Heatwaves might seem an opportune time to talk about climate change action - but research suggests this could prove ineffectual.

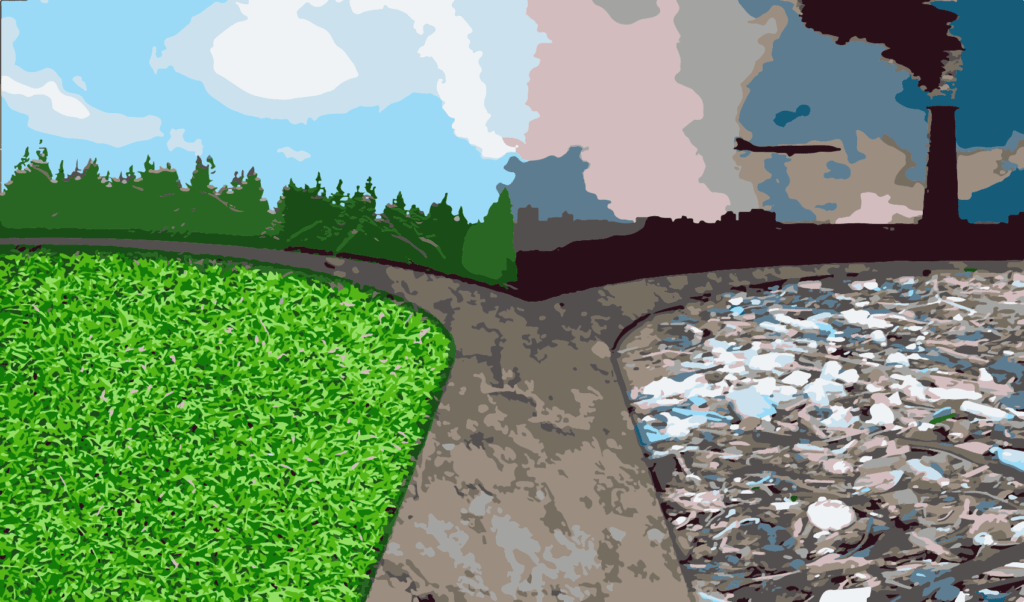

For some, there’s an importanrt difference between weather and climate. : Photo by Mika Baumeister on Unsplash Public domain

For some, there’s an importanrt difference between weather and climate. : Photo by Mika Baumeister on Unsplash Public domain

Heatwaves might seem an opportune time to talk about climate change action – but research suggests this could prove ineffectual.

That climate change is human-induced is not ground breaking news. But it is a trigger for some people in societies where climate change is politicised.

Faced with new information about climate change, they dig into their pre-existing attitudes rather than consider new information with an open mind. This is a problem as people are forced to adapt to the very real consequences of a changing climate.

As large parts of the world are gripped by intense heatwaves, new research suggests talking about adaptation could be more effective at changing some people’s behaviour than making the link between heatwaves and climate change.

For journalists and others who want to provide important information to the public without making the problem worse, the study makes a case for eliminating the phrases ‘global warming’ and ‘climate change;’ and replacing them with ‘weather’ and ‘weather impacts’ instead.

By not using these words, the researchers found people in the study were more accepting of the news stories they were presented with. They felt like the stories’ positions were closer to their own views rather than biased against them, and expressed interest in reading more stories like them, and talking about them with other people. This worked because the study participants felt like the adaptive stories were not trying to manipulate or persuade them as much as the stories that included the trigger words.

Second, the stories included information that people and their communities could use to adapt to extreme weather. For example, a story about heat waves talked about heat stroke and dehydration, cooling centers, and a registry where people can share their information with first responders in advance of an emergency.

This strategy of including things people can do easily represents ‘adapting’ – that is, making smaller, incremental changes rather than monumental tasks required to prevent or reverse climate change. Research on adaptation and mitigation suggests putting the focus on easy-to-implement, incremental actions rather than the cause of the problem would give people more of a sense of control, leading to intentions to do some of the things recommended in the stories. The word ‘adapt’ and its derivatives was also used several times in the stories and headlines.

The study tested these strategies by comparing the same stories – one set written without the trigger phrases and with the adaptive actions, and one set written the opposite way. Except for this, the stories were identical so the researchers have confidence that it was these changes and not something else that caused the results. The study participants included 1,200 US adults, half of whom were skeptical of climate change.

The study is not without its limitations – it only used two topics, heatwaves and rising sea levels, out of a multitude of climate issues. Nor can it conclude that everyone in the US would react the way these participants did. The stories also did not attempt to change people’s attitudes about the issue, but rather aimed to get them to accept the stories and want to read more like them and talk with others about the information. Journalists’ goals are not typically to persuade people to change their behavior, but to give them the information they need to make decisions that are in their own best interests.

The take-away is that there is indeed something journalists can do to educate and engage science skeptics on climate change. Currently, people who need this kind of information the most are shutting down at the first mention of something that conflicts with their beliefs.

It should not violate journalists’ oath to occasionally not repeat the well-worn fact that climate change is man-made. Nor do the authors suggest that journalists never write another story that eliminates this phrase; only that they do so occasionally and when it is not essential to the story.

Language changes are not unheard of in the industry as journalists have recently altered their language in immigration stories, replacing “illegal” and “alien” with “undocumented.”

Making these few small changes in climate news stories has the potential to advance the greater good by respectfully engaging all people in the conversation about what can be done about weather impacts, providing them with much-needed information, and perhaps even reducing polarisation in society.

Renita Coleman, Cinthia Jimenez and Kami Vinton are professor and Ph.D. students, respectively, at the Moody College of Communication, University of Texas at Austin. Esther Thorson is professor at the College of Communication Arts, Michigan State University.

Research funding provided by Michigan State University to Esther Thorson. The researchers declare no conflicts of interest.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.