Unsafe and disaster-prone, extractive towns are still attractive to migrant workers.

Picking at the seams of mines becomes the only way to eke out a living for many people in the coal mining towns of West Bengal. : Nit1994 CC4.0

Picking at the seams of mines becomes the only way to eke out a living for many people in the coal mining towns of West Bengal. : Nit1994 CC4.0

Unsafe and disaster-prone, extractive towns are still attractive to migrant workers.

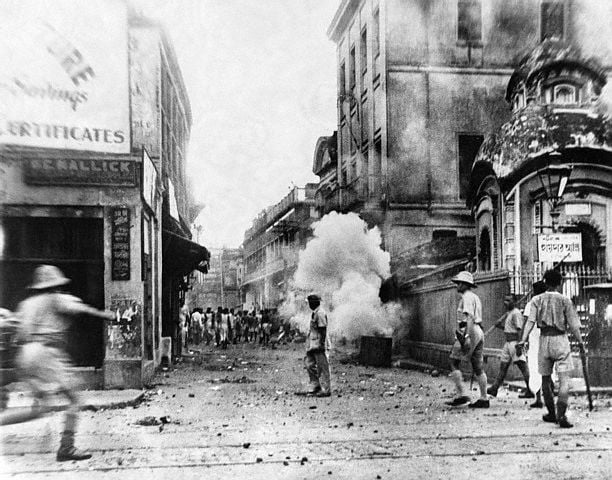

The coalfields around Asansol, 210km northwest of Kolkata in West Bengal have provided a way of life for workers since colonial times. But for the thousands drawn to the area for job opportunities, those same mines also carry the risk of death.

Along with the prosperity coal has brought for mining companies comes pollution, shaft collapses and displacement.

These problems have continued since the 19th century when indiscriminate extraction and unscientific methods of mining led to land-subsidence, mine fires, air, water and land pollution, displacement and mining related health issues.

Yet the promise of employment, housing, water, transport, healthcare centres and schools acted as a magnet and these towns continued to draw people to the coalfields and subsequent mines digging for other mineral reserves such as iron ore, manganese and bauxite.

Asansol owes its development to the growth of coal mines, but its sustainability as an extractive town now faces ecological limits while other mining towns in the area face a long battle ahead to become environmentally liveable and sustainable.

Coal mining represented the new modern economy of Bengal under which the region flourished during colonial times. The region, in the Raniganj Coalfield of West Bengal, at the fringe of the Chota Nagpur Plateau in Eastern India, has been a hub of commercial coal production since 1840.

Asansol, then a railway hub, became the focus for the growth in the coal producing region and supported Kolkata as a secondary enclave and home to migrant workers. Mining practices have been haphazard, unplanned and unscientific.

As a result, the urban centres in the coal region are threatened by unstable ground and land subsidence. Safety concerns for collieries, towns and surrounding areas only surfaced since the nationalisation of coal mines in India in the 1970s.

Environmental measures and subsidence control schemes were outlined in a 2009 Master Plan. Land use development now falls under the remit of the Asansol Durgapur Development Authority which works closely with Eastern Coalfields Limited and the Central Mine Planning and Design Institute Limited Regional Institute in Asansol.

Though the government, mining company and development authority sometimes address the issues of subsidence and mine fires, it is difficult to implement checks and controls at every mine site.

The hunger for coal means once-productive farmland is swallowed up by mines. Open-cast mines operate near residential areas on the city boundary. Despite the risks, displaced people still encroach into the peripheral areas of mines to scavenge coal.

As mining companies buy up more land, there is less for farming. Other areas near mines become unproductive. Land acquisition contracts do not always proceed as planned, triggering loss of livelihood, worse employment conditions and reduced incomes.

Development projects such as the construction of dams, industrial townships, expansion of coal mines and growth of infrastructure and transport projects have displaced more than 100,000 people since the 1950s. Land loss and the failure to adapt to alternative livelihoods at times cause distress migration.

The Sonepur-Bazari open-cast mine area has been a prominent zone of displacement. Travelling this urban industrial corridor, you see people on bicycles with overflowing bags of coal collected from the fringes pits. With farming jobs disappearing, picking at the seams of abandoned mines becomes the only way to eke out a living.

Urban sprawl to the edge of mines leads to safety concerns. However, as mining is the impetus for economic growth, towns around the coalfield continue to grow, causing a subsequent demand for more land.

And migrant workers continue to come despite poorer contractual arrangements and fewer social protections due to outsourcing. Allied industries such as iron pigment and ingot manufacturing plants, refractories and brick kilns also provide possibilities of employment.

As Asansol confronts the pressures of urban sprawl toward open pit pines, safety issues and pollution — among the worst in India — land development needs to be more attuned to the hazards.

Reforestation, stricter control of mine operations, greater safety efforts, accessibility to water and transport services all need a greater focus to reduce regional imbalances.

Shatabdi Das is a researcher with the Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata.

This article is part of a Special Report on ‘Cities after colonialism’, produced in collaboration with the Calcutta Research Group.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.