Cities cannot function without domestic workers in India but their employment conditions remain precarious.

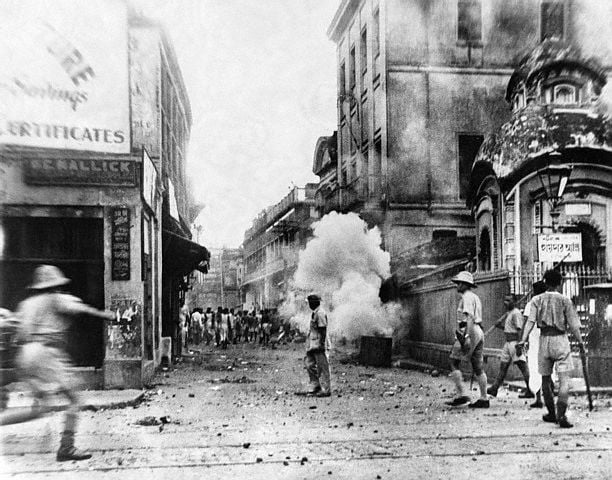

Women are more likely to be employed as domestic workers in India where pay and job security are precarious. : Prayudi Hartono via Flickr CCBY2.0

Women are more likely to be employed as domestic workers in India where pay and job security are precarious. : Prayudi Hartono via Flickr CCBY2.0

Cities cannot function without domestic workers in India but their employment conditions remain precarious.

Domestic workers are the third-largest category of workers after agriculture and construction in India. They form a significant part of the total workforce in the informal sector in India. An overwhelming majority of them are women.

The employment fragility of domestic workers has been often brought out in the media. Their wages are entirely self-negotiated and dependent on the employer’s goodwill. Without the protection of legally-binding contracts or legislated agreements, they cannot afford to fall sick for fear of losing their jobs and being replaced.

In Kolkata, a domestic worker can work on full-time or part-time basis, may be employed by a single household or by multiple households, may be residing in the household of the employer (live-in worker) or may be living in her or his own residence (live-out). A vast majority of them are migrant workers. These domestic workers were engaged in cooking, cleaning, driving, looking after elders and children, care work in sickness and in health and other household services for remuneration.

It is a precarious living and it took a pandemic to reveal just how much. Lower wages and less secure working conditions have become the norm since COVID-19.

The suffering of female domestic workers during the pandemic revealed their insecure working conditions. Jargi Orao, a domestic worker in her 50s from Chhattisgarh found employment in a genteel household in Kolkata’s Salt Lake area. Her situation was particularly good as her employer was a woman who took good care of her. Jargi had one married son and an unmarried daughter, who was mentally unstable and living in an institution.

Her problems started with the lockdown. The asylum where her daughter was staying forced some patients to return home. Since Jargi’s daughter did not have a home of her own, her brother brought her to their mother. But when Jargi requested her employer to let her daughter stay, she was summarily dismissed.

Having lost her job during the lockdown, she had to go back to her son’s home in the Dum Dum slum where seven people were forced to live in one room. Because of the loss of income, Jargi was forced to live off her meagre savings, which led to further insecurity.

Jotsna Naskar, from the South 24 Pargana district, worked as domestic help in the Shaktigarh area of Jadavpur before the pandemic. She worked in five households and earned 6,000-7,000 rupees per month.

After the lockdown on 20 March 2020, suburban train services were stopped and all transport from villages to the city was disrupted. “I came to collect my salary in the last week of April,” she said. “I went to the houses where I worked. Some of the apartments did not even allow me to enter the premises. Some of them had given me the salary of March and then said not to come ’til the (COVID-19) vaccine became available in the market.”

Another domestic worker, mother-of-two Purnima Paik, 35, lived in Kolaghat village in the South 24 Pargana district.

“We had good income and our economic condition before lockdown was good,” she said. “I used to earn 7,000-8,000 rupees per month. My husband’s earnings were also particularly good. Now, the wages have become very low in the agricultural sector.

“I lost my job where I worked for several years as domestic help. Some of the families were not willing to allow anyone into their houses. They are especially afraid of us as we commute by train every day. Now many of the households are seeking people who can stay for 24 hours in their houses and are ready to pay more for that. But I cannot as I have to take care of my own children and have to do my own household work. ”

The International Labour Organization places the number of domestic workers in India at 4.75 million, (of which 3 million are women). However, this is considered a severe underestimation and the real number could be anywhere between 20 million to 80 million.

One reason why women make up an overwhelming number of domestic workers is this kind of work is seen as an extension of their gender roles. In a cruel twist, they are paid less than men in the same sector. In India, women make up 8.8 per cent of the total registered workforce, underlining how important domestic workers are in urban India.

According to the World Bank the Female Worker Population Ratio in Bengal has risen steadily but the state has lagged historically compared with the rest of India. In 2020, the ratio in Bengal was 23.1 percent while the national average was 28.7 percent. Most of this increase has been in urban areas. Between 1991 and 2001 women’s work participation rate doubled in Kolkata from 6.91 percent to 12.84 percent.

While middle class women sought jobs in the city, their homes were being looked after by domestic workers. However, the increase in numbers did not prove to be an improvement in standards of living.

In November 2022, the state government of West Bengal agreed to consider the demands of Paschim Banga Griha Paricharika Samiti and decide on a minimum wage for domestic workers. Although this is a move in the right direction, the question remains how that will help domestic workers, particularly female domestic workers. Without laws that enforces employers to register their domestic workers these women will remain irregular workers and outside the reach of any legislation.

Paula Bannerjee is the convener, Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Calcutta and editor of Refugee Watch. She is a former Vice-Chancellor of The Sanskrit College and University and has been dean of Arts, University of Calcutta, a former president IASFM and director of MCRG and Foreign Policy Studies.

This article is part of a Special Report on ‘Cities after colonialism’, produced in collaboration with the Calcutta Research Group.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.