As Indonesia moves to shed its colonial, undemocratic past, its so-called ‘moderate’ death penalty laws — riddled with ambiguity — undermines any move forward.

Indonesia is reforming its criminal justice system but still faces many challenges. : Ichigo121212/Pixabay CC by 2.0 Ichigo121212

Indonesia is reforming its criminal justice system but still faces many challenges. : Ichigo121212/Pixabay CC by 2.0 Ichigo121212

As Indonesia moves to shed its colonial, undemocratic past, its so-called ‘moderate’ death penalty laws — riddled with ambiguity — undermines any move forward.

Indonesia is on the cusp of the biggest criminal justice reform since independence.

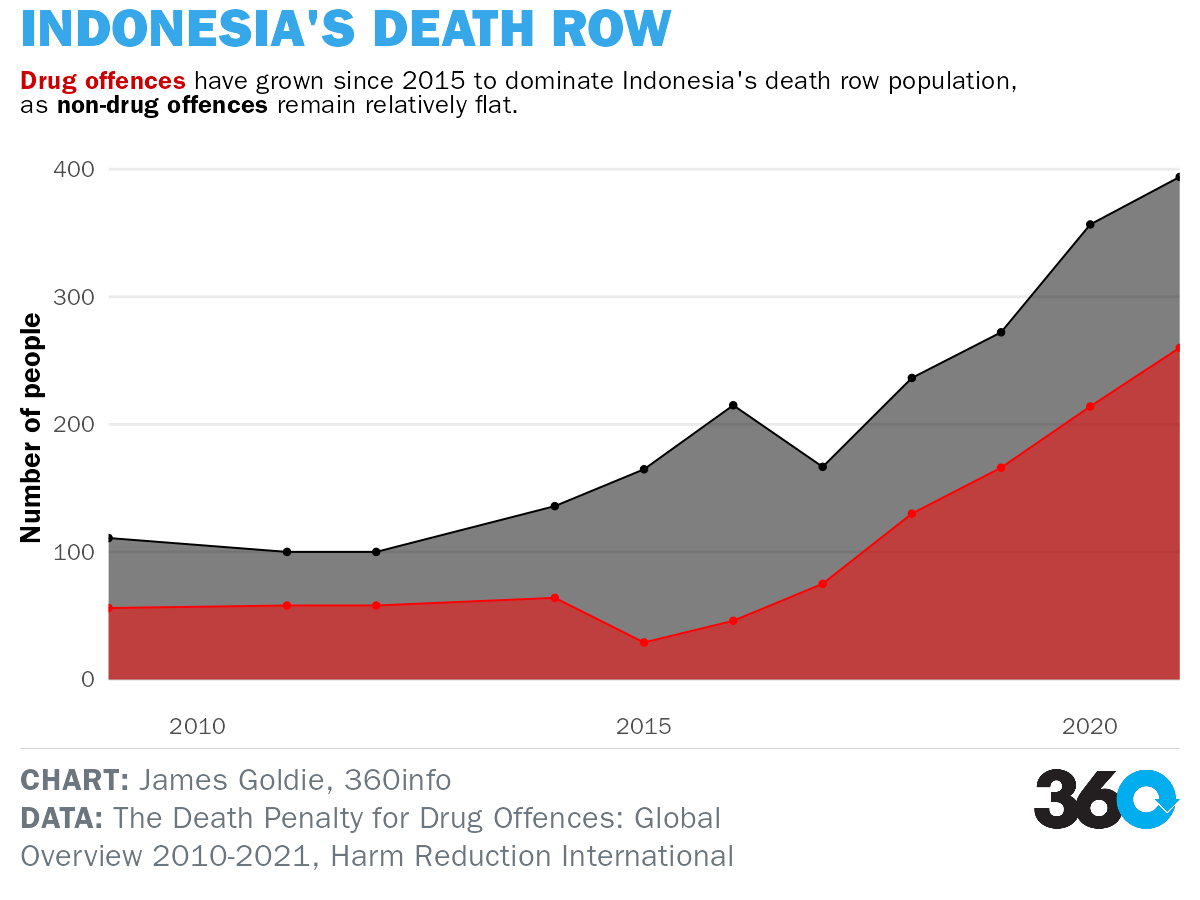

The latest Indonesian Criminal Code is set to replace the penal code inherited from the Dutch colonial government. The Code aims to make a statement about Indonesia’s resurgent spirit, decolonising and democratising the country. However, its approach to capital punishment speaks volumes about the future of the Indonesian criminal justice system — and shows that shedding colonial ideas is often easier said than done.

The government and legislators have agreed to retain the death penalty in the reform, perhaps owing to its long-cited public support in Indonesia. But popularity has not stopped other jurisdictions from scrapping the death penalty — in Mongolia, for instance, President Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj led calls for abolition and went on to win a second term.

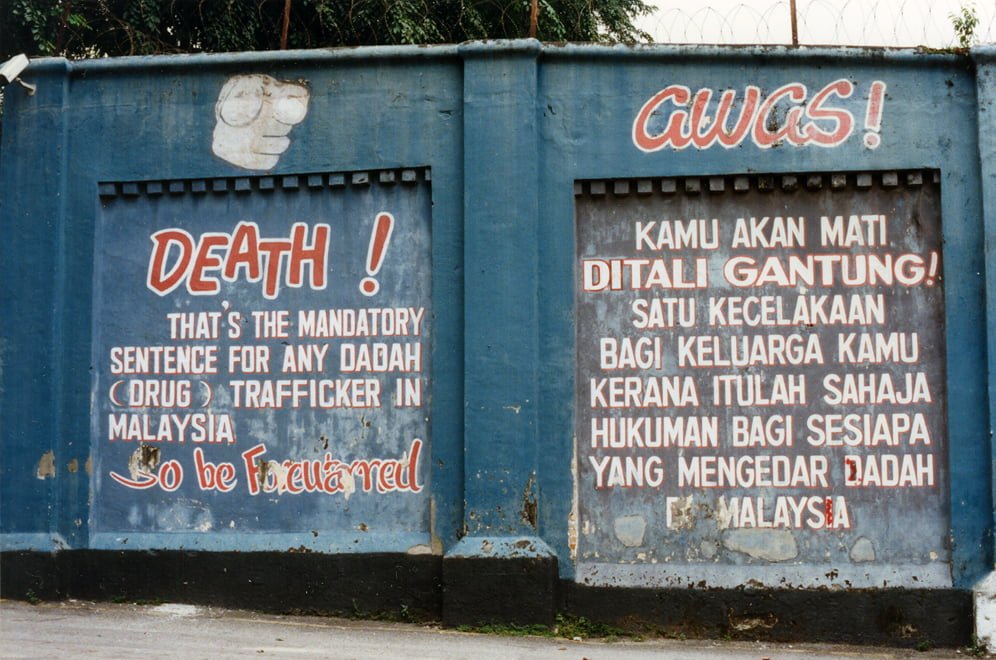

No faction in Indonesia’s parliament opposes the death penalty. Political leaders often promote capital punishment and champion Indonesia’s hardline policy over drug crimes as a way to gain popularity among voters. This situation, coined “popular punitiveness”, describes the notion of politicians using what they believe to be the public’s generally punitive stance for their benefit. Government leaders often cite the retention of the death penalty to flex their credentials as strong leaders that purport to protect citizens.

The Indonesian government and legislators claim the latest provision in the Bill is moderation of the death penalty.

Under the current penal code, the death penalty is one of the main sanctions applied to serious crimes. In the drafted reform, it is a special sanction that can, in some circumstances, be commuted to life imprisonment if certain conditions are met, such as good behaviour while in prison on a ten-year probation. To qualify for the probationary period, a court must consider at the time of issuing the death sentence that the convict shows remorse and hopes of rehabilitation, what role they played in the crime, and whether there are mitigating circumstances.

It is a shift in thinking that implies legislators are thinking more about the death penalty as a last resort sanction designed to prevent and deter crimes.

Despite aiming for a moderated death penalty, the provisions of the death penalty under the latest draft Code have many ambiguities. When determining who qualifies for the probationary period, the court has no guidance on what it means for a convict to “hope to improve himself”. There is also no clarity on the standards of “good conduct” or “remorse”, which sits at the heart of whether the death sentence is commuted. Such openness risks turning the reform into swathes of subjective rulings, particularly in light of alleged corruption in Indonesian penal institutions.

Maintaining the death penalty complicates some of the aspirations of Indonesia’s legal reform. The draft Code emphasises that its punishments aim to rehabilitate, not retaliate. The retention of the death penalty, even in some moderated form, is at odds with such a goal.

Indonesia’s suggested way forward with the death penalty is a middle ground that tries to satisfy a variety of societal interests. It is a typical Indonesian response — the so-called cari aman — which tries to avoid confrontation and conflict by making all happy, even though it does not address the real issue.

But future modification of the death penalty brings its own set of challenges. In the view of Indonesian human rights lawyer Dr Todung Mulya Lubis, abolitionist movements find it difficult to progress in countries with “strong cultural notions of retribution and revenge”, especially countries with an Islamic majority (87 percent of Indonesians identified as Muslims in the last census, in 2010).

Islam is, according to Finnish academic Professor Carsten Anckar, characterised “by the principle of ummah”, which states that the religion is “all-encompassing and that the religious and political spheres are therefore intertwined”.

In a strict sense, Anckar explains, “this means that laws have been made by God and cannot be changed by man”.

Law-making bodies in countries dominated by Muslims must have greater sensitivity to the teachings of the Quran or they risk community discontent. Those who promote the abolition of the death penalty may be at risk of being deemed ‘anti-Islam’.

There is a diversity of views within the Islamic community — progressive scholars such Dr Musdah Muliah have reinterpreted Islamic texts, commenting that retribution or revenge should be weighed against forgiveness, and that the death penalty is not absolute within Islamic law.

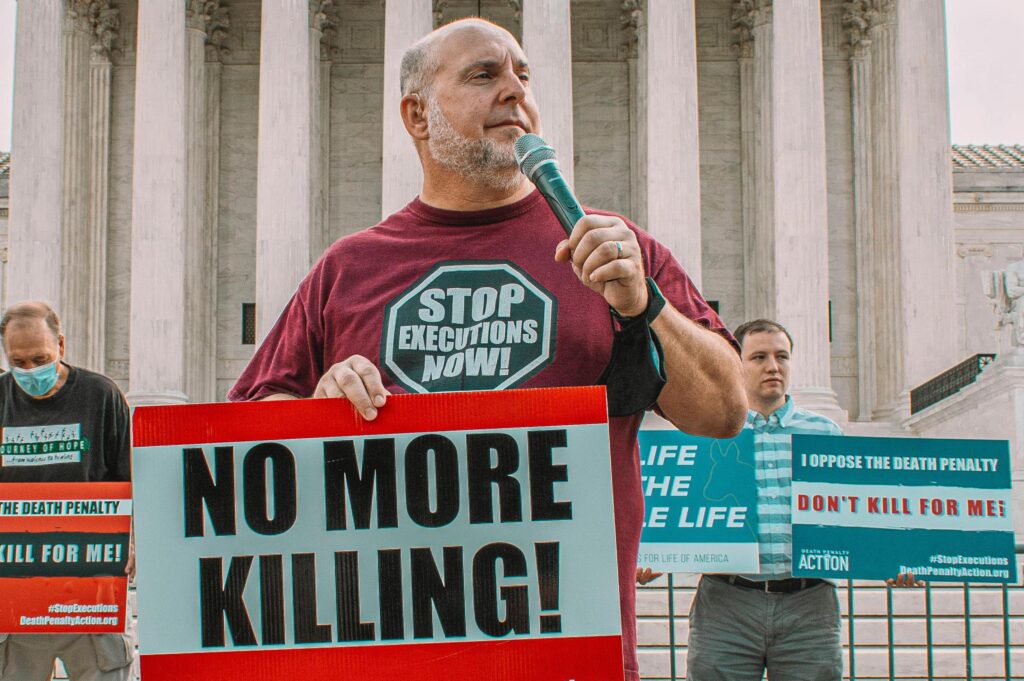

Change is happening, in law and in public sentiment. Legal non-government organisation The Death Penalty Project believes “the government of Indonesia could abolish the death penalty today and the public would accept it”. Even if that is not the case, the attempts at moderation in the draft Code shows some appetite for compromise from Indonesia’s lawmakers.

Amira Paripurna is an assistant professor in the Faculty of Law at Airlangga University, Surabaya Indonesia and a researcher of Human Rights Law Studies (HRLS) UNAIR. Her research is focused on criminal law and criminal justice system, policing terrorism, international human rights law. She declares no conflict of interest and no conflict of interest and did not receive special funds in any form.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.