A maze of eco-labels and certification means consumers are easily confused. A German initiative aims to provide clarity.

Germany’s Green Consumption Assistant flags to online shoppers which products are more sustainable : supplied CC 4.0

Germany’s Green Consumption Assistant flags to online shoppers which products are more sustainable : supplied CC 4.0

A maze of eco-labels and certification means consumers are easily confused. A German initiative aims to provide clarity.

When Berliner, Anna Maierski went online shopping for a new pair of jeans, she was overwhelmed with choice. Not only were there hundreds of jeans from dozens of outlets around the world, some claimed to have eco-friendly credentials. As an environmentally aware consumer, Anna was interested in the eco-labels but wary of ‘greenwashing’ – when companies give themselves fake or puffed-up green credentials to increase sales.

Anna is certainly not the only one to experience such confusion with online shopping. But research shows that when provided with clear and reliable information about sustainability, consumers are willing to, and do, shop greener. A growing initiative from Germany is trying to transform good intentions into real behaviour.

Private consumption is a key driver of climate change and environmental degradation. But although environmental awareness is increasing, sustainable consumption – where consumers purchase the greener option – remains niche.

A lack of detailed and reliable information about the environmental impacts of products was presumed to be the problem. The first sustainability label was Germany’s Blue Angel, back in 1978. In recent years, with a rise in environmental problems and awareness, sustainability labels have flourished.

By promoting transparency and trust in sustainability-related qualities, the labels are supposed to facilitate greener purchasing and encourage companies to improve their environmental performance. In fact, though, sustainability labels have become a confusing “label maze” – too many different labels, no way to compare labels, and lack of credibility. Rather than encouraging consumers to make sustainable choices, the maze of eco-labels may discourage people from reading labels at all.

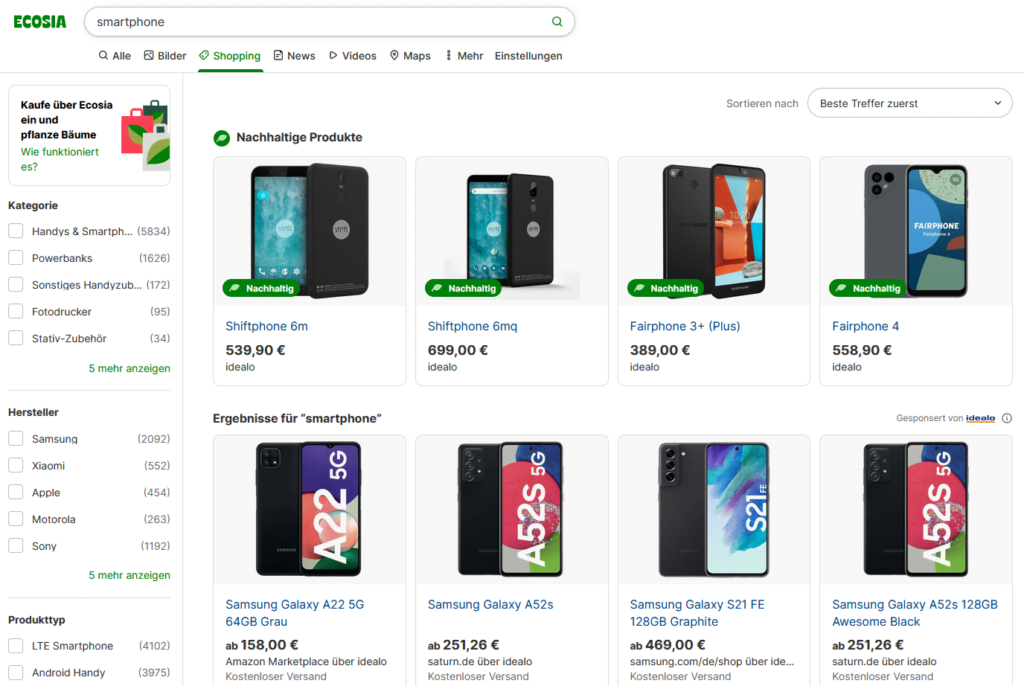

This bamboozling sustainability information and the resulting limited effectiveness of eco-labels were the inspiration for the Green Consumption Assistant, a joint project funded by the German environment and consumer protection ministry. Partner organisations the Technical University of Berlin, the Berlin University of Applied Sciences and Technology and the green search engine Ecosia are developing features that are continuously released, tested and tweaked on the Ecosia website.

Sustainable products are identified in Ecosia’s shopping tab with an easy-to-understand ‘sustainable’ (nachhaltig) banner and a leaf icon on the product images. The aim of the recommendation system is to facilitate sustainable consumer decisions through credible product information direct to people searching online. The products are classified as sustainable based on the German initiative Siegelklarheit (label clarity), which evaluates labels based on a previously developed Sustainability Standards Comparison Tool (SSCT). It is a transparent and reliable ranking of products, unlike many other online-store sustainability tags, filters or browser extensions, which in most cases rely on non-transparent product information or uncertified private labels.

Private labels, which are not certified by a third party, lack independence. There is a risk that some unscrupulous retailers might use private labels for greenwashing, conveying weak sustainability requirements or even disseminating false information to consumers. Even independent labels struggle to weed out underperforming companies.

A recently published report identified a worrying lack of accountability and independence across even well-known initiatives such as Cradle to Cradle certified or the EU Ecolabel. The report found no evidence of enforcement or consequences for companies who committed to targets but failed to meet them. At the EU level, the issue of greenwashing is currently being tackled by the initiative on substantiating green claims. The legal framework proposed aims to ensure companies provide evidence of the environmental footprint of their products using standardised methods.

The Green Consumption Assistant GreenDB database was developed to select and score green products. The database is updated weekly and currently contains more than 300,000 products from the largest online retailers in several European countries. The GreenDB deliberately focuses on products that are in high demand: an analysis of search terms from Ecosia users determined the 26 product categories, currently mainly fashion and electronics.

The GreenDB is publicly available for research purposes and can be used for other AI applications to make sustainability information more transparent and trustworthy. For researchers, the GreenDB has not only promoted sustainable consumption but also provided an overview of sustainability information in online shopping. Only 14 percent of the products in the database are certified with credible sustainability labels. An overwhelming two-thirds of the products in the database have private eco-labels. This shows how difficult it is for consumers to identify sustainable products.

The low uptake of sustainable consumption, the proliferation of confusing, unreliable and niche labels, and the clarity provided by the Green Consumption Assistant all point to the need for a more strongly regulated labelling system. If assigning sustainability tags were exclusive to a familiar and credible third-party-verified label, it would remove some of the obstacles to greener consumption. Previous research has come to similar conclusions. A joint labelling programme by policymakers and retailers could make progress in developing and promoting a truly helpful sustainability label.

Maike Gossen is a researcher at the Department of Social-Ecological Transformation at the Technical University of Berlin. She coordinates the Green Consumption Assistant project and has a PhD on the topic of sufficiency-promoting marketing. Her research focuses on sustainable consumption, sustainability marketing, digitalisation and sufficiency. This research was funded by the German Federal Ministry of the Environment, grant number 67KI2022A.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.