More boys and young men are being taught about gender violence, respect and consent, but better programs and online tools will help.

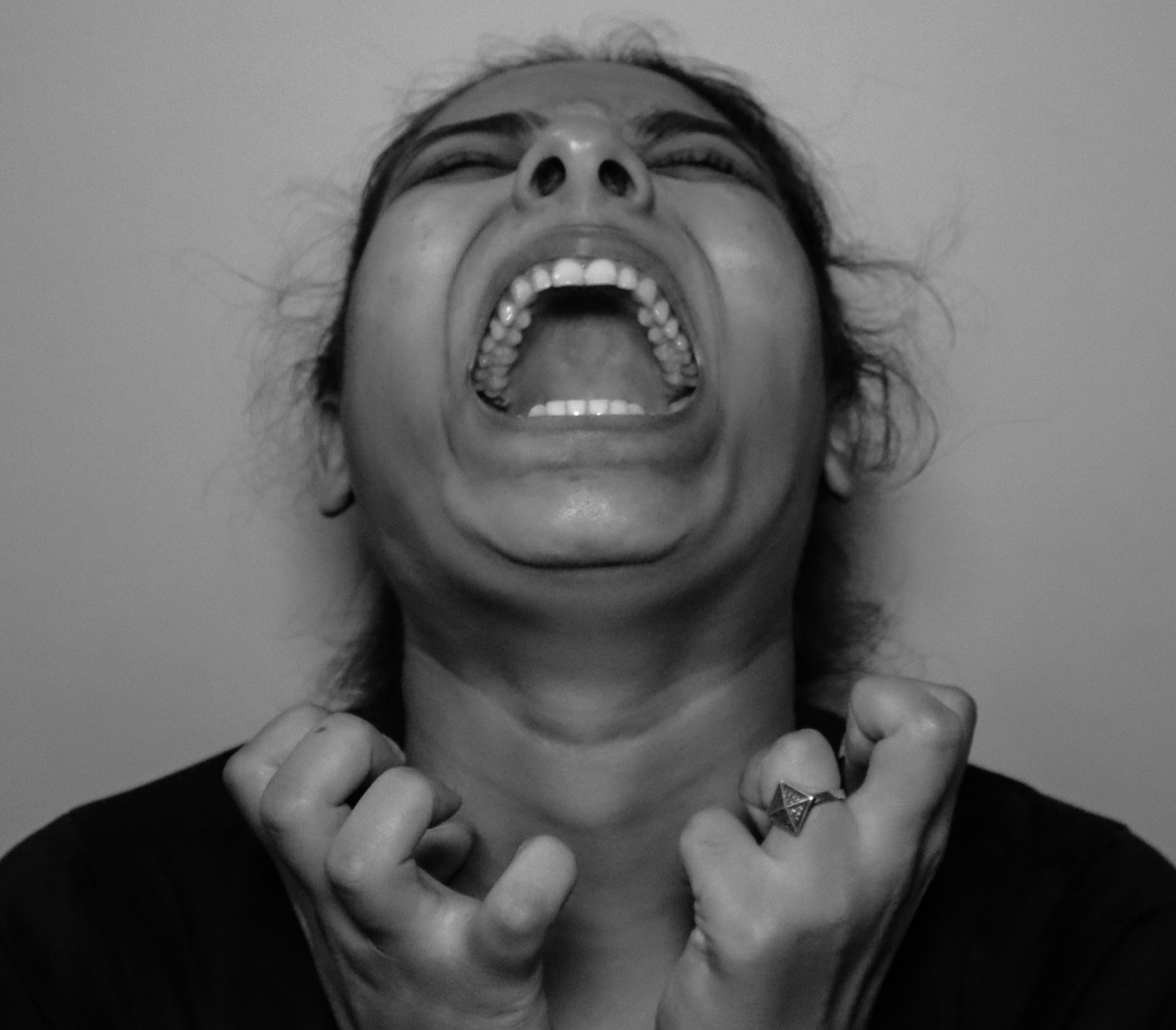

There is increasing attention to involving men in the prevention and reduction of specific forms of violence and abuse. : Temisu via Pixabay Pixabay Licence

There is increasing attention to involving men in the prevention and reduction of specific forms of violence and abuse. : Temisu via Pixabay Pixabay Licence

More boys and young men are being taught about gender violence, respect and consent, but better programs and online tools will help.

In my 20s I joined a march of 400 men through the streets of Melbourne, Australia, under banners emphasising our commitment to ending men’s violence against women.

Thirty-plus years ago, that was one of the first times men joined with women and took collective action to end gender-based violence, but these days such action is not so strange.

As the UN marks 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence, more men are playing a role in ending men’s violence against women and girls.

The numbers of men who take part in efforts such as the White Ribbon Campaign have increased, initiatives focused on engaging men and boys have proliferated in the last decade, and there are organisations and networks engaging men across the world.

More men are speaking up when they hear victim-blaming comments, talking to their sons about how to have healthy relationships, and joining campaigns to end domestic and sexual violence.

There are common pathways to why these men make a commitment to ending violence against women.

Some men hear women’s experiences of suffering violence, whether from a female friend or relative or a public survivor advocate, and realise that no one should have to go through this.

Some men have political and ethical commitments, whether to simple values of fairness or to ideals of justice and equality, and they see that men’s violence is fundamentally at odds with these. Some men are exposed to feminist ideas, whether by mothers or at school or university.

Other men grew up with alternative role models, such as fathers and uncles who modelled respect and non-violence.

Still others feel constrained by traditional, rigid masculinity and support women’s efforts to challenge the gender norms and inequalities that feed violence against women.

Finally, some men are the victims of violence themselves and this fosters a deep antipathy to violence and abuse.

Men’s anti-violence advocacy has existed for at least four decades. My first taste of this work was in the grassroots network Men Against Sexual Assault in the early 1990s: holding rallies and marches, running workshops with boys and young men, and trying to challenge sexist social norms.

However, in the last few years there has been a major surge in interest in engaging men and boys in violence prevention.

Violence prevention programs aimed at men and boys have proliferated.

These include primary prevention programs, intended to prevent initial perpetration and victimisation and aimed at general groups of men or boys, and secondary and tertiary prevention programs, aimed at those already using violence or at risk of doing so.

There is increasing attention to involving men in the prevention and reduction of specific forms of violence and abuse, including sexual violence and workplace sexual harassment.

The work is getting smarter, with growing attention for example to diversities and inequalities among men themselves.

There is widespread community support: a 2020 survey in Australia found that just under 80 percent of people agree that “there are things that all men can do to help prevent violence against women”. Only 4 percent disagreed.

There is growing evidence demonstrating that well-designed interventions can make positive change.

There is also growing policy and funding support.In Australia’s national prevention frameworks and policies, there has been an increased focus on challenging harmful forms of masculinity and engaging men and boys in prevention.

These trends are visible too across the world, where violence prevention policy, programming and advocacy shows increased attention to engaging men and boys.

None of this means that work with men and boys is the only way or the most important way to prevent and reduce gender-based violence. But it does mean that this should be part of our efforts.

The most common violence prevention strategy aimed at males involves educating boys and young men. In schools and elsewhere, programs invite males to think critically about norms of masculinity, teach about healthy and respectful relationships, and encourage non-violence and gender equity.

Well-designed educational programs – multi-session, interactive and participatory, aimed at tackling the gendered drivers of violence and abuse, and taught by skilled educators – can reduce violent attitudes and even actual rates of perpetration.

Other educational efforts are aimed at fathers, men in particular workplaces, male faith and community leaders, and others.

A second strategy involves community development and mobilisation. Although these are less common than education, they are just as vital.

Mobilising men as anti-violence advocates, working in partnership with women and women’s rights groups, is a powerful way to foster both personal and collective change.

Community-level strategies that target modifiable characteristics of the community – structural, economic, political, cultural or environmental – are necessary to reduce the risk of violence perpetration and victimisation.

Communications and social marketing are a third type of strategy. They range from efforts involving print, radio, TV or internet materials to multi-component community campaigns that include on-the-ground events and mobilisation.

Communication campaigns are valuable for shifting the widespread social norms – of male dominance in families, male sexual entitlement, and so on – that feed into some men’s use of violence.

Although engaging men and boys in ending gender-based violence is firmly on the agenda in a growing number of countries, there is much to be done.

We need to scale up the work, as much of it is small and scattered. We need to orient it less towards changing individuals and their relationships and more towards changing the organisations and structures that shape these.

We need to increase the capacity of educators and practitioners to work effectively with men and boys. We need explicit standards for effective practice in work with men and boys, although checklists, funding guidelines, and other principles are starting to emerge.

We must make far more use of online tools and spaces for engaging men and boys, and we must intervene in the sexist online communities through which some boys and men are radicalised into misogyny and violence against women.

Men and boys have a vital role to play, with women and girls, in ending gender-based violence.

Prevention efforts can engage men and boys: to foster non-violence and gender equity, to harness men’s and boys’ positive influence on other boys and men, and to shift the patriarchal masculine norms and cultures that are at the root of gender-based violence.

Professor Michael Flood is a researcher and advocate at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) in Australia.

This article has been republished for a package of stories on gender violence. It was first published on November 24, 2023.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: In the story “Gender violence” sent at: 24/11/2023 11:24.

This is a corrected repeat.