Most people who take psychedelics do so on their own or with friends, not in clinical settings. Removing stigma is the first step toward limiting the harm.

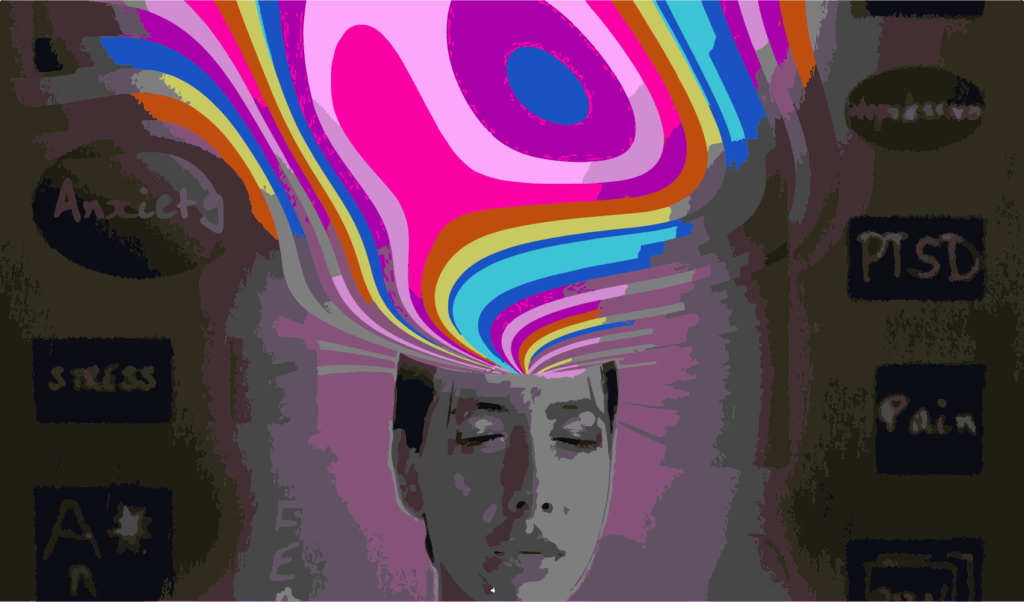

Caring for people under the influence of psychedelics is unique. : Asher Floyd/Wikimedia Commons Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

Caring for people under the influence of psychedelics is unique. : Asher Floyd/Wikimedia Commons Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

Most people who take psychedelics do so on their own or with friends, not in clinical settings. Removing stigma is the first step toward limiting the harm.

International prohibition means most psychedelic drugs are legally available only in research. There are currently around 60 psychedelic clinical trials globally with an estimated fewer than 6,000 people participating in them. But outside of these trials, more than 20,000 people have admitted taking LSD in the last 12 months, according to the 2020 Global Drug Survey. The survey also found the number of people consuming most psychedelics has more than doubled since 2015.

The bulk of recent psychedelic research has explored psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy and drug design chemistry. Research seldom addresses the reality of people who use psychedelics outside of clinical settings. To this day, we know little about how to best provide care to the many thousands of people who use psychedelics worldwide.

Psychedelics come with significant risk of harm. People under the influence of psychedelics have a diminished capability to respond, can perform inappropriate or regrettable behaviour, have challenging or negative experiences, particularly in the re-emergence of psychological trauma, as well as potentially creating new traumatic experiences.

The direct health impacts of these drugs pales in comparison with the harms caused by the shame, stigma and prohibition of using illicit substances. Most harms from psychedelics and other illicit drugs around the world, such as incarceration, addiction and socioeconomic disadvantage, are caused by the prohibited nature of the drug, rather than the drug itself.

Without a legal and controlled drug supply and honest and non-judgemental discussion about drug use, drug misunderstanding, contamination and substitution is common, increasing the risk of overdose. Like harm reduction for all types of drugs, psychedelic care should be grounded in “set and setting” and dosage. Consumers should be in a safe and comfortable place physically (for example, on a couch in a living room) and mentally (such as feeling optimistic and calm).

Many harms can be mitigated by accurately calculating drug dosage. However, few studies can be referred to to provide guidance on this.

Current psychedelic drug dosage and other harm reduction advice draws on anecdotal reports and grey literature — often grounded in grassroots knowledge. Caring for people under the influence of psychedelics is unique due to the specific and distinct effects of these drugs. Psychedelics often produce powerful and long-impacting experiences that consumers describe as mystical or spiritual. Psychedelics have also been described as non-specific amplifiers — intensifying the existing feelings of people who take them. If you’re feeling comfortable and safe, psychedelics might make you feel great, but if you’re stressed, psychedelics could make you feel even more anxious and overwhelmed.

Different psychedelics have different effects, including visual effects like geometric patterns and colour accentuation. Psilocybin typically lasts four to six hours, while LSD may last up to 12. There are different risks with different psychedelic combinations. 5-MeO-DMT, a psychedelic often derived from the dried venom of the Colorado River toad, when combined with ayahuasca, may lead to life-threatening serotonin syndrome, but the combination of DMT and ayahuasca is not likely to. The same drug can produce different effects depending on how it is consumed — vaporised DMT has a different duration of effect than DMT consumed orally.

Care is different for different types of psychedelics and modes of consumption. Smokers of salvia extracts are more likely to require physical intervention from carers, as consumers have been known to behave in unexpected ways, such as jumping through windows or climbing on tables. Consumers of mescaline and ayahuasca are more likely to vomit or defecate. Learning about lived experiences of psychedelics can help set accurate expectations.

Trip sitting is a kind of psychedelic care with the potential to reduce harm. A trip sitter is someone who watches out for a person consuming psychedelic drugs while they are experiencing the effects.

A psychedelic-assisted psychotherapist may encourage a patient under the influence of psychedelics to explore their trauma, while a ‘shaman’ or guide may engage with a psychedelic consumer to direct and navigate an experience. A trip sitter is unlike both these. A trip sitter is likely chosen based on convenience and an existing personal relationship with the consumer. They are normally unpaid, casual roles filled by a trusted friend with experience consuming or caring for psychedelic consumers. Of additional value in a trip sitter is empathy and experience with the health industry, or with other drugs or other altered states of consciousness.

Some psychedelic experiences last for over 12 hours, so trip sitters also need to be patient. A trip sitter aims to be non-intrusive, present in the background of a psychedelic experience, without necessarily interacting with the consumer. Some trip sitters may even do so remotely — via webcam or phone. A non-intrusive trip sitter can be called on to provide support with everyday tasks that may be difficult while under the influence, without intervening unnecessarily. For example, to order food, give water or advice on how to respond to an unanticipated event, or respond to hazards or emergencies that arise like calling an ambulance or administering first aid.

While designing and offering a professional trip sitting service could potentially advance the care provided, such a service would likely be associated with significant financial and legal barriers. Some trip sitting services already offer drop-in trip sitting services at festivals.

A consumer and trip sitter should trust one another and discuss expectations and boundaries before the experience. A strategy for responding to consumer distress, should it occur, should be agreed upon — a hug from a carer is an acceptable response for some but may be considered a boundary violation for others.

Reducing harm for those who consume psychedelics requires a better understanding of psychedelic care. This includes avoiding stigma and supporting people under the influence of psychedelics by anticipating unique drug effects and providing appropriate trip sitting.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, visit Find a helpline for free, confidential support from a real person over phone, text or online chat in your country.

Dr Liam Engel is an ethnobotanist and drug communication scientist working alongside Edith Cowan University’s School of Medical and Health Sciences, Entheogenesis Australis and AOD Media Watch.

He declares no conflict of interest.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.