New political dynamics emerge from Thailand’s surprising compromise

Thailand has astonished observers with a demurely grand political reconciliation to end months of political limbo.

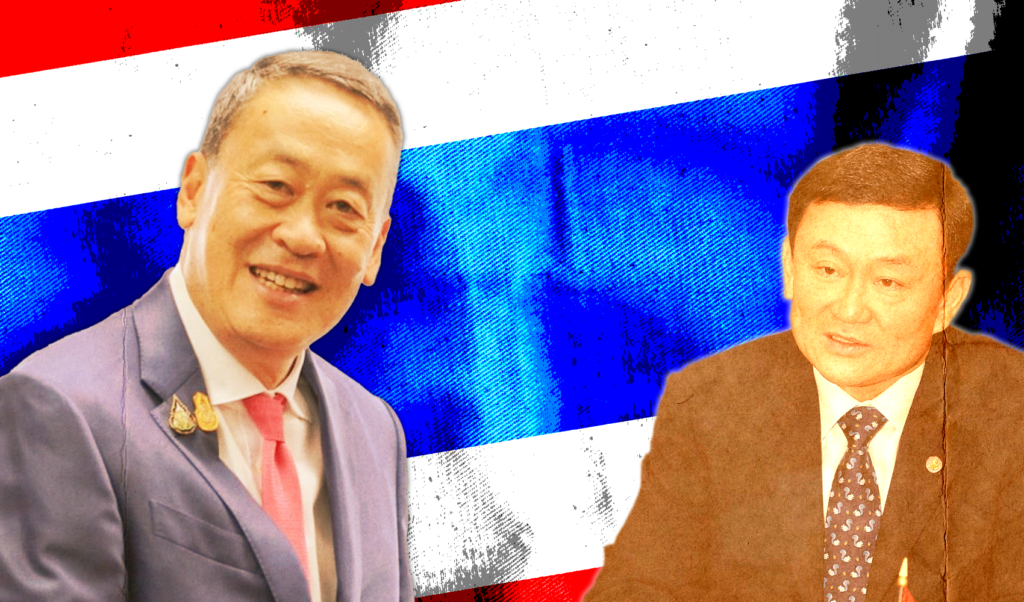

Thailand’s new Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin and former PM Thaksin Shinawatra. : Images via Wikimedia Commons; Illustration: Michael Joiner CC BY 4.0

Thailand’s new Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin and former PM Thaksin Shinawatra. : Images via Wikimedia Commons; Illustration: Michael Joiner CC BY 4.0

Thailand has astonished observers with a demurely grand political reconciliation to end months of political limbo.

In a country already known for complex political bargaining, Thailand’s new coalition government consists of former enemies who have spent much of the past two decades upending the status quo.

Whether the trajectory of this compromise — grandly elite, yet shy in confronting the past — ultimately bends towards the democratic or the autocratic is still up in the air. But the forces for political reform are better arrayed than ever, with parliamentary representation from parties connected to protest and pro-democracy movements going back decades.

In the lead-up to the grand reconciliation, the local Thairat newspaper claimed former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra would offer himself as a hostage for the bargain. He did. Having spent 15 years in self-imposed exile to avoid sentencing for corruption convictions, Thaksin carefully stage-managed his return on August 22. On arrival Thaksin went to prison, receiving VIP treatment. The deal was sealed.

Underscoring the dramatic irony of this elite grand bargain, the Pheu Thai party’s unelected nominee for prime minister, Thaksin ally Srettha Thavisin, was elected by the Thai parliament on the same day.

Thaksin’s Pheu Thai is seen by many as a pro-democratic force. But it appears that the former prime minister directed his party to form a government with military-backed parties associated with the leaders of the 2014 coup that ousted his younger sister Yingluck’s cabinet from office.

That coup and the 2006 coup against Thaksin himself failed to break the electoral strength of pro-Thaksin parties. Instead the coups have now led to this most humiliating compromise for the generals, whose guiding rationale was the elimination of Thaksin.

New political dynamics will now unfold.

When asked about the party’s policy of reforming the military, Prime Minister Srettha replied: “As I have been saying all along, I don’t like the word ‘reform’. My preference is for us to develop (the military) together.” Co-development might be the epithet of the grand reconciliation.

The government is likely to extend the appeasement strategy of ‘co-development’ to other forces, such as the powerful Interior Ministry and societal forces that favour a conservative and highly centralised state. This might bring a new oligarchic business-state compact.

The potential for compromise has been developing for several years. Thaksin was always willing to engage the so-called ‘conservative and royalist establishment’. Ousted from office, he used a popular movement that aimed to restore democracy — the Redshirts — to maintain his bargaining currency in the country. But years of Redshirt protests and election wins in 2007, 2011 and 2019 were not enough to bring his former enemies to the table.

Only when the liberal Move Forward Party won the most seats at the May 2023 election did Thaksin’s opportunity to cash in come into view. The perceived threat of Move Forward’s policies to the status quo, including reforming the military and the royal defamation law, and a revolutionary pledge to democratise provincial government, pushed bureaucrats and soldiers to consider a deal with Pheu Thai.

But first Pheu Thai had to break from Move Forward’s coalition.

Having agreed to form an eight-party coalition government in July led by Move Forward, Pheu Thai played along with attempts to nominate Move Forward party leader Pita Limjaroenrat as prime minister.

But the military-appointed senate, a legacy of the post-coup regime’s 2017 constitution, blocked Limjaroenrat’s appointment, objecting to Move Forward’s agenda of reforming Thailand’s famously strict lèse-majesté law.

Pheu Thai, having also opposed reform of lèse-majesté, then jumped ship and moved to form a new coalition without Move Forward.

On August 31, Thaksin sought a royal pardon. It was granted and published in the Royal Gazette the next day.

The 2014 coup leader and outgoing prime minister General Prayuth Chan-ocha countersigned the pardon, which commutes Thaksin’s eight-year sentence to one year (an earlier parole is likely). The pardon, published in the Royal Gazette rehabilitates the royalist Thaksin: “His Majesty the King granted a reduction of Mr. Thaksin’s prison sentence to one year, so that he could use his knowledge, ability, and experience to contribute to the nation, society, and the people.”

For good measure, Thaksin’s lawyer warned those who might be critical of the royal pardon that criticising the king’s judgement would be to transgress the royal prerogative. The threat is real. Since the youth protests for monarchy reform began in 2020, iLaw has recorded more than 270 lèse-majesté cases.

The prospects for democratic progress are mixed.

Several tiers of protest leadership stretching back to the 1990s and more recent democracy youth movements bring real social change know-how into the mix. Their target will likely be a sluggish Pheu Thai-led government seeking to slow its military and constitutional reform promises to appease its statist partners.

Lèse-majesté reform is unlikely in the mid-term. Instead, reformists will pressure the government to change how the law is policed. They will push the government to deal with legacy prisoners who fought for democracy and freedom of expression or unwittingly got caught up in the defamation dragnet for something as simple as reposting social media.

As reform forces push Thailand along the well-worn road of moving towards democracy, Pheu Thai and Move Forward could emerge as key contenders.

At the next election, there might be a choice between a populist, potentially statist, reforming oligarchy and a liberal democracy. This would be a significant political advance on the prospects of permanent autocracy that the 2014 coup presaged.

But another possibility looms. The reconciliation might congeal into the often military-desired ‘government of national unity’. By default, dissent would be taboo.

As the forces of liberal democracy build on their astonishing accomplishments since 2019, when Move Forward’s predecessor party first won parliamentary seats — only to be dissolved by the courts — a new order of reform with repression can’t be ruled out.

Thaksin will bring much experience to that dim prospect, having done much to dismantle the tentative liberal settlement in the early 2000s. His party now works with the forces that completed the mission in successive cycles of coups, constitution writing, and repression.

Michael Connors is an associate professor in Global Studies at Monash University Malaysia. His recent article on Thaksin and the Redshirts can be found here.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.