Indonesia is changing its approach to the death penalty, but half-measures won’t be enough to stop capital punishment outright.

More than a thousand people are on death row in Indonesia. : Purnadi Phan/Flickr by CC 2.0 Purnadi Phan

More than a thousand people are on death row in Indonesia. : Purnadi Phan/Flickr by CC 2.0 Purnadi Phan

Indonesia is changing its approach to the death penalty, but half-measures won’t be enough to stop capital punishment outright.

Indonesia’s new criminal code will ink a new chapter in the country’s judicial history, but it won’t stop the long-standing debate around the death penalty.

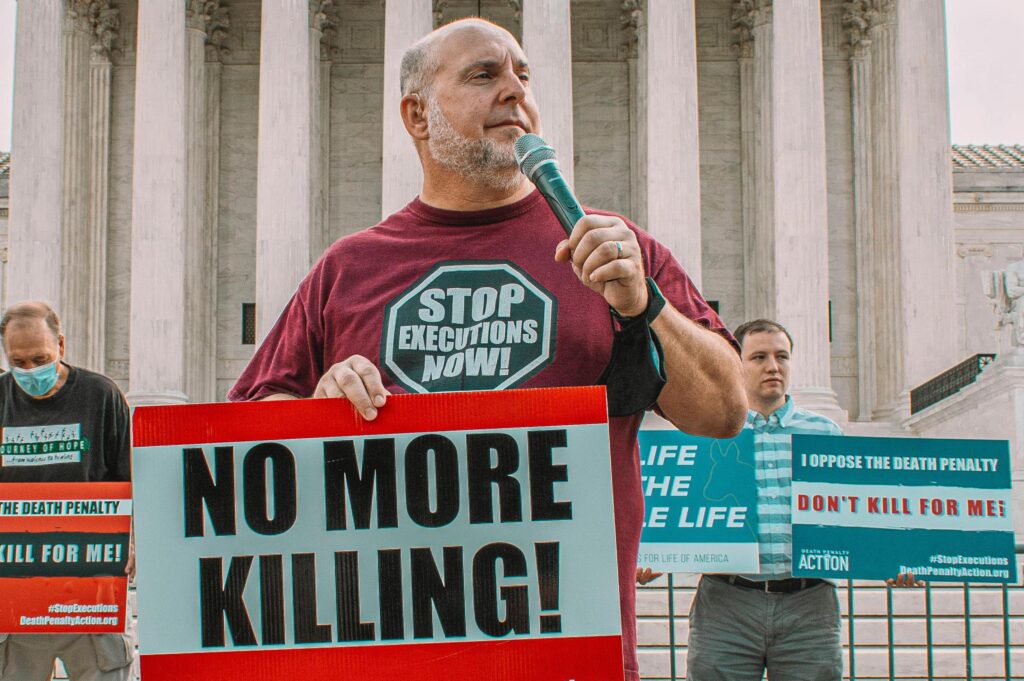

As conservatives and religious groups push for a stronger death penalty, civil societies and academics make the case for its abolition, achieving a moratorium in recent years. The proposed way forward is shaping up as a compromise that may please nobody.

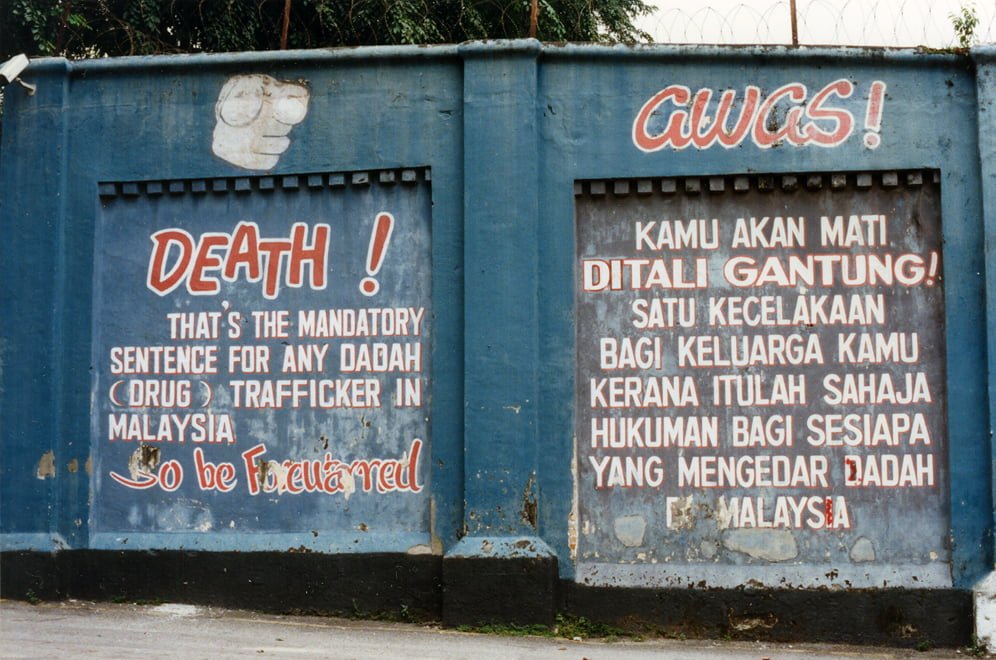

The draft of Indonesia’s new criminal code outlines a reformulated sentencing approach to the death penalty, reserving it as a ‘special punishment’ for ‘serious offences’ such as treason, premeditated murder, major drug-related crimes, terrorism, corruption, and grave violations of human rights.

This approach looks to be aiming for some kind of compromise between death penalty retentionists and abolitionists. Introducing a ten year probational period gives some sentenced to death ten years to demonstrate good behaviour. After the probation elapses, the President has the option to commute their death sentence to life imprisonment.

However, not everyone sentenced to death qualifies for the probationary period. To be eligible, the court considers three factors: whether the defendant shows remorse and signs of being able to be rehabilitated; whether there were mitigating factors around their crime; and what role they played in the crime that was committed (that is, whether they were a leader or an accessory).

This system is closer to international standards for human rights, but will not sate calls to abolish the death penalty from activists. A ten year probationary period will not insulate inmates from the destructive psychological effects of living on death row, which results directly in suicides. And this mechanism isn’t necessary to reform behaviour: where long-term prison inmates have been managed with a focus towards rehabilitation, general positive behavioural changes are detected in less than a decade.

Despite the current moratorium, total abolition of the death penalty in Indonesia appears to be a distant prospect for activists and critics. However, within the confines of mainstream Indonesian politics, there is room to present a version of capital punishment that is more in line with international law.

Indonesia has ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). This United Nations agreement does not support capital punishment but nonetheless outlines indicators and guidelines to determine when such a serious sentence is imposed: it can’t be arbitrary. The death penalty is the most extreme sanction possible, and the law is expected to properly reflect that, for instance, limiting capital punishment to offences of “extreme gravity, involving intentional killing”, as is required by the ICCPR.

To comply with the ICCPR, Indonesia would have to forbid its courts from imposing capital punishment for crimes that do not intentionally and directly result in death. This means crimes such as corruption, political offences, sex crimes, armed robbery, and — most notably — drug offences could not attract the death penalty.

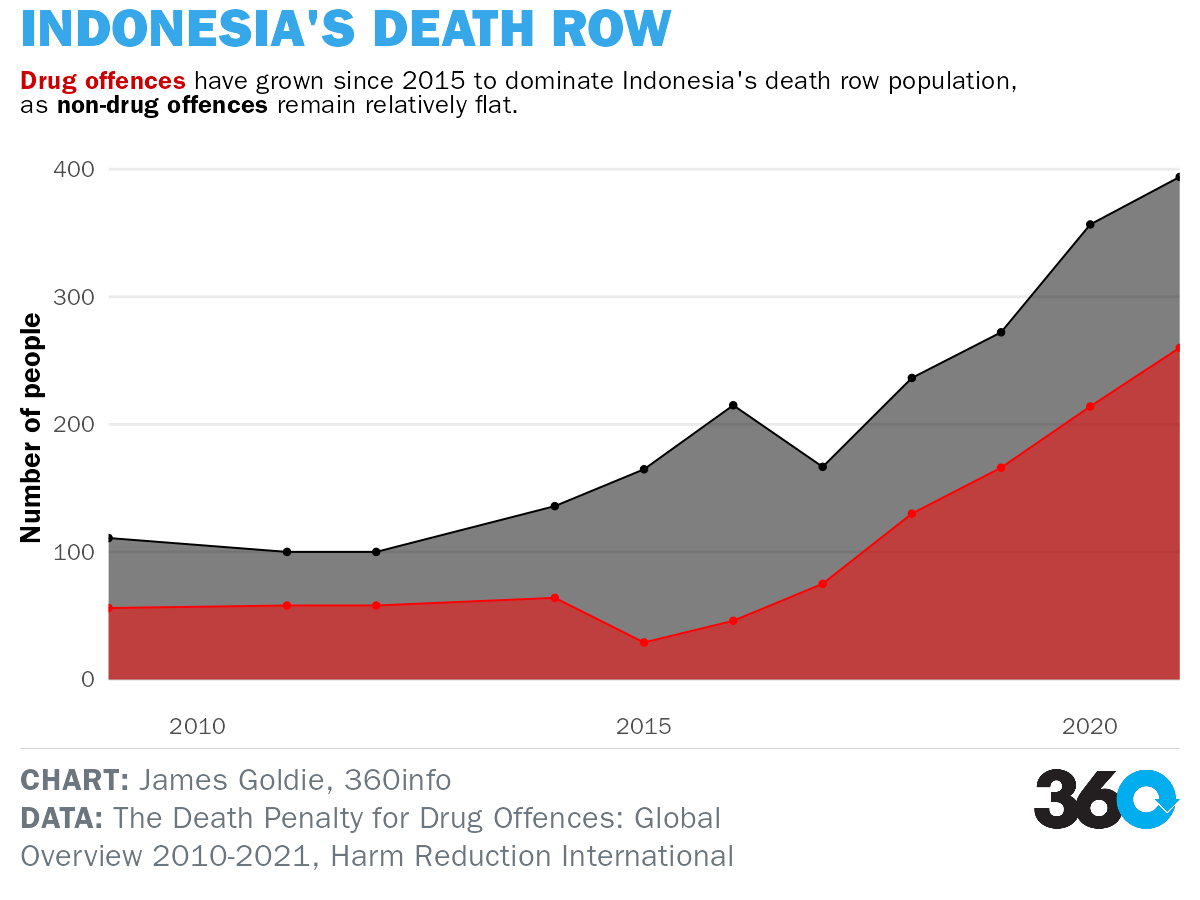

This change would be transformative. In the last three years alone, 516 defendants were either prosecuted or sentenced to death. Indonesia’s death row inmates are consistently increasing, too: from 165 people in 2017 to 404 in 2021. Some 266 inmates are there for drugs-related convictions.

There appears to be some appetite for change, even within the highest ranks of government.

Following a 2017 review of the country’s use of the death penalty from civil society groups, Indonesia accepted two recommendations, placing a moratorium on executions and strengthening monitoring to ensure defendants received their right to a fair trial. Although the pause on executions is a crucial step towards abolition of capital punishment, the uptick in death row sentences over the same period limits some of the momentum.

If the government chose to do so, it could quickly provide far better protections for those facing the courts and those already on death row without overreaching on the judiciary. The government could mandate that the ten year probationary period be automatically given to every offender sentenced to death.

The new criminal code could apply these provisions retrospectively to the hundreds on death row. This would at least provide more certainty over the so-called ‘Indonesian way of the death penalty’, rather than leaving the courts unfettered discretion to play with someone’s life.

Anugerah Rizki Akbari is a non-permanent lecturer at the Department of Criminology, Faculty of Social and Political Science, University of Indonesia. Akbari is actively advocating the amendment of the new Criminal Code in Indonesia. His research interests are crime, criminal law, and criminal justice. A.R. Akbari declares no conflict of interest and did not receive special funding in any form.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.