Capital punishment has fewer practitioners than ever before, but the momentum of the abolitionist movement may be halted by some committed to the death penalty.

Although many countries have abolished the death penalty, 55 nations maintain capital punishment with some especially committed to executions. : Francesca Runza, Unsplash CC BY 4.0

Although many countries have abolished the death penalty, 55 nations maintain capital punishment with some especially committed to executions. : Francesca Runza, Unsplash CC BY 4.0

Capital punishment has fewer practitioners than ever before, but the momentum of the abolitionist movement may be halted by some committed to the death penalty.

Capital punishment itself is dying, but its demise is slow.

In assessing 2021, Amnesty International declared “more than two-thirds of the countries in the world have now abolished the death penalty in law or practice” — that’s 108 countries that have dropped the death penalty outright, eight which maintain it for extraordinary circumstances, and 28 that are abolitionist in practice (having “not executed anyone during the last 10 years or more and are believed to have a policy or established practice of not carrying out executions”).

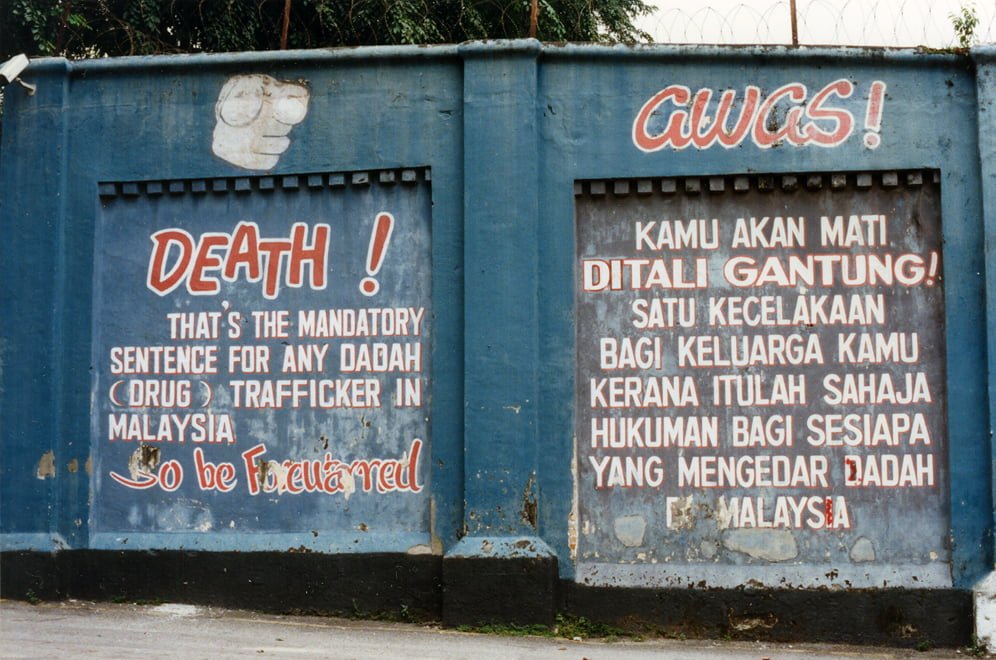

That leaves 55 countries where the death penalty is still in use for ordinary crimes, but even the number of convicted criminals executed annually is in decline.

Of the countries remaining, there are are a dozen or so who seem particularly fixed on the death penalty — 18 countries executed people in 2021 and, among them, 11 have been persistently doing so since 2017: China, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Sudan, Vietnam, Yemen, and the US. Excluding the thousand-plus killed by the “world’s leading executioner” China, whose death penalty data is classified as a state secret, 80 percent of the 579 known executions last year were conducted in Iran, Egypt and Saudi Arabia. These countries pose a stern roadblock for the abolitionist trend, and threaten to snuff out hopes of a global end to the death penalty happening any time soon.

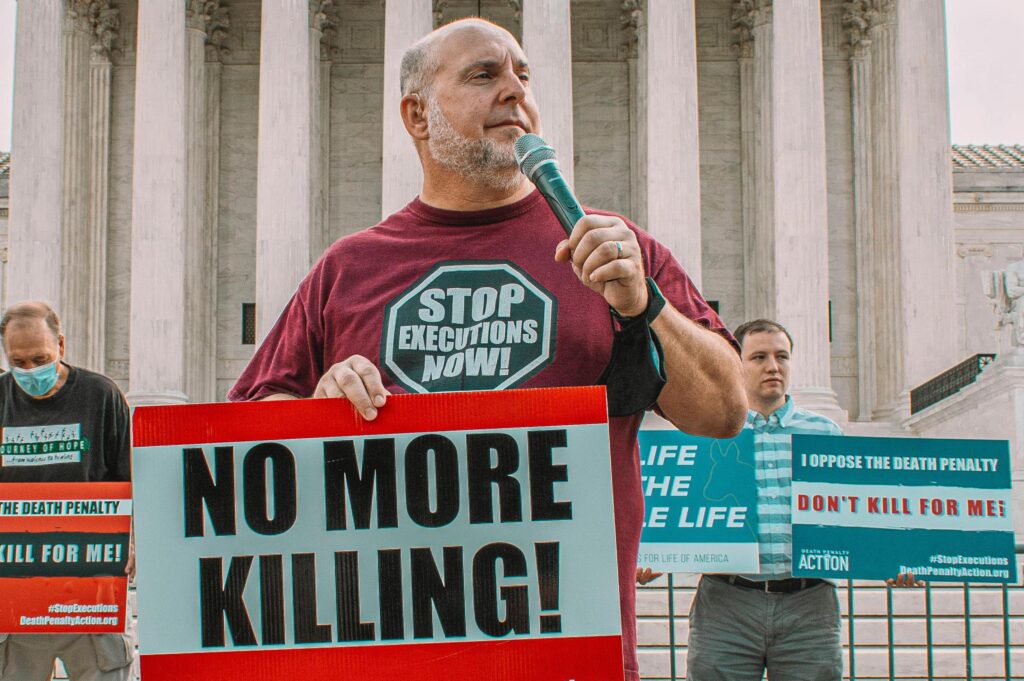

However, taking lessons from countries that have done away withthe death penalty, there are some key indicators showing how a country can effectively move past capital punishment without total and catastrophic upheaval.

Democracy and democratisation are said to be major political factors driving the abolition of the death penalty. Indeed, the global abolitionist trend has progressed hand in hand with the waves of democratisation in countries in Latin America in the 1980s and in the former Soviet bloc in the 1990s, during which a number of countries abolished the death penalty.

For a government in transition, the abolition of the death penalty serves as a symbolic departure from the former authoritarian regime, which grossly abused human rights and used the death penalty for political repression or persecution. It is also expected to enhance its legitimacy domestically and internationally. The fact is, of the above-listed 11 countries persistently conducting executions, at least eight countries are regarded as authoritarian regimes. However, the relationship between the death penalty and democracy is not fully clearcut, as we can see from the cases of the democratic United States and Japan — the former executed 11 people and the latter three people in 2021.

Political turmoil seems to have more direct impact on states’ resort to the death penalty. Of the 11 countries raised above, Somalia and Yemen have each been locked in civil war, and Iraq and South Sudan have been gripped by political unrest and violence between communities. These countries, except for Iraq, have seen a noticeable increase in recorded executions in 2021. Syria also reportedly executed at least 24 people in 2021. In Syria, Somalia, and Yemen, death sentences were often imposed for alleged acts of terrorism or treason.

The death penalty has been widely used by governments to repress protesters and minorities. Iran, which has already executed more than 250 people since January 2022, has been using death sentences disproportionately against ethnic minorities as a tool of political repression. In Myanmar, use of the death penalty has spiked following the military coup in February 2021, becoming “a tool for the military in the ongoing and widespread persecution, intimidating and harassment of and violence on protesters and journalists”. At least 86 people were sentenced to death in Myanmar in 2021, a huge jump from the yearly average of less than 10 in years prior. Last month the military executed four democratic activists for the first time since 1988.

If countries aren’t yet prepared to do away with the death penalty, it may be more palatable to reserve its use for exceptional circumstances. Strictly speaking, international law does not directly outlaw the death penalty but restricts its use to “the most serious crimes” and in ways that would not violate international law and standards. The most serious crimes include the very limited cases allowed under the United Nations’ Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ratified by 80 countries), such as retaining the death penalty in time of war (if they make such reservation at time of ratification). This allowed the UK, for instance, to maintain capital punishment for treason until 1998.

Although this is viable under international law, the concept of an “enemy of the state” is easily and arbitrarily defined by governments, often in order to judicially abuse the death penalty. A Russian proxy court in eastern Ukraine sentenced two Britons and a Moroccan to death in June 2022 over charges of being mercenaries. The UK government and Ukraine’s foreign ministry called the sentences an “egregious breach” of the Geneva Conventions, which set out legal humanitarian standards for times of war. Russia introduced a moratorium on executions in 1996 and is regarded as abolitionist in practice, but in issuing death sentences — and possibly doing so again if they try Ukrainian prisoners of war in Mariupol — an abolitionist country may slide back into practicing capital punishment.

But abolitionism is about more than ending executions. 2021 saw historically low recorded executions, but also at least 2052 new death sentences were imposed in 56 countries — a 39 percent increase from the year prior. The gap between executions and death sentences means there is a huge number of inmates sitting on death row, waiting for executions. By the end of 2021, there were at least 28,670 people worldwide believed to be under a death sentence — and that’s without adequate data from China, Egypt, Iran, North Korea and Saudi Arabia.

And of those tens of thousands, a vast majority live in concerning conditions. In Japan, for instance, those on death row are given notification of their execution only hours in advance. It means they may spend years in solitary confinement with the threat of imminent death looming over their heads without respite.

Death penalty policies do not exist in a vacuum. They reflect how governments conceive of criminal punishment, which is closely related to their attitude to human rights, governance, order and justice.

Governments that are experiencing volatility, instability or unrest tend to find it more challenging to exercise control over those areas, and under such situations, are more prone to putting the death penalty in practice for arbitrary or political purposes. As the abolitionist movement tries to win over the remaining third of capital punishment countries, advocates may benefit from a diverse and multi-faceted consideration of how and why countries exercise this most extreme form of punishment.

Madoka Futamura is Professor at the Department of Sociology, Hosei University. She specialises in International Peace and Security and International Criminal Justice.

Prof Futamura disclosed no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.