We use cookies to improve your experience with Monash. For an optimal experience, we recommend you enable all cookies; alternatively, you can customise which cookies you’re happy for us to use. You may withdraw your consent at any time. To learn more, view our Website Terms and Conditions and Data Protection and Privacy Procedure.

Asian democracies struggle under the weight of repression

Published on September 15, 2023Don't look now, but if you're worried about the state of democracies now, just wait until next year.

Across Asia, democracy appears to swing between familiar traps and opportunities as economic realities and expectations evolve. : Michael Joiner, 360info CC BY 4.0

Across Asia, democracy appears to swing between familiar traps and opportunities as economic realities and expectations evolve. : Michael Joiner, 360info CC BY 4.0

Don’t look now, but if you’re worried about the state of democracies now, just wait until next year.

The International Day of Democracy — marked by the United Nations on September 15 — is a motivator for the importance of free and fair societies, but also stands as a glum reminder of its precarious state across the globe.

2024 will be a grand test for the health of global democracy, with the world’s three largest democracies — India, Indonesia and the US — all headed to the polls.

Across Asia, democracy appears to swing between familiar traps and new potentials of the first quarter of the ‘Asian century’, as economic realities shift and expectations evolve.

India and Indonesia have become regional powerhouses, but their paths differ. The contrasts in their economic development speak to a growing maturity across the region.

Next year, Indonesia will elect a new president, following the two terms of Joko Widodo, a softly spoken global statesman who has just hosted the region’s leaders at the ASEAN summit in Jakarta.

For whomever replaces the man they call ‘Jokowi’, youth politics will shape the agenda — 52 percent of Indonesia’s 270 million people are between 18 and 39 years old.

Rachmah Ida writes that with Generation Z and Millennials largely of voting age, “there will be fierce competition for young voters ahead of the 2024 general election”. Much of this approach will come via social media, with TikTok the dominant social media platform among 15 to 24-year-olds.

The use of data to shape political narratives looms large in India. Writing about the rise of digital authoritarianism, Pradip Thomas notes that as the country moves to a cashless, digital society, personal data could be weaponised against dissenting voices.

Twenty-eight opposition parties are working to form a coalition that will run against Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party. Under Modi, India has slid down the global press freedom index rankings as the space for dissent narrows.

In Bangladesh, elections are due by January, but the main opposition party could boycott the vote. Sheikh Hasina’s government has garnered praise from the West, but accusations of human rights abuses and official corruption continue to mount.

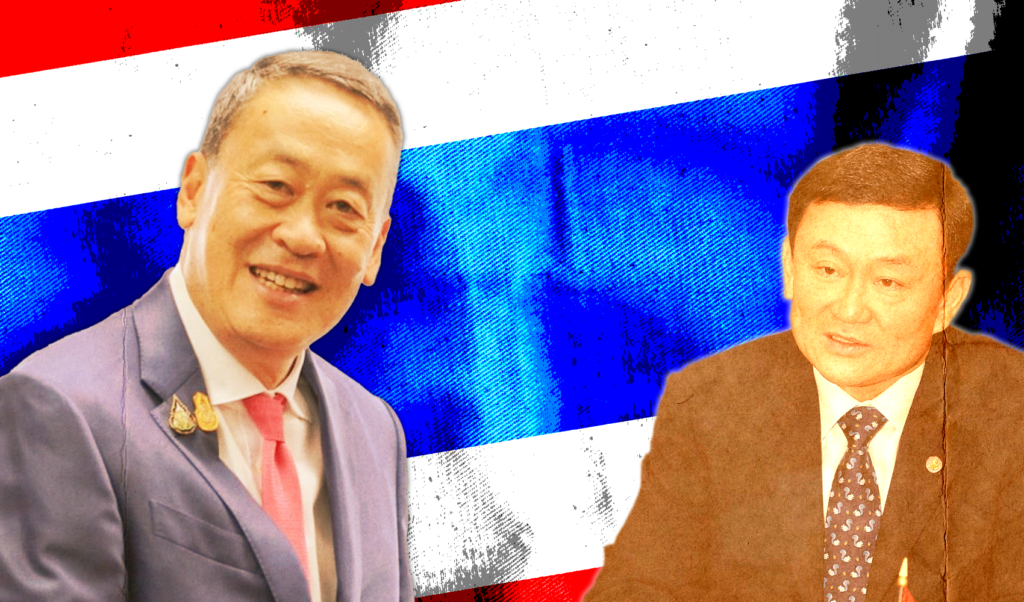

In Thailand, a grand compromise has preserved the country’s veneer of democracy. New Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin was appointed after the party that won the most seats in the May election was effectively banished from power.

Former PM Thaksin Shinawatra’s deal with the royal family and the establishment brought his Pheu Thai party power, while drastically reducing his own prison sentence for historic corruption charges. Michael Connors of Monash University Malaysia writes that the deal “led to this most humiliating compromise for the post-coup generals, whose guiding rationale was the elimination of Thaksin”.

His legacy and the compromised calm of Thailand’s swirling discontent will help to shape 2024 as another crucial year in democracy across the region.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.