Literacy is not only about rankings. In Indonesia, misconceptions about literacy create a wider gap.

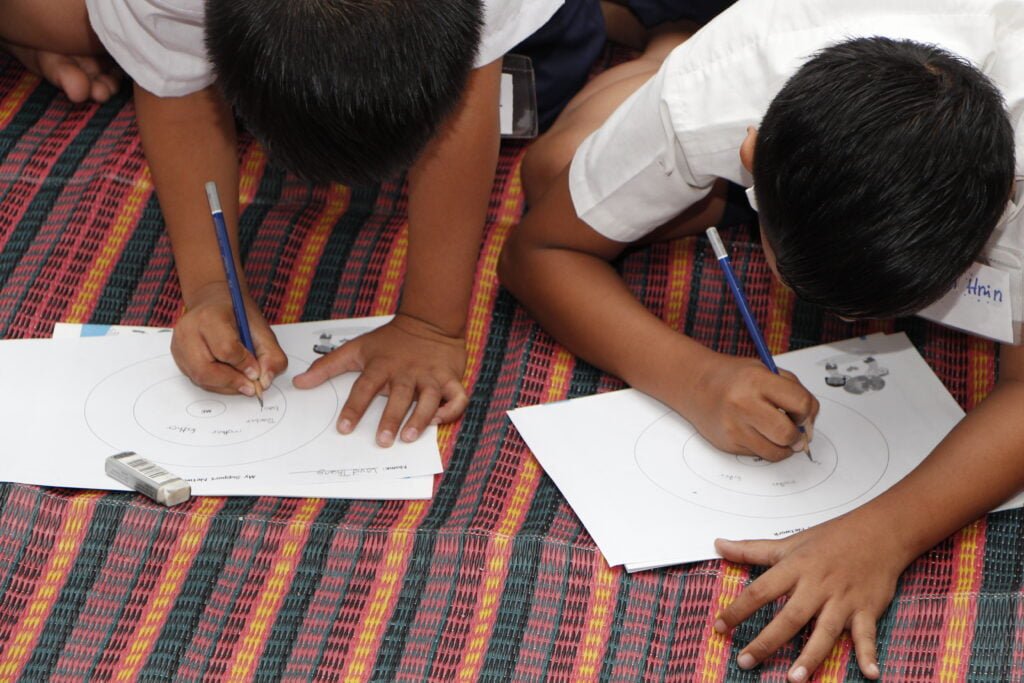

Educational opportunities are not distributed equally in Indonesia. (Asrian Mirza) : Asrian Mirza – ILO Indonesia/Flickr CC by 2.0 Asrian Mirza

Educational opportunities are not distributed equally in Indonesia. (Asrian Mirza) : Asrian Mirza – ILO Indonesia/Flickr CC by 2.0 Asrian Mirza

Literacy is not only about rankings. In Indonesia, misconceptions about literacy create a wider gap.

Indonesia has a celebrated literacy rate of 98.2 percent, claimed by many as a great success of literacy efforts. And yet in the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment, 70 percent of Indonesian students are reported to have low literacy skills.

It turns out there are different ways of understanding literacy – being able to read words is not automatically correlated to high reading ability.

While the world has been celebrating International Literacy Day since 1967, a divide has been deepening in the world of education.

Theoretically speaking, there are two polarised understandings of what counts as literacy. The Great Divide in Literacy – autonomous versus ideological – determines how some people view literacy.

The autonomous model of literacy sees literacy as a mere cognitive process that occurs independently of social contexts. Those in favour of the autonomous model believe the literacy rate is measurable and value free, therefore it can be measured and compared by standardised tests like the national literacy or PISA test. This model is often applied in the theory of teaching, psychology, and development studies. It assumes that introducing literacy as an intervention for the poor and illiterate will enhance their cognitive performance and improve their economic condition, regardless of the socio-economic condition that accounted for their illiteracy.

The ideological model of literacy rejects the autonomous and value-free literacy practices, arguing that literacy is not simply a mechanistic and neutral process. People in favour of the autonomous model believe literacies are locally situated. Reading encompasses sociocultural aspects, including personal and cultural background in constructing meanings from texts. This model is used in anthropology and political science with the aim of social empowerment.

From the autonomous model stem many myths about literacy in Indonesia.

One is that literacy automatically guarantees vertical social mobility. This myth is exacerbated by the fact educational opportunities are not distributed equally in Indonesia. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted unequal access and distribution of learning resources during school closures. Children from poorer households lost more learning than children from wealthier households.

The literacy myth is worsened by the widely held understanding in Indonesia that literacy is simply sounding out the letters and words. The phonemic approach has become an end in itself, rather than seen as the first foundation on the literacy continuum.

At the same time, Indonesia’s legislated focus on 10-15 minutes of silent reading before school starts is ineffective without ensuring students understand the materials, or are guided by teachers on selecting reading materials relevant to student literacy levels and interests.

At worst, gimmicky school literacy programmes see superficial celebration of literacy, students seen posing with books without the associated reading or discussion.

Reading should occur not only in the classroom (intensive reading), but also beyond the classroom, helping to build a reading-for-pleasure culture, something currently missing in Indonesia.

The shortage of libraries is one obstacle to extensive reading in Indonesia. Taman Bacaan Masyarakat (community libraries) can play a role in enabling access to diverse texts, and are known to tailor literacy practices relevant to a particular society’s needs. For example, Sedulur Sikep in Kendeng mountain, Central Java, uses literacy to protest against exploitation and systemic violence of their natural surroundings. And the Women’s March Serang uses literacy practices to introduce and discuss issues of gender inequality, gendered harassment (physical and sexual harassment), and mental health.

Literacy can go beyond the classroom to be more impactful to people. Just as the literacy movement and policymakers can go beyond PISA ranks and standardised literacy tests.

Zulfa Sakhiyya is the Head of Literacy Research Centre at Universitas Negeri Semarang, Indonesia. Her research interests span from discourse analysis, multilingualism and gender. She is the vice coordinator of the Science and Education working group of the Indonesian Young Academy of Science (ALMI) and the co-founder of Indonesian Literacy Educators’ Association. Dr. Sakhiyya declares no conflict of interest and does not receive funding in any forms.

This article has been republished for Indonesia’s National Teacher’s Day. It was first published on September 5, 2022.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.