Indonesia’s young voters: precarious and sidelined by the system

Young Indonesians are told that their votes can make a difference, but the political system offers few ways to address their discontent.

First-time voters know their power, but the political system often works against them. : “Boys and their fixies” by Mindy McAdams is available at https://bit.ly/3PeROL6 CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

First-time voters know their power, but the political system often works against them. : “Boys and their fixies” by Mindy McAdams is available at https://bit.ly/3PeROL6 CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Young Indonesians are told that their votes can make a difference, but the political system offers few ways to address their discontent.

Younger voters have long been a major factor in Indonesian elections. Ahead of the February 2024 general election, analysts and pundits point to the large number of those who will have just turned 17 and are able to vote.

Recent research estimates that the current 17–39 age demographic will make up 60 percent of eligible voters in the 2024 Indonesian general election.

Campaigns by the General Elections Commission, political parties and youth organisations aim to increase political participation throughout the electoral cycle. There are increasing concerns over political apathy and dissatisfaction with the political system.

The campaigns focus on young people as a deciding factor in the elections and encourage them to recognise the power of their vote and their potential to be agents of change.

The myth of youth as an agent of change proclaims the importance of safeguarding the nation’s young democracy. This narrative — with its origins in the mystification of youth’s role in the anti-colonial movement, early post-colonial governance and the pro-democracy movement that toppled authoritarianism — reinforces the ideal of a progressive and nationalist youth identity.

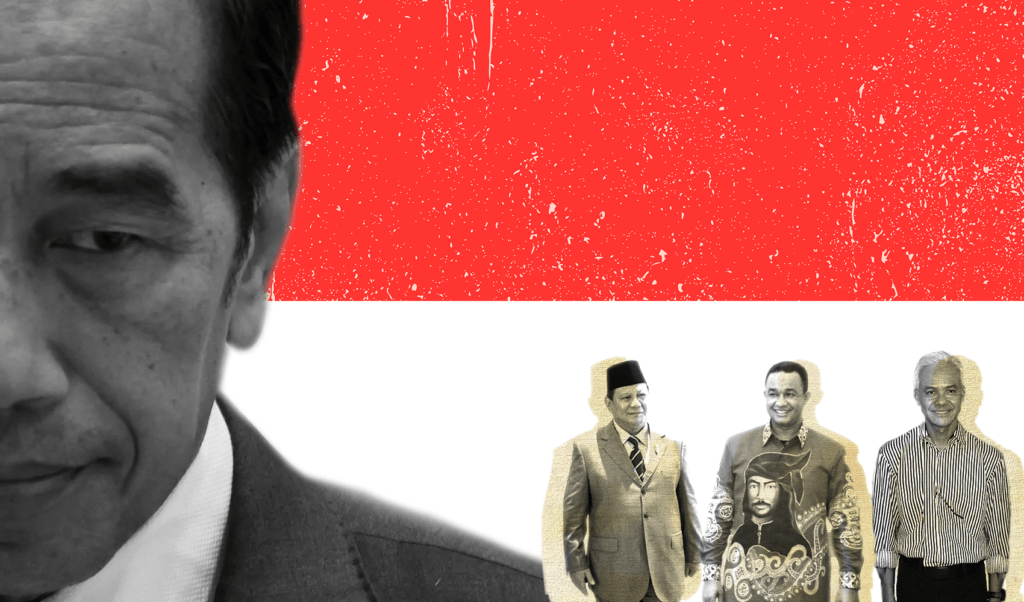

Presidential hopefuls have started to hold dialogues with young voters to make themselves more appealing.

Political parties attempt to sway young voters with targeted slogans: President Joko Widodo proclaims the Indonesian Socialist Party the ‘youth’s political party‘, while Sandiaga Uno of the United Development Party calls his party ‘the home for the youth’.

The National Mandate Party includes popular celebrities and social media influencers in their campaign teams. Parties and politicians also turn to campaigning on social media such as Instagram and TikTok to reach Millennials and Generation Z.

This competition to attract young voters often concentrates on superficial messaging, without offering any real ideas or programs to address the structural underpinnings of youth precarity. And political parties and politicians are major players in a political campaign industry that reproduces populist messages about a divided world.

The generation born in the 1980s is better educated compared with its predecessor, a result of the rapid economic growth under the New Order era of President Suharto (1966–98).

Indonesia also saw rapid growth of tertiary education institutions, especially during the 1990s. These developments suggest that today’s youth have ample opportunities to live up to the promises of education and progress.

But the economy has been unable to generate enough modern-sector jobs to absorb the oversupply of better-educated young workers who aspire to a middle-class standard. First-time job seekers spend months, sometimes years finding a job. Many find themselves in the pervasive urban informal sector after a period of unsuccessful job searching. Most workers in the informal sector do not have employment contracts, employee benefits, social protection or workers’ representation.

Even those who manage to secure jobs in the formal sector — conventionally associated with stable work, protected by employment regulations — can be poorly paid and unable to exercise their rights at work.

Under the New Order, economic growth relied on a cheap and docile labour force, which contributed to factory workers’ exploitation and political repression. The effects of the 1997–98 Asian financial crisis also led to policies that helped accelerate insecurity in the formal sector. The implementation of Manpower Law No. 13/2013, for instance, promoted contract work and outsourcing.

In 2021, the enactment of an omnibus bill on jobs at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic led to more instability for young people entering the labour market.

Contrary to the image of youth as the agents of change, the day-to-day reality is that many are forced into precarious working and living conditions, which are further intensified in crisis situations, such as the pandemic. Underprivileged youth with limited social capital fare even worse.

The political system offers little chance for young people to remedy their discontent. As institutions of democracy have continued to be marginalised, young people’s political agency has been undermined.

Young people also lack effective vehicles for social and political representation, even where democracy is taking root. Such is the historical legacy of the demobilisation and depoliticisation of youth movements under the New Order.

Despite coping with daily insecurity, young people have still helped shape election outcomes. The trajectory of working and living precariously influences their political sensibilities and involvement in elections.

Studies of previous elections have looked at the operation of millennial social media campaigners, popularly known as ‘cyber armies’. These are loosely made up of volunteers from backgrounds ranging from students and office workers to housewives, working without pay.

Several cyber armies became a crucial part of the political campaign industry, working in coordination with professional campaign teams supporting parties and individual politicians.

Their main role was to mobilise voters through promoting divisive narratives — including hoaxes and fake news — and feeding a climate of warfare in the electoral arena.

Accelerated socio-economic uncertainty — often associated with the processes of neoliberal globalisation — has been linked to the global expansion of right-wing populism. Populist narratives gain traction among young people who aspire to upward mobility but face dire employment prospects and struggle to meet basic needs.

Politicians who frame inequality in ethno-religious terms — demonstrated in the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election and the 2019 presidential elections — can provide precarious youth with a way to articulate grievances and make sense of their social position. This makes young people an easy target of populist mobilisation.

Diatyka Widya Permata Yasih is an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology and Deputy Director for Academic Affairs at Asia Research Centre, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Indonesia. Her research activities are centred on increasing precarity in work and in life under neoliberal pressures and its link to social and political developments in contemporary Indonesia and across Southeast Asia.

This article has been updated for a special report on the 2024 Indonesian elections. It originally appeared on September 13, 2023.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.