Cities in South and Southeast Asia share many characteristics and can learn from each other’s history, development trajectories and experiences.

Thailand’s capital Bangkok was part of self-colonialism though it’s never been colonised. : “River View of Wat Arun in Bangkok” by Marco Verch is available at https://bit.ly/3FDpwEY CC by 2.0

Thailand’s capital Bangkok was part of self-colonialism though it’s never been colonised. : “River View of Wat Arun in Bangkok” by Marco Verch is available at https://bit.ly/3FDpwEY CC by 2.0

Cities in South and Southeast Asia share many characteristics and can learn from each other’s history, development trajectories and experiences.

There is an irony in many Asian nations that after the colonisers were kicked out the ruling elites inherited, sustained and continued to impose colonial governance and practices upon their nascent nation-states. This extended to the modernisation and economic development of their countries and cities; to become ‘high-income’ and ‘developed’. This is unsurprising as the elite mind was/is concurrently colonised and self-colonised.

Take ‘self-colonisation’. In the 19th-20th centuries the rulers of Siam (Thailand) and Persia (Iran) tried to avoid direct European colonisation. But their capitals, Bangkok and Tehran, developed with European urban planning practices anyway. Many European specialists were employed in these self-colonisation and modernisation projects which were later expanded through the training and educating of the locals.

While the indigenous application and extension of colonial practices resulted in hybrid forms and practices more adapted to local conditions, the tradition of sending and educating generations of leaders in Western institutions only served to entrench self-colonisation. That mindset and associated self-imagery was imposed upon their home city from top-down policies and development to the personal spaces of everyday life.

A long-term consequence of this phenomenon in tropical Southeast Asia is the shared ‘climatic self-colonisation’ where the middle and upper classes exists segregated from the rest 24/7 in the air-conditioned spaces of their bedroom, private car (or expanding modern rail public transport), to their workspace (offices) and recreational space (shopping malls).

Further reinforcing this divide, the city has been formally planned for this segment of society based on desirable images and practices of cities in developed countries (Europe, the US, Japan and South Korea) that, in effect, leave large swathes of the city ‘unplanned’.

Crucially, this imposed segregation reflects the continued colonial prejudice towards and the suppression of indigenous identities and practices – captured in the sustained and evolved bottom-up practices of ‘indigenous modernity’. This is modernisation as interpreted and appropriated by the masses and manifests in a parallel city that evolved responsive to its climatic, socio-economic and cultural characteristics.

It is encapsulated in the ‘informal’ practices of the pervasive ‘village in the city’ typology (e.g. kampung settlements that encompass old communities and newer squatter settlements) and street commerce of many Southeast Asian cities. They are characterised by low-rise, high-density living and working where the blurring of public and private spaces, close personal proximity are conducive to establishing trust and socio-economic relationships (social capital).

While it isn’t possible to revert to traditional ways and many aspects of very high-density living are problematic and unhealthy, there are relevant lessons for city planners and administrators – whether for small-scale incremental retrofits or rebuilding the existing fabric, or rebuilding whole cities. The practice of indigenous modernity often emerges from necessity and consensus and embraces a decolonising mindset. It can be temporary or sustained across generations by necessity or by choice.

However, the de-colonising challenge is culture-deep and respective Southeast Asian societies habitually look outwards for development models rather than reflectively inwards and/or to each other.

The founding of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) serves as a collective political frame for the region’s decolonisation that orients the cultural gaze away from the former colonisers and back to the region and to each other’s shared heritage, developmental status and trajectories.

The rise of smartphones, social media and advances in translation apps enable virtual dialogues between individuals that transcend language barriers. While such interactions can exaggerate differences and exacerbate existing conflicts, more meaningful connections are also formed.

ASEAN travel and work visa agreements have led to increased intra-ASEAN travel that, by extension, promote cross-cultural understandings and the potential emergence of a co-designed cultural-awareness policy and education (comparable to those of the European Commission).

Shifts in Western education institutions in their awareness and accommodation of the Global South content is also critical. Decolonisation needs to occur in the Global South and North to effectively reduce ignorance and prejudice and enhance understanding for students, who are the future change-makers in the region.

This is crucial in the context of the multiple challenges from climate change and biodiversity loss that require new connections and collaborations to interrogate how we live in the city to mitigate for and reverse the depletion of our natural resources.

Indigenous modernity offers Southeast Asian cities bottom-up alternatives to self-colonisation and homogeneous modernisation. It provides lessons and possibilities on how societies can move on from their colonial past to become genuinely post-colonial. If city administrators and stakeholders engage with and creatively harness their indigenous modernity, it can serve as a decolonising framework towards a more inclusive, sustainable city.

Sidh Sintusingha is Landscape Architecture Program Coordinator at the Melbourne School of Design. He researches on socio-cultural, environmental and scalar issues relating to urbanisation and the speculation of retrofits towards urban sustainability in Southeast Asian cities. He recently co-edited a book on bottom-up country experiences of the Belt and Road Initiatives and co-authored an article in Journal of Urban Design with Ross King, “Nationalism and urban design: the parliament houses of Canberra and Bangkok.”

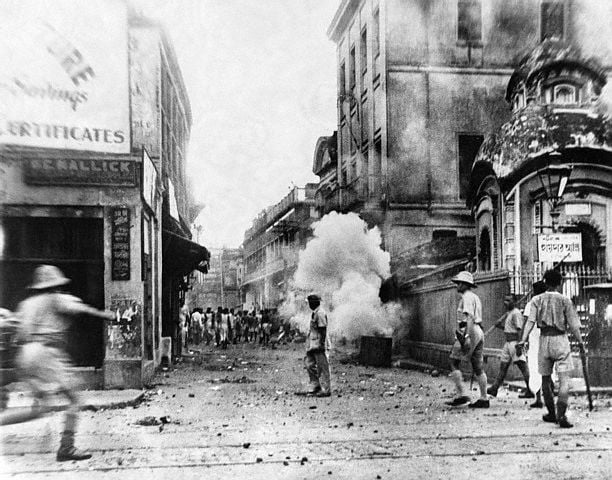

This article is part of a Special Report on ‘Cities after colonialism’, produced in collaboration with the Calcutta Research Group.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: Sidh Sintusingh – public services