Literacy finally on the reading list in Indonesia’s curricula

For years, literacy has not been the centre of education in Indonesia. This could change after a long-awaited new curriculum was introduced during the pandemic.

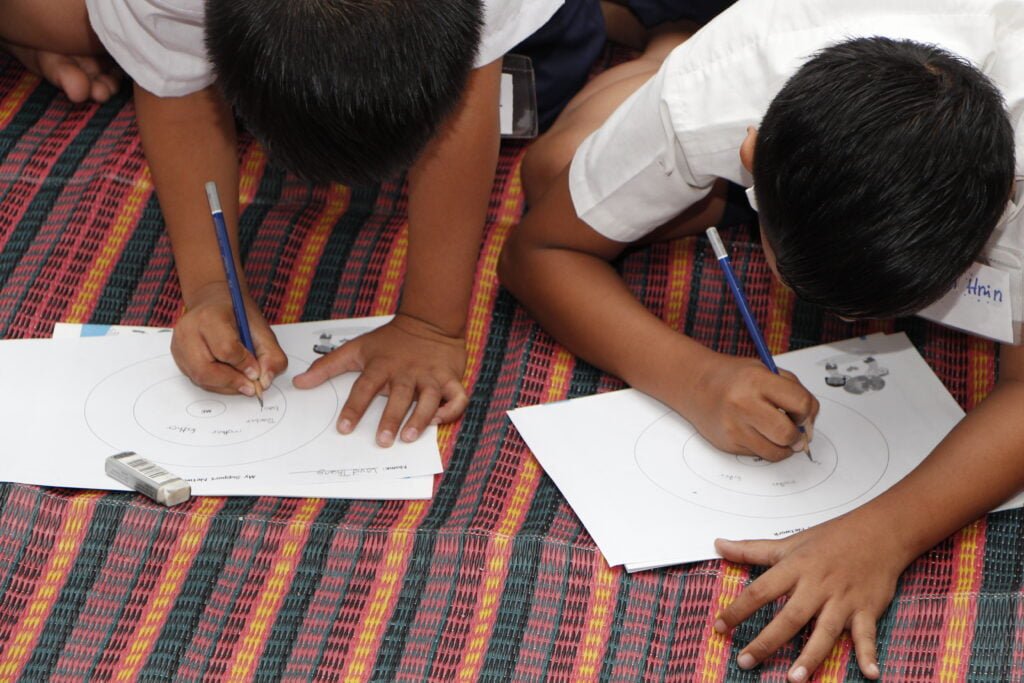

Indonesia’s curriculum is now addressing literacy better (Ariel D. Javellana) : Ariel D. Javellana/Flickr CC by 2.0 2009 ADB. All Rights Reserved.

Indonesia’s curriculum is now addressing literacy better (Ariel D. Javellana) : Ariel D. Javellana/Flickr CC by 2.0 2009 ADB. All Rights Reserved.

For years, literacy has not been the centre of education in Indonesia. This could change after a long-awaited new curriculum was introduced during the pandemic.

When the Indonesian government first set about improving poor literacy levels in 2015 it regulated 15 minutes of reading for pleasure before the start of a school day.

Schools were energised, book displays and literacy festivals flourished, and while awareness of the idea of ‘literasi’ may have risen, the extent to which literacy learning is facilitated in the classroom generally isn’t clear.

Then, in the face of looming problems driven by the removal of face-to-face learning during the pandemic, the government took the opportunity to change the curriculum. Though largely absent from the Kurikulum 2013, the word ‘literasi’ is found substantively in the simplified Kurikulum Merdeka, introduced in 2022.

Literacy in the Kurikulum Merdeka was aimed toward facilitating students’ general capabilities to think and to make sense of their knowledge and foster a love of books. But the Kurikulum Merdeka also embeds a much more coherent theoretical framework for literacy.

In the past there has been a lack of text resources, and teaching instruction, particularly when it comes to the progression of literacy learning at the primary and secondary levels.

The government has also replaced what was a high stakes national exam with Minimum Competency Assessment, moving away from testing contents taught in school, this assessment narrowed the focus on assessing students’ general skills, namely literacy and numeracy. The literacy test measures Indonesian students’ general literacy capabilities of utilising and evaluating the knowledge they learn from many school subjects to formulate and solve problems, that is, critical thinking. This is quite a departure from the old National Exam, which emphasised measuring students’ mastery of school subjects or content areas.

However, improving Indonesia’s literacy education demands more than a piece of national curriculum regulation. More literacy resources (texts/books) and qualified literacy teachers are required to ensure literacy learning in Indonesian classrooms. Making quality book resources available to support literacy learning is a big issue the government must tackle. Non-government services such as Room to Read and The Asia Foundation’s Let’s Read provide free-to-download quality children’s books published by Indonesian nonprofit publishers like the Litara Foundation.

But greater effort could be directed towards improving qualified Indonesian literacy teachers. This is challenging because literacy learning in the Kurikulum Merdeka emphasises nurturing general capabilities and a love of books. For this to happen demands teachers that meet such qualifications.

Literacy teachers should be comfortable engaging students with books for reading skills and discussing difficult topics raised in the book.

For example, amid a classroom book discussion about a girl who rescued her kidnapped brother, one boy questioned an issue of equal payment based on gender. The story triggered his response regarding whether or not a capable girl should receive an equal salary. The boys’ response appeared to come from his home background, where his mother was a full-time housewife, and the father was the dominant figure.

This type of teachable moment allows students to share their points of view with teachers guiding them to think critically regarding gender equality and equity. In many Indonesian classrooms, this opportunity can be easily ignored in class. But in a true literacy classroom, a difficult topic like this should be a norm to discuss.

Tati L. Durriyah (Tati D Wardi) is an associate professor in Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia (UIII) /Indonesian International Islamic University (IIIU). She is the Head of MA in Education. She authored chapters on children’s literature and student teachers’ reading engagement in two books and serves as an external review board in the Journal of Literacy and Language Education (JOLLE) of the University of Georgia. Her expertise in literacy education helps the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology, in devising the conceptualisation and development of literacy.

This article has been republished for Indonesia’s National Teacher’s Day. It was first published on September 5, 2022.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.