Malaysia wants to get rid of single-use plastic by 2030. Bioplastics may help it get there.

As Malaysia grapples with rising food prices, it is important to look at how food is consumed and ways to reduce food waste. : Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0

As Malaysia grapples with rising food prices, it is important to look at how food is consumed and ways to reduce food waste. : Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0

Malaysia wants to get rid of single-use plastic by 2030. Bioplastics may help it get there.

Goodbye, single-use wrap; hello, bioplastics. Malaysia’s ambitious roadmap to phase out single-use plastics by 2030 faces challenges such as food waste and rising food prices. Bioplastics could be the answer – but they will need to be developed, managed and disposed of with care.

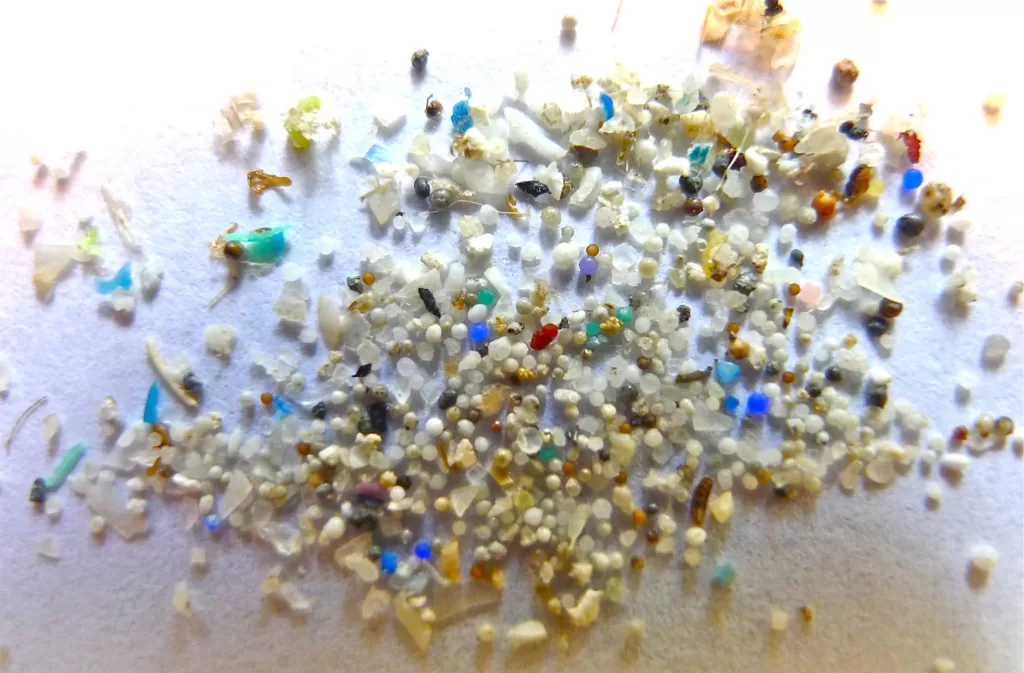

Traditional petroleum-based plastic packaging is strong, versatile and durable but not fully recyclable or biodegradable. It contributes approximately 5.4 percent of global food-system greenhouse gas emissions – far more than any other part of the supply chain, including transportation. Without effective packaging, though, food waste may increase. And it’s already a big problem: Malaysia wastes 17,000 tonnes of food daily. Every kilogram of food thrown into landfill produces the equivalent of 2.5 kilograms of greenhouse gas.

It leaves policymakers to choose between the two evils of plastic-waste emissions and food-waste emissions.

Malaysia’s roadmap encourages local industries to embrace biodegradable and compostable plastic alternatives. These products protect food as effectively as petroleum-based plastics, but they are designed to degrade in a controlled environment of high temperature and sufficient oxygen and require industrial composting.

Plastic alternatives not fully broken down and composted will simply end up in landfill, so their biodegradability needs to be verified to ensure they do not pose an environmental hazard. Alternatively, a nationwide integrated waste-management system is needed to process plastic-alternative waste. The current sustainable packaging alternatives are biodegradable polymers derived from natural sources (carbohydrates, proteins and fats) or synthesised from renewable materials (microbial production, plant biomass).

These biopolymers are safer alternatives for human health and the environment. Compared to traditional petroleum-based plastics, though, biopolymers cost up to three times as much to make, which has limited the growth of the biopolymers market.

A research group at Monash University Malaysia is working to produce affordable biopolymer film using renewable raw materials. Biopolymer-based packaging materials decompose quickly and do not produce toxic compounds. Cost and scale have prevented widespread use of these materials so far, but biopolymers derived from natural sources could ultimately be a cheaper plastic alternative.

Malaysia has been slow to adopt biopolymer-based packaging. Evidence-based studies and new biopolymer-based products are needed before plastic alternatives will appear more often in the food industry.

Support from manufacturers, suppliers and business operators is essential if Malaysia is to achieve the goal of its roadmap by 2030. Industries could work with government, research institutes and universities to drive the growth of commercial products using biopolymers.

Thoo Yin Yin (ORCID 0000-0002-2581-1112) has teaching and research responsibilities in food science and technology. She is a researcher at Monash University Malaysia with expertise in biopolymer-based packaging and alternative methods of preserving and processing food.

The author has declared no conflict of interest in relation to this article.

This article has been republished for World Environment Day 2023. It was originally published on June 9, 2022.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.