The presidential contenders are playing up their commitment to fighting an old problem — but with few new details.

Presenting a commitment to fighting corruption has long been seen as a good campaign tactic in Indonesian elections. : Mohammad Rizky ramadhan via Flickr https://bit.ly/4bu7tAk CC BY 2.0

Presenting a commitment to fighting corruption has long been seen as a good campaign tactic in Indonesian elections. : Mohammad Rizky ramadhan via Flickr https://bit.ly/4bu7tAk CC BY 2.0

The presidential contenders are playing up their commitment to fighting an old problem — but with few new details.

As Indonesians prepare to go to the polls on February 14 to elect a new president, along with legislative representatives across national, provincial and local government, the sight of candidates distributing goods like rice, cooking oil and other household items to voters is not out of the ordinary.

Some incumbents might even use their government position to attach themselves to public programs they have nothing to do with – handing out government-procured goods as ‘gifts’, when actually the goods are part of official social assistance programs (bantuan social, or ‘bansos’).

Money politics and vote buying have been normalised in Indonesia over the years, and every election brings with it concerns about corruption. As a result, corruption and how to eradicate it has become a staple topic when voting time rolls around.

‘Anti-corruptionism’ — the rhetorical use of corruption issues to present oneself as the ‘cleanest’ candidate with the strongest commitment to fighting corruption — has traditionally been seen as a compelling campaign tactic, appealing to voters on a popular issue, and this year is no different.

The misuse of state-sponsored assistance is one of several campaign tactics that have raised concerns this election cycle. A national election oversight NGO, Rumah Pemilu, has urged citizens not to be swayed by politicians hijacking bansos for their own campaign purposes and directing social assistance to potential supporters rather than to citizens in need.

Even if candidates claim that the social assistance they distribute is merely a no-strings-attached gift, it’s still illegal. Law No.7/2017 states that candidates are prohibited from offering goods or money to voters in order to influence their decision.

Besides the distribution of goods to attract votes, there is concern about potential ‘dawn attacks’ (serangan fajar), a common tactic in which candidates distribute envelopes of cash to voters the evening before election day.

The Electoral Commission (Badan Pengawas Pemilihan Umum, ‘Bawaslu’) and the Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi, KPK) have both identified this issue as a concern in the 2024 election.

Corruption has never really been out of sight in Indonesian politics, but the past few years have seen some unfortunate developments.

Legislation governing the KPK, once an independent agency with extensive investigative powers, was changed in 2019 to make it an executive agency subject to more oversight and restrictions. As a result, Indonesian Corruption Watch (ICW), a well-respected NGO, referred to 2019 as the country’s “toughest year for the fight against corruption”.

During this past political term, 38 ministers and heads of state agencies have been charged with corruption. Of course, an accusation is not necessarily a reflection of guilt, and there have been suggestions that some allegations are politically motivated.

However, the fact that so many officials have been accused of corruption reflects ongoing challenges in deterring corrupt behaviour. In 2023, corruption cases embroiled the Minister for Agriculture, Syahrul Yasin Limpo, and the Minister for Communications and Information, Johnny G. Plate.

A further issue is that there is no restriction against former corruption offenders competing in the elections. ICW reported that at least 56 candidates running in the 2024 elections had previously been convicted of corruption.

Another organisation, Perludem, has suggested that candidates with a criminal record should have a mark on the ballot papers so voters are aware of their background.

The poor state of Indonesia’s anti-corruption efforts was also highlighted in the 2022 Corruption Perceptions Index, released by Transparency International. Indonesia’s score fell from 38 to 34 (out of 100), representing a drop from 96 to 110 in the world, with its lowest score since 2014. News of the decline was met with commentary that President Jokowi had not fulfilled his promises to strengthen the KPK.

Voters continue to identify corruption eradication as a core political issue, though perhaps not as fervently as in the past.

A Center for Strategic and International Studies study of key issues among young voters ranked fighting corruption as the third most important issue, after social welfare and employment opportunities. Another survey released in December 2023 by Indikator found that only 28.7 percent of respondents felt that current anti-corruption efforts were enough.

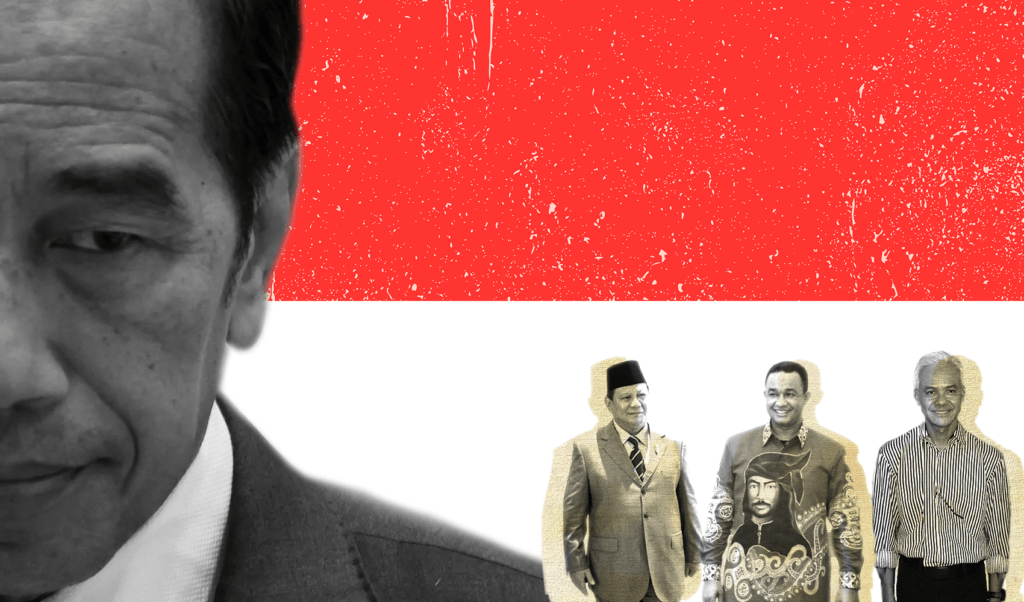

President Joko Widodo, known as Jokowi, cannot contest the election, having reached his two-term limit. With no incumbent in the running, the playing field is wide open for presidential hopefuls to campaign hard on issues they believe matter to the public.

Three presidential pairings — the presidential and vice-presidential candidates campaign as a package deal, like in the US — are competing in this election: Anies Baswedan and Muhaimin Iskandar, Prabowo Subianto and Gibran Rakabumin Raka, and Ganjar Pranowo and Mahfud MD.

Each has their own political history, and the dynamics of each pairing and the political parties they represent have led to extensive academic commentary on the weakening of democracy, the merging of party interests and a lack of institutional accountability.

Prabowo has contested (and lost) every presidential election since 2014, while his running mate, Gibran, is Jokowi’s son. Anies and Ganjar have been Governor of Jakarta and Central Java, respectively, and both tenures have encountered public controversies.

All the candidates have identified corruption as a key policy issue in their ‘vision and mission’ documents, which are submitted to the Electoral Commission several months before election day and include a list of priorities and election promises.

Their platform documents are vague, though they have had the opportunity to expand on their ideas in media interviews and in the first presidential debate. All agree that anti-corruption efforts need to be drastically improved, but there are some fundamental differences among them.

Anies and Muhaimin offer a range of anti-corruption aspirations. This includes improving Indonesia’s Corruption Perceptions Index score from 34 in 2022 to 49 by 2029. Indonesia achieved its highest score of 40 in 2019, so this is an ambitious goal.

The platform includes strengthening the asset recovery laws to ensure officials found guilty of corruption are “made poor”. Also notable is a stated commitment to restoring the independence of the KPK, a veiled critique of what transpired in 2019.

The anti-corruption platform shared by Prabowo and Gibran makes specific mention of the high level of corruption that existed before Jokowi became president, and a pledge to prevent Indonesia from returning there.

Through this framing, Jokowi’s government is positioned as an improvement on previous governments, something to be respected. They make no mention of restoring the independence of the KPK. In contrast, they propose an additional regulatory body that would monitor the activities of the KPK, the courts, the police and the attorney-general.

Of the three presidential pairings, Ganjar and Mahfud have the most visible references to corruption in their platform document. Corruption eradication would be a “foundation” of their leadership, they assert, alongside improving the national budget and digitalising the bureaucracy. They will fight corruption through the use of technology and “strengthen” the KPK, the police and the attorney-general’s office.

A televised debate on December 13 last year brought some added clarity from Ganjar, who made further promises to promote harsher punishments for those convicted of corruption, including sending them to the infamous Nusa Kembangan prison off Java.

In general, however, the debate did not offer any further clarity on the concrete policy actions any candidate would take to combat corruption.

The corruption discussion ended with a three-way agreement that their policies were all heading in the same direction.

Instead of any of the candidates leveraging the issue to gain the upper hand over rivals and present a coherent plan of action, the overarching appeal to voters by all presidential candidates seems to be: “Just trust us, and we’ll give you the details after we win.”

Dr Elisabeth Kramer is a Scientia Senior Lecturer and 2023 ARC DECRA fellow at UNSW Sydney.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: In the story “Indonesia votes” sent at: 12/02/2024 07:57.

This is a corrected repeat.