are substantially lower in such firms that also offer permanent or long-term labour contracts (one year or more), and workers there are more likely to be covered by welfare provisions, including a housing fund.

Rural-to-urban migrant labourers are an indispensable part of China’s workforce. Legal reforms implemented over decades have put into place all the functions required to give workers a world-class standard of protection, but administrative mismanagement and a willingness to ignore paper unions are undermining the health and wellbeing of migrant workers.

Jason Hung is a Global Health PhD Fellow at the United Nations University – International Institute for Global Health (UNU-IIGH).

No conflicts of interest were delcared in relation to this article.

This article is part of a Special Report on the ‘Changing face of migration’, produced in collaboration with the Calcutta Research Group. It was first published in June 2022.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.