Australia is close to eliminating cervical cancer. Could other countries in the Indo-Pacific soon follow suit?

Your chance of developing cervical cancer depends on who you are, where you live and your access to resources. : Unsplash: Rendy Novantino Unsplash Licence

Your chance of developing cervical cancer depends on who you are, where you live and your access to resources. : Unsplash: Rendy Novantino Unsplash Licence

Australia is close to eliminating cervical cancer. Could other countries in the Indo-Pacific soon follow suit?

Australia is on track to be the first country in the world to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health concern.

The latest figures show 6.5 per 100,000 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer in Australia each year, with an estimated 942 new cases of the disease and 222 deaths from it in 2022.

In 2020, the World Health Organization announced a global strategy to accelerate elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem.

The agreed elimination target from that strategy is that fewer than four per 100,000 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer each year.

Modelling by the Daffodil Centre predicts that Australia could reach that target by 2035.

However, in the broader Indo-Pacific region outside Australia and New Zealand, rates of cervical cancer are generally substantially higher. In Timor-Leste, for example, there were 25.6 cases of cervical cancer diagnosed in every 100,000 people in 2020.

There are many factors contributing to higher cervical cancer rates in the broader Indo-Pacific, but addressing the main underlying cause of the disease is essential for reducing these numbers.

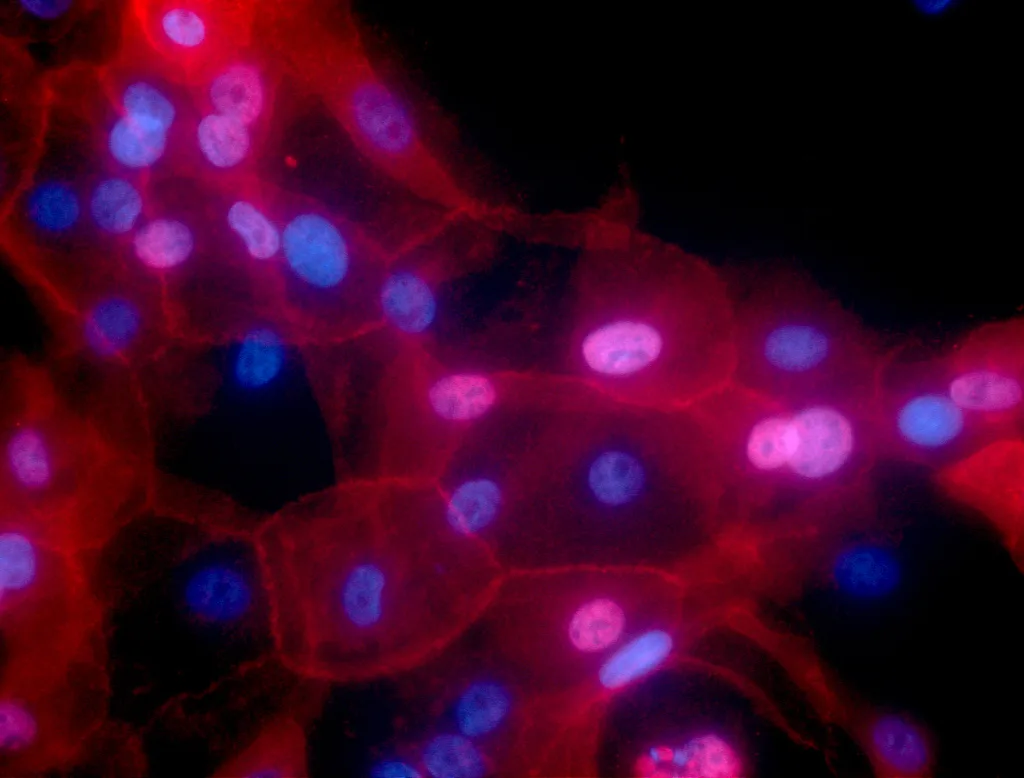

Almost all cervical cancer cases are caused by the human papillomavirus, or HPV, a common virus transmitted through sexual contact. Coordinated screening programmes and vaccination against HPV have proved highly effective in bringing down the rate of cervical cancer.

Much of Australia’s success in reducing the incidence of cervical cancer lies in its already strong organised HPV vaccination and cervical screening programmes.

This was further bolstered in November 2023 by the release of the National Strategy for the Elimination of Cervical Cancer, setting ambitious targets in the areas of HPV vaccination, cervical screening and cervical cancer treatment, and outlining the steps required to achieve these.

Australia’s national HPV vaccination programme is playing a key role in the elimination journey, with around 80 percent of girls and 77 percent of boys turning 15 in 2020 fully vaccinated against HPV.

Vaccinating both boys and girls against HPV means that, over time, there will be wider protection against cervical cancer in communities.

Vaccination remains the best intervention for those under 25, but for people over 25, screening is the most effective measure to prevent the development of cervical cancer.

Even for those 25 and older who have received the HPV vaccine, screening remains important.

Although the vaccine they would have received protects against HPV types that cause 72 percent of cervical cancers, there are several other types of HPV not covered by that vaccine.

This means that, while less likely, they still have the potential to develop cervical cancer, so regular screening is still needed to detect HPV and pre-cancerous abnormalities.

Australia’s National Cervical Screening Program recommends that women and other people with a cervix, aged between 25 to 74 years are screened every five years.

Despite significant progress, cervical cancer remains firmly a disease of inequity.

Inequities exist both within Australia and globally, with low- and middle-income countries facing the highest burden of the disease.

In Australia, your chance of developing cervical cancer depends on who you are, where you live and what resources you are able to access.

In particular, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are more than twice as likely to develop cervical cancer, and almost four times more likely to die from it than non-Indigenous Australians.

To address these inequities, an update to Australia’s screening policy now allows all screen-eligible people to choose between having a sample taken by a healthcare provider, or taking their own sample from the vagina, using a soft swab, like those used for COVID-19 testing.

Both methods use high precision polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing to detect the presence of HPV.

They are equally as accurate for the detection of HPV and subsequently, for the detection of the pre-cancerous abnormalities that the screening programme aims to detect and treat, thereby preventing the development of cancer.

Higher rates of cervical cancer in the broader Indo-Pacific region are closely related to countries’ level on the Human Development Index and their appetite to prioritise the expenditure of precious health dollars on preventative health measures, which directly affects people’s access to HPV vaccination and cervical screening.

However, there are promising signs that countries in the Indo-Pacific will be able to replicate Australia’s success.

While the lack of systematic screening and vaccination programmes is a challenge in some countries, there are several partnerships to support the equitable elimination of cervical cancer across the Indo-Pacific.

One of these is Program ROSE, which has screened over 25,000 women in Malaysia, with delivery of people’s results to their smartphones directly via a digital health platform called canSCREEN, and linkage to follow-up care for treatment, if required.

A recently announced initiative between the Australian government and partnering organisations called the Elimination Partnership in the Indo-Pacific for Cervical Cancer, or EPICC, will enable even more partnerships with countries in the Indo-Pacific region.

These will support the components of an effective elimination strategy, including the implementation of HPV vaccination programs, screening programs and increased access to treatment.

This programme will build on the success of the Eliminating Cervical Cancer in the Western Pacific project, which has led to sustainable cervical cancer interventions in Vanuatu and the Western Highlands province of Papua New Guinea.

Self-collection — for which there is strong evidence of accuracy and acceptability — underpins this critical agenda to address inequity of access to acceptable screening in Australia and around the region in each of these projects.

When supported with linkage to follow-up care, it can be the key to saving the lives of many women and people with a cervix who would otherwise not participate in screening.

Cervical cancer is almost entirely preventable.

Modelling predicts that by achieving the targets set out in the WHO’s global strategy in low- and lower-middle-income countries, over 14 million cervical cancer deaths would be averted by 2070, and over 62 million by 2120.

Professor Marion Saville AM is the Executive Director of The Australian Centre for the Prevention of Cervical Cancer, a visiting professor in the Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology at the University of Malaya and an honorary clinical associate professor in the Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology at The University of Melbourne.

The work referred to in this article has been funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and by the Minderoo Foundation. The Australian Centre for the Prevention of Cervical Cancer (ACPCC) is funded by the Australian and Victorian governments for domestic activities related to cervical cancer control, and has received funding from the Minderoo Foundation for work in Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade has announced funding for the Elimination Partnership in the Indo-Pacific for Cervical Cancer (EPICC). ACPCC is an EPICC consortium organisation and anticipates receiving a part of the announced funding.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.