Depoliticised planning in Dhaka has meant a shift away from professional planners and public concerns.

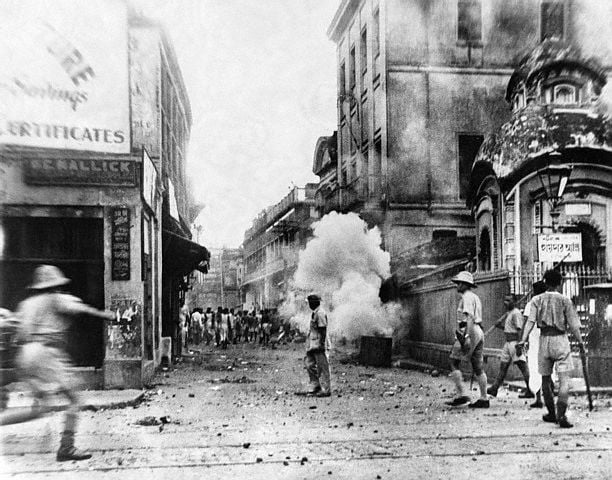

Dhaka’s urban planning system is synonymous with a cumbersome bureaucracy, procedural inefficiency and lack of public accountability. : Pinu Rahman CC4.0

Dhaka’s urban planning system is synonymous with a cumbersome bureaucracy, procedural inefficiency and lack of public accountability. : Pinu Rahman CC4.0

Depoliticised planning in Dhaka has meant a shift away from professional planners and public concerns.

Bangladesh’s capital Dhaka is the 11th largest and the fastest-growing megacity in the world and faces an acute liveability and sustainability crisis.

The city is home to 18 million people and despite socio-economic, cultural vibrancy and a rich natural environment, unprecedented population growth, climate-change effects, economic growth imperatives and poor institutional capacity have challenged planners and policy makers to deliver liveability and sustainability outcomes. The city has become chaotic and socially iniquitous, its natural environment destroyed.

Like many other parts of the Global South, Dhaka’s urban planning has been historically controlled by the colonial and post-colonial regimes with minimal public input. As technical experts, planners cannot even fulfil their roles except as lip service to higher authorities. In Dhaka’s urban planning, professional planners are not major players.

Liveability and sustainability are contested concepts and linked in ways that must be understood in any planning initiative. While liveability is present and local, sustainability is a long-term and global phenomenon. These differences in scale account for the tension between the ‘local and the immediate’ and the ‘global and the long-term’. Liveability and sustainability planning for a city thus creates power and political tensions among various groups with conflicting priorities.

Dhaka’s planning process is being shaped by poverty reduction, economic growth and modernisation dictated by the political, bureaucratic and technical elites, along with the private interests of powerful forces. This elite group uses their administrative as well as formal and informal political power to influence planning decisions and implementation. This has shifted decision making away from planners to others such as a cabinet committee, donors, the military, police and developers, who all have competing interests.

Although Dhaka’s more recent planning documents attempted to address liveability and sustainability issues, translating them into practice is not straightforward. The western modernisation and neoliberal city ideals held by different elites of Dhaka are at odds with the city’s planning practices mainly due to its status as a developing country’s capital, as well as poor institutional capacity and democratic immaturity.

This, in turn, gives rise to a complex post-political condition, a ‘depoliticisation’ process which seeks to exclude contentious political relations created by the lack of democratic participation combined with neoliberal thinking held by the elites. It suppresses planning experts in particular, and democratic participation generally. Although international donor agencies impose governance changes to some extent, planning in many developing cities of the Global South, including Dhaka, is still state-led and centralised.

Dhaka’s urban planning system is thus synonymous with a cumbersome bureaucracy, procedural inefficiency and lack of public accountability.

In the Transport and Wetlands planning cases, planning in Dhaka seems dominated by urban political elites (cabinet committee, ministers); bureaucratic elites (top officials of ministries and planning authorities); technical elites (engineers of relevant state agencies); professional elites (the military and police in the wetlands case); business elites (real estate leaders in the wetlands case); and economic elites (international donor agencies in the transport case).

These elites exercise power to ensure their own interests influence planning decisions. State elites force planning authorities to engage selected professional civil society bodies (Bangladesh Institute of Planners, Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association, Bangladesh Poribesh Andolon) to legitimise decisions. But planners in general have little scope to consider recommendations from professional groups or go by their own sustainability rationales. The government elites shift planning power away from the planning institutions and planners.

In the colonial period, planning ideas and practices, including master plans for cities and urban modernisation, were transferred from Europe to the colonial cities of the global South. Dhaka was no exception.

It inherited its bureaucratic organisational framework from the British Colonial Government via the Pakistani regime (of which Bangladesh was a part as East Pakistan before independence). However, independent Bangladesh continues to maintain this structure in its planning and land-use activities. The master planning tool has failed to control messy urbanisation and maintain a planned development of Dhaka.

Findings from the transport planning practice (through interviews with planners/practitioners and documents analysis), showed that despite planners’ intentions and planning recommendations for active modes of transport, improved public buses, railways and waterways, only modern mega road projects such as elevated expressways, metro rail and flyovers received attention.

The underlying rationale for mega-projects rests on mobility, economic growth, poverty reduction and urban modernisation. On top of that, politicians think such projects are their achievement and use them in election campaigns. While large-scale metropolitan transport projects in Dhaka improve current liveability benefits from economic growth and mobility, this trend largely ignores localised sustainable transportation and creates tensions for both present and future generations concerning liveability and sustainability.

Similarly, the efforts of planners in conserving Dhaka’s wetlands are often disregarded by interest groups motivated by economic growth, modernisation and private benefits. The outcome is the continuous decline of wetlands leading to waterlogging, flooding, waterborne diseases and biodiversity loss from water pollution.

An important outcome is also an increase in social inequity ⎯ a serious concern for current liveability and future sustainability. Overall, urban planning and practices do not, and cannot, manage the twin challenges of liveability and sustainability in the city.

Tareq Zahirul Haque is a PhD Candidate (Teaching and Research Sessional), School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia.

This article is part of a Special Report on ‘Cities after colonialism’, produced in collaboration with the Calcutta Research Group.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.