More Indonesians are eating fish as part of their regular diet but microplastics do make it risky. There are ways to mitigate that risk.

Human eat microplastic through fish : “Plastic linked to disease in coral” by ARC CoE Coral Reef Studies Australia is availabe in https://bit.ly/3HySaIF ARC CoE for Coral Reef Studies/ Kathryn Berry

Human eat microplastic through fish : “Plastic linked to disease in coral” by ARC CoE Coral Reef Studies Australia is availabe in https://bit.ly/3HySaIF ARC CoE for Coral Reef Studies/ Kathryn Berry

More Indonesians are eating fish as part of their regular diet but microplastics do make it risky. There are ways to mitigate that risk.

Susi Pudjiastuti, Minister of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries of Indonesia (2014-2019) once made a popular joke about Indonesians who didn’t eat fish: “I will go after you who don’t eat fish, you will be sunk like those vessels.” The vessels she referred to were foreign fishing trawlers. The word “sink” became a popular meme on social media and underscored how important fish is to Indonesians.

Fish is a crucial source of protein for Indonesians. Indonesia is the second largest fisheries producer after China and the industry plays a huge role in the country’s economy. The sector is only expected to grow, especially in aquaculture, with traditional catches decreasing due to overfishing. Coupled with a global consumption trend that is starting to switch from red meat to fish, fishery products are becoming easier to obtain and more affordable.

But there is a risk. Eating fish while they are also eating plastic can be dangerous.

Because water quality continues to be degraded, the quality and quantity of fish caught and cultivated also decreases, mainly due to inorganic waste that is difficult to decompose such as microplastics. It is estimated that by 2050 there will be more plastic waste than fish in the sea.

Indonesia is the second largest producer of plastic waste in the world after China. Plastic use in Indonesia continues to increase, spurred by the development of the packaged food industry. Although the public is not generally concerned about the adverse effects of plastic waste on the environment and health, plastic pollution is becoming a big problem, with cases of illegal entry of plastic waste from some developed countries worsening the problem.

The handling of plastic waste in Indonesia has not been well integrated, especially in densely populated rural areas where there are no garbage disposal facilities. This means plastic waste is either burned or thrown into waterways.

Burning plastic produces toxic air pollution and has been banned except under exceptional circumstances. Pollution from burnt plastics also ends up in the soil and water due to the leaching of the remaining material. The easier option is for people to throw unwanted plastics into waterways. The sight of people throwing plastic waste over bridges has become a common in Indonesia.

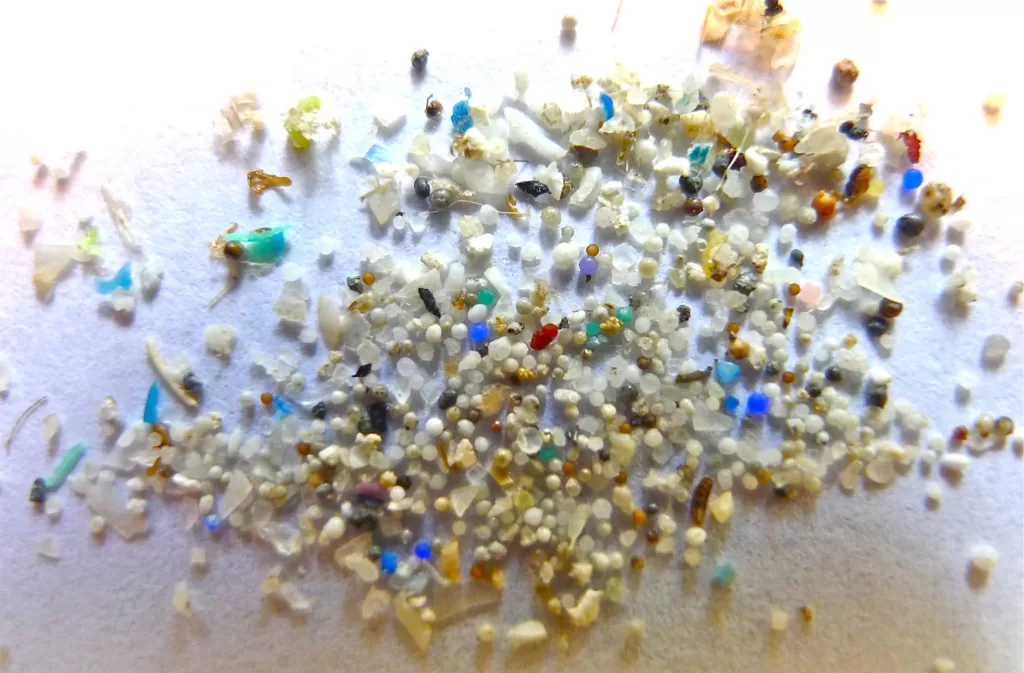

One of the risks of all this plastic floating around waterways is that it can contribute to flooding. It also breaks down into microform (less than 5 mm). It is these microplastics that put aquatic life — and the humans who rely on it — at risk.

Fish are opportunistic feeders and tend to eat objects in the water that resemble their food. In general, fish cannot distinguish between natural food and microplastics because they can be the same shape and colour. Microplastics then settle in the digestive tract of fish. This can lead to unhealthier and reduced fish populations due to malnutrition. For humans, the microplastics in fish can still be avoided by cleaning the fish’s digestive tract before consuming them. This is considered the easiest way to prevent microplastics from being ingested.

There is still the problem of smaller fish, such as anchovies, which are consumed whole. Microplastics are destined to enter humans and end up in our digestive tract. An accumulation of these foreign materials can have dire consequences for human health, such as digestive disorders and even poisoning.

It’s not only fish which carry risks. Drinking water can contain nanoplastics (less than 100 nm) which are barely visible to the naked eye. Most Indonesians rely on drinking water from the nation’s rivers which have been polluted by plastic waste for years. Microplastics are found in almost all rivers in Indonesia and have ended up in processed foods, packaged beverages, and even breast milk.

One environmental NGO found microplastics contamination in 68 rivers from 24 provinces in Indonesia. There are between 6.36 to 4.17 particles per litre. From thousands of respondents to one survey, 90 percent agreed that Indonesian rivers are polluted but they are ready to voluntarily help clean it up.

The solution to the microplastic problem lies with three sections of society.

There needs to be community participation in dividing waste according to criteria such as organic and inorganic waste, especially plastic. This division will make it easier to recycle waste. Organic waste can be processed into compost, while plastic waste is converted into plastic pellets which are ready for reuse.

The industry has so far paid little attention to the plastic waste generated from their products, because they think that products that have been released and consumed by the public are the responsibility of the community. The plastics industry needs to be encouraged to provide waste processing facilities and systems according to the product criteria produced.

The government is responsible for providing sustainable and integrated waste management facilities and systems from urban to rural areas. It also should agree with industry on building facilities and systems to process plastic waste.

Veryl Hasan is a lecturer in the Faculty of Fisheries and Marine, Department of Aquaculture of Airlangga University, Surabaya. Indonesia. His research is focused on Ichthyology and Fish Ecology. Dr. Hasan declares he has no conflict of interest and is not receiving specific funding.

This article has been republished for World Environment Day 2023. It was originally published on February 9, 2023.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.