Australian researchers urge prioritising evidence-based solutions and incorporating Indigenous experiences to tackle rising gender-based violence cases.

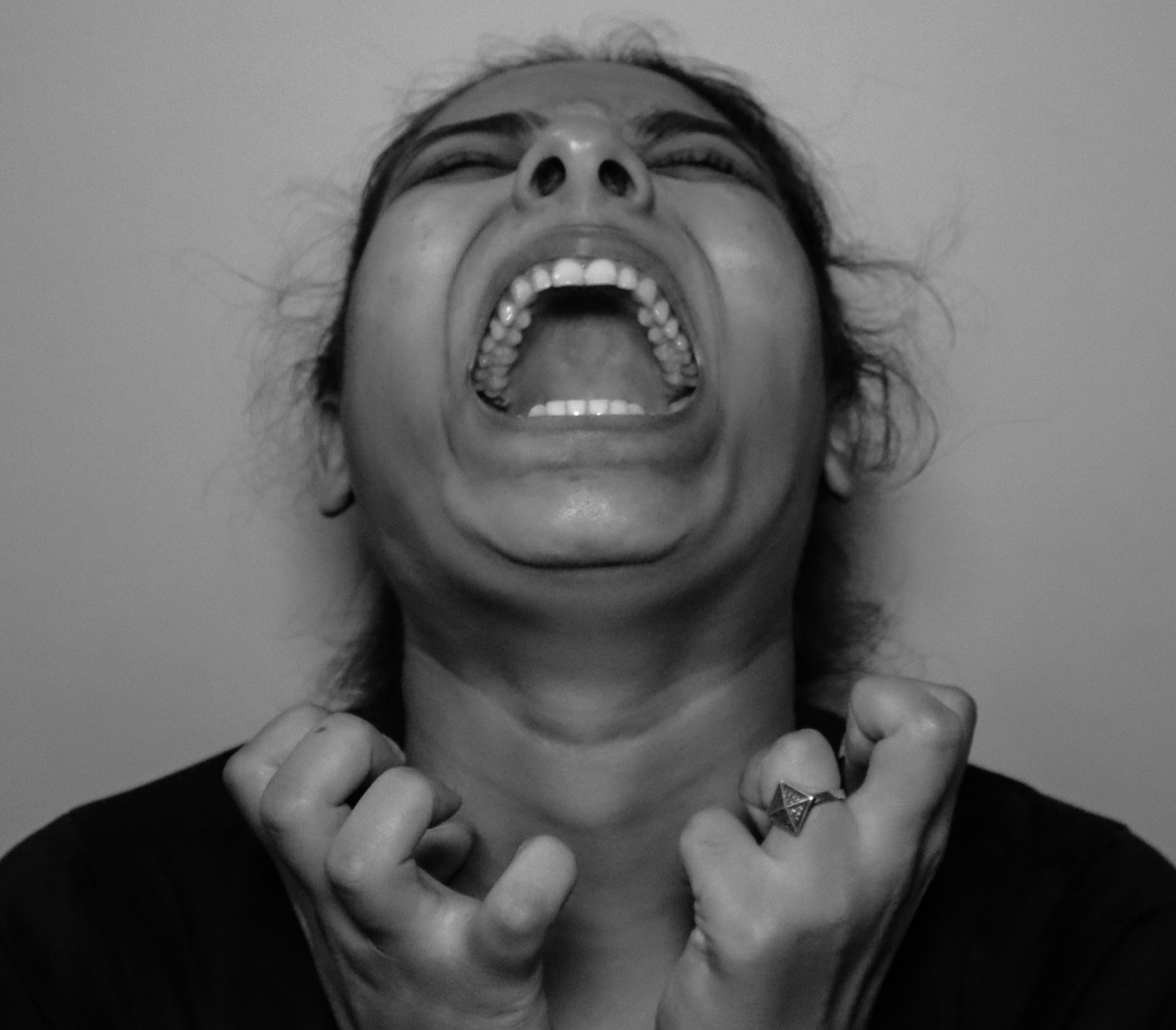

Violence against women remains a pervasive issue. : Kristina Tripkovic, Unsplash Unsplash license

Violence against women remains a pervasive issue. : Kristina Tripkovic, Unsplash Unsplash license

Australian researchers urge prioritising evidence-based solutions and incorporating Indigenous experiences to tackle rising gender-based violence cases.

It is a distressing issue. Gender-based violence continues to thrive in many harmful ways. From systemic discrimination, political oppression, and online misogyny to femicide and domestic abuse.

In 2023, there was a 28 percent increase in the number of women killed by their partners in Australia. However, a shocking disparity emerges from Australia’s latest homicide statistics.

Indigenous women face a homicide rate of 3.07 per 100,000, a staggering figure compared to the 0.45 per 100,000 rate for non-Indigenous women.

This disproportionate violence extends to intimate partner homicides, with 63 percent committed against Indigenous women; and 52 percent for non-Indigenous women.

Despite this alarming reality, these cases often go unnoticed, highlighting a critical need to address bias and ensure justice for all victims of gender-based violence.

While Australia grapples with gender-based violence, many countries still lack robust reporting systems and effective responses.

Within the 23 countries of Oceania, Australia is one of the few where data are collected annually. Gaps in data collection on the experiences of violence limit the efforts to generate knowledge on what works to prevent violence.

In 2010, only 82 countries globally had survey data available on intimate partner violence. That number has since almost doubled in 2024.

Surveys in the Pacific have recorded some of the highest rates of intimate partner violence in the world. In Oceania, the average rate of death due to intimate partner violence is 1.1 per 100,000 women and girls. In Asia, the ‘femicide’ rate is 0.8 per 100,000, although this number is likely much higher due to barriers to reporting violence and registering deaths as the result of gender-based violence.

It was not until 1992 that violence against women was recognised as a human rights violation by United Nations member states.

Most countries have recognised intimate partner violence as a crime for less than three decades. As a result, the evidence base on what works to reduce it is limited, but it is growing.

One of the biggest regional challenges is to recognise gender-based violence as a crime. This is an opportunity for Australia to share its own learning experiences and to learn from others.

Putting the national crisis into the regional context shows that compared to other countries (where there is often very low reporting of violence against women, let alone prevention or responses to this violence), Australia is making progress on a complex problem.

An announcement by Australia’s Federal Government signals a stronger commitment to tackling gender-based violence and the rising tide of online misogyny — itself a risk factor fuelling offline gender-based violence.

This comes after a disturbing surge in online sexual harassment and persistent instances of violence against women on and offline.

Research continues to show that technology-facilitated violence (violence perpetrated with the assistance of digital tools and technologies) and the spread of hateful, misogynistic and harmful content in the digital world precedes real-world violence against women and girls.

Countering online misogyny and its impact on young people and children requires more than a targeted campaign to address extensive extremist content, such as TikTok videos by influencers like Andrew Tate, who promote hitting and choking young women.

It demands an integrated curriculum that educates young people about the harms generated by such content and empowers them to counter it.

Calling intimate partner violence terrorism can help draw attention to it, but it doesn’t change the lived experience of those living this reality, who need holistic care and support to address safety, trauma, and the drivers of violence in their situations.

Being cautious in how we phrase gender-based violence is important, as certain terminology may enhance potential risks to victims, such as increasing a reluctance to report to authorities, especially for marginalised communities, and it may increase the reluctance of those who use violence to seek support to change their behaviour.

Some women are killed by intimate partners. Some by children or other family members. Some women are killed by acquaintances or strangers in deliberate acts. Because each death is different, they require different solutions and approaches for future prevention.

There is no universal intervention or response for reducing gender-based violence in a diverse, multicultural society like Australia or in the richly diverse Indo-Pacific region.

The Australian government’s strategy emphasises targeted, evidence-based approaches and acknowledges the need for diverse solutions.

A key contributor to this strategy is the newly established Australian Research Centre of Excellence for the Elimination of Violence Against Women or CEVAW.

This multidisciplinary centre will focus on building a robust evidence base, incorporating Indigenous research methods and the experiences of survivors to help deliver workable approaches to eliminate violence against women across Australia and the Indo-Pacific region.

Given the rates of Indigenous women who are victims of violence, CEVAW has a dedicated focus on Indigenous-led research — which is severely lacking.

What’s required is a distinct community-centred approach, recognising the local drivers that facilitate violence, and can be used as an opportunity to prevent future violence.

An Indigenous-centred approach with local organisations, local language and leaders to deliver targeted messages will have more impact than any generalised prevention strategies.

Evidence can also be collected from survivors’ experiences and the barriers and challenges they encountered when reporting violence, accessing services, and in recovery.

These experiences will vary significantly. Care must be given to ensure survivors are supported in sharing their stories, and that they can contribute to social, structural, legal and political change, especially those survivors with marginalised voices.

CEVAW also has a dedicated focus on the harms and potentials of technology and online spaces and is producing evidence on how to disrupt online misogyny and harness technology in positive ways to prevent gender-based violence on and offline.

The strategy announced by the National Cabinet and the future work of CEVAW are important steps towards preventing online misogyny and assisting women in escaping gender-based violence.

Prof Jacqui True is a director of the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for the Elimination of Violence Against Women (CEVAW) and a professor of international relations at Monash University.

Dr Asher Flynn is a chief investigator and deputy lead (research ethics & training) at CEVAW and an associate professor of criminology at Monash University.

Prof Kyllie Cripps is a chief investigator at CEVAW and the director of Monash’s Indigenous Studies Centre.

Prof Sara E Davies is deputy director (Indo-Pacific research) at CEVAW and a professor of international relations at Griffith University.

Professor Bronwyn Carlson (Macquarie University) and Professor Heather Douglas (University of Melbourne), deputy directors at CEVAW, and Professor Jane Fischer (Monash University) and Professor Astghik Maviskalayan (Curtin University), chief investigators at CEVAW contributed to this article.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.