‘Nudging’ can influence you to do better but it can also backfire

You can ‘nudge’ someone to take up new activities, but unless they truly believe in its value, they won’t keep it up.

There are several ‘nudges’ hotels use to conserve energy and water such as encouraging guests to reuse hotel towels. : rawpixel.com Rawpixel Ltd.

There are several ‘nudges’ hotels use to conserve energy and water such as encouraging guests to reuse hotel towels. : rawpixel.com Rawpixel Ltd.

You can ‘nudge’ someone to take up new activities, but unless they truly believe in its value, they won’t keep it up.

Tired of the constant problem of urine on toilet floors, Aad Kieboom from Amsterdam Airport Schiphol decided in the early 90s to place a small photorealistic house fly near the urinal drain to give people something to aim at. It reduced urinal spillage by an astonishing 80 percent and resulted in an 8 percent reduction in bathroom cleaning costs at the airport.

The fly is one of the most famous examples of a ‘nudge’. And while the majority of research in this area focuses on the positive impact on behavioural change, less research has looked at unintended or ineffective nudges. Some may even backfire, triggering the opposite target behaviour.

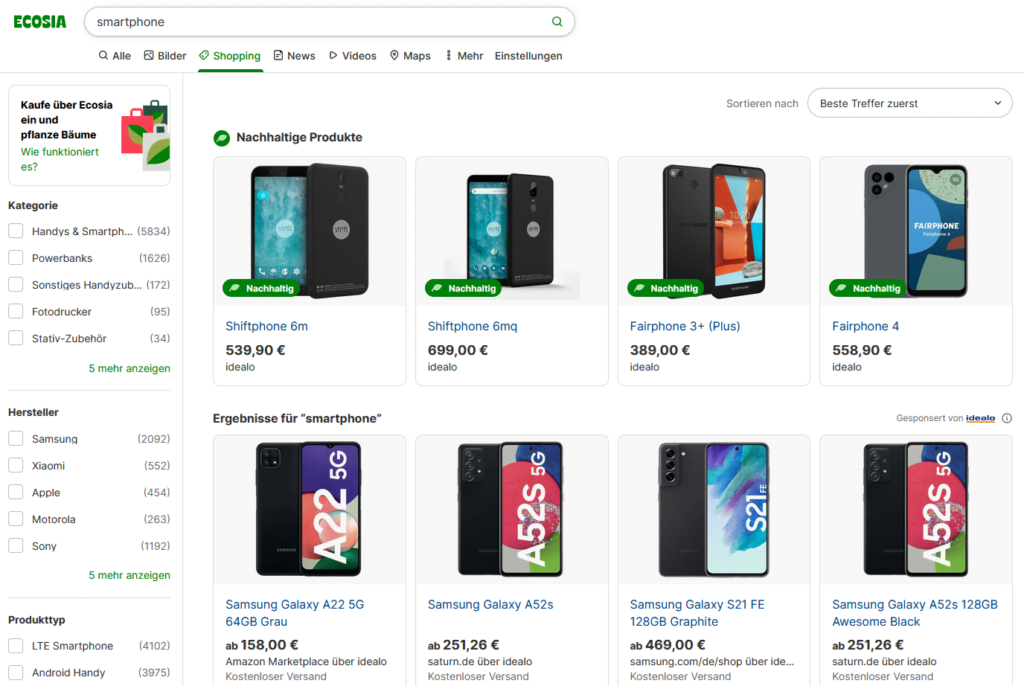

Behavioural theorist Richard Thaler and co-author, Cass Sunstein in a book on the same topic explain that nudges have become an influential marketing and political strategy to deliberately manipulate how choices are presented to decision-makers to steer them toward desired behaviour. Typically, people do not realise they are being nudged.

One nudge method relies on highlighting the decisions of others that may be considered influential. A note in hotel rooms might hint: “Most guests staying at this hotel reuse their towels” making people believe that other guests like them or maybe of higher status are reusing towels. Many people feel compelled to align their behaviour with that of the majority. The decision is theirs, but they’ve been nudged. Sunstein recognises that “If you are told what other people do, you might do it too, because you think it’s probably a good idea to do what they do. And even if you aren’t sure, you might not want to violate social norms, so you’ll go along.”

However, nudging people to make good choices doesn’t always go as planned. For instance, in a study of household energy conservation, researchers provided the residents with information about their neighbours’ average energy use. As expected, those who consumed more energy than the average reduced their usage; however, households with low levels of energy consumption increased their use after learning that their consumption was lower than their neighbours. The researchers guessed that households needed to be told that saving energy is desirable, that the absence of information about the ‘social norm’ could cause the information to backfire. They added a smiley face to the below-average energy users conveying that their low-level energy use was approved, and found that it neutralised the backfire effect.

According to social cognitive theory, people are more likely to commit to a goal when they believe their actions will help. If people anticipate the benefits of their actions, these expectations can influence how committed they are. For instance, someone recycles and makes pro-environmental choices since they value the environmental benefits of recycling and have internalised the value of the activities.

Nudging people is not deception. Nudging often works by raising a particular decision or behaviour’s prominence. If people are already predisposed toward something – like eco-conscious behaviour – a nudge helps tip their mental mechanisms in that direction. Nudging cannot make people do something they do not want to do.

But when the right motivation is lacking, nudging with information about what everyone else is doing can be ineffective and can even be detrimental. When people with low eco-consciousness are nudged into participating in environmentally friendly activities, they experience conflicting behaviours and beliefs. They might soon realise that they were only participating in the activities because of peer information, for instance, and are less likely to believe in the value of the eco-friendly activity. As a result, they become less motivated to change their behaviour. Researchers have found that nudges can even lead to a lower effort when people have not internalised the value of the goal.

Policymakers around the world aim to change people’s behaviour, guiding them toward decisions deemed to serve their or the community’s best interests. In addition, marketers are constantly devising ways to nudge people into buying more to increase profits and sales. Although nudging has been effective in changing behaviour, if the motivation is lacking, it doesn’t stick. Nudging behaviour without first tackling belief and commitment is a recipe for longer-term failure.

Grace Lee Hooi Yean is an associate professor of economics and head of the Department of Economics with Monash University Malaysia. The author declared no conflicts of interest.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.