Jokowi anointed his son and social media reacted as you’d expect

Every election social media is ablaze with polarising content. This year it’s President Joko Widodo who’s stoked the flames.

Indonesian voters changed what to put on social media and this year stirred by Joko Widodo and his son : “People at Desk during Election” by Muhaimin Abdul Aziz is available at https://bit.ly/3SQhMYn CC (Pexels.com)

Indonesian voters changed what to put on social media and this year stirred by Joko Widodo and his son : “People at Desk during Election” by Muhaimin Abdul Aziz is available at https://bit.ly/3SQhMYn CC (Pexels.com)

Every election social media is ablaze with polarising content. This year it’s President Joko Widodo who’s stoked the flames.

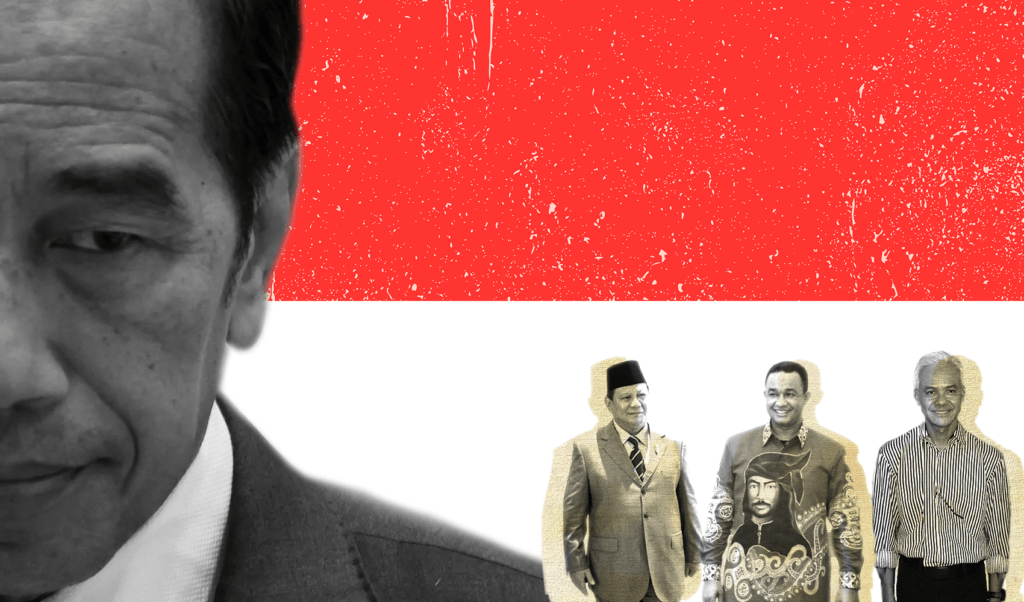

Indonesia’s last two national elections were marked by name-calling wars on social media between supporters of President Joko Widodo and his main rival, Prabowo Subianto.

Jokowi’s supporters were mocked as cebong, a shortening of kecebong, or tadpole. His supporters, meanwhile, ridiculed Prabowo supporters as kampret, a small bat. Both monikers derided the other side’s supposedly inferior IQ.

Things have been different in the lead up to the 2024 election on February 14. With Jokowi unable to run, he and Prabowo have joined forces, meaning most of the polarising comments have focused on Jokowi’s efforts to perpetuate power by inserting his son Gibran as Prabowo’s vice-presidential running mate.

While his supporters believe Jokowi has acted neutrally and fairly in welcoming the election and by continuing to carry out his work agenda, there has been disappointment and anger directed his way by those who see the Gibran nomination as illegal and unconstitutional, with phrases such as “legally impaired” “morally impaired” or “ethically impaired” commonly used.

In our project to monitor hate speech and online polarisation, we sampled and analysed around 42,000 posts between September and December 2023 from X, Facebook, Instagram and articles from a fact-checking collaboration website using keywords selected to capture toxicity and identity.

The anger towards Jokowi can be considered a natural response to his efforts to cling to power, firstly by postponing the general election, then extending the presidential term of office from two terms to three, the merging of Prabowo (Subianto)’s supporter base with his own under the name “Projok”, and, finally, naming Gibran as a vice-presidential candidate to fill the executive seat that Jokowi would vacate.

The polarisation between Jokowi supporters and anti-Jokowi supporters has often created violent clashes of opinion and tension in cyberspace.

Positive messages of government achievements are countered by condemnation and criticism of policies considered controversial.

The most controversial being the decision of the Constitutional Court, which was chaired by Jokowi’s brother-in-law, Anwar Usman, to allow Gibran to stand as Prabowo’s running mate. After that decision, the hashtag #MahkamahKeluarga or “Family Court” as a pun to mock Mahkamah Konstitusi or Constitutional Court, began to appear frequently. Another was #Kamimuak or “we’re fed up” which was expressed as a response to netizens’ anger at Jokowi’s family political manoeuvres.

The dynamics of modern politics, which make social media a battleground for opinions and political beliefs, are complicated by influencers who, voluntarily or under contract, have had their say about Jokowi’s actions.

The involvement of influencers at the inaugural event of the Main House of the Magelang Military Academy on February 2 strengthened the separation of the pro and anti Jokowi camps.

This event incited a social media spat because Jokowi and Prabowo used government events and facilities for the inauguration, and most of the influencers’ posts only mentioned Jokowi’s and Prabowo’s “humility” and “great leadership”.

Misconceptions on polarisation

Based on our observations after the 2019 election, there is a misconception about online polarisation because mainstream media focuses only on social network analysis of X (formerly Twitter) data that showed two big clusters of conversations. But while X conversation on political issues was polarised, it does not necessarily mean society itself was polarised.

The heavy reliance on Twitter social network analysis in the public discussion aligned with the Indonesian government’s goal of controlling the narrative of unified Indonesia and obsession to internalise the state ideology of Pancasila.

As a result, the government’s cultural policy on Pancasila, based on its own definition and interpretation of Pancasila, must be followed by citizens. Under this policy, even a different fashion style, such as wearing a long hijab for women or growing a beard for Muslim men, is potentially labelled as radical.

During each election cycle, there is a consistent rise in hate speech directed at minority groups, often fueled by misinformation and disinformation. This surge in negativity can contribute to the deepening of polarisation, increased discrimination, and the potential persecution of vulnerable communities, including religious and gender minorities.

One way to counter this would be for media to collaborate with universities in devising a monitoring framework to systematically analyse and present data on a dedicated platform.

The findings from this monitoring effort could then serve as a roadmap for the media to generate journalistic content that champions diversity and advocates for the rights of minority groups. This data could help prevent the inadvertent amplification of narratives that perpetuate stigma and discrimination, particularly those propagated by certain political factions.

By using the insights gleaned from monitoring, mass media outlets could identify trends in hate speech usage and refrain from amplifying messages that reinforce negative stereotypes against minority groups.

This monitoring approach could become a valuable resource not only for the media but also for election monitoring bodies, the press council, social media platforms, and minority rights defenders.

In that way, these entities could proactively anticipate and address hate speech, mitigating its impact on social polarisation.

Ika Idris is associate professor at the Public Policy & Management program, Monash University Indonesia. She co-authored “Misguided Democracy in Southeast Asia: Digital Propaganda in Malaysia and Indonesia”.

Derry Wijaya is associate professor at the Data Science Program, Monash University Indonesia. She is the co-director of Monash Data & Democracy Research Hub.

Prasetia Pratama is a researcher at Monash Data & Democracy Research Hub.

Musa Wijanarko is a data scientist at Monash Data & Democracy Research Hub.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.