We use cookies to improve your experience with Monash. For an optimal experience, we recommend you enable all cookies; alternatively, you can customise which cookies you’re happy for us to use. You may withdraw your consent at any time. To learn more, view our Website Terms and Conditions and Data Protection and Privacy Procedure.

The wrap on food waste

Published on June 15, 2022As the world faces a growing food crisis, scientists are investigating how we can waste less of it.

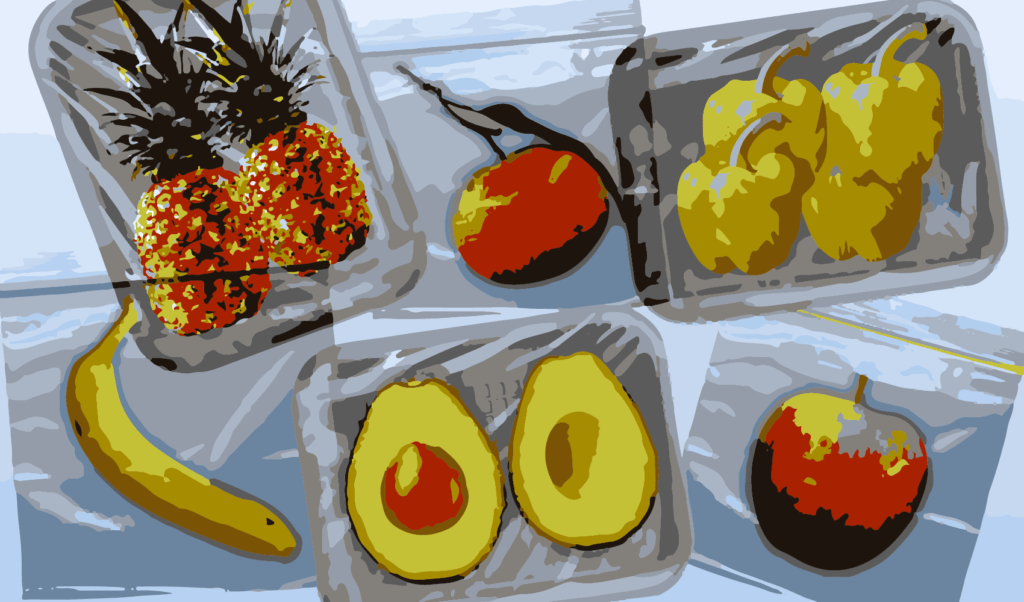

Food waste and plastic are intertwined problems. : Michael Joiner, 360info CC BY 4.0

Food waste and plastic are intertwined problems. : Michael Joiner, 360info CC BY 4.0

As the world faces a growing food crisis, scientists are investigating how we can waste less of it.

The world is in the midst of a food crisis. The price of wheat has doubled since January. The prices of other foods, such as bananas, corn and soybeans, are at all-time highs. Malaysia has begun stockpiling chicken. More than 100 countries have hungrier populations in 2021 than they did in 2000.

Yet the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization estimates some 30 percent of all food grown never makes it to the dinner plate, so the resources used to grow it – water, land, minerals – were wasted. William Gibson’s famous line about the future could just as easily be applied to food: it’s here, it’s just not very evenly distributed.

Part of that distribution relies on efficient supply chains and suitable packaging to transport food from where it’s grown to where it’s eaten. In developing economies, most food loss occurs between the farm gate and the market, with poor storage, packaging and unconnected supply chains contributing to food spoilage. In developed economies, food waste happens between the market and the dinner table, with consumers buying too much and not properly storing their supplies.

Long viewed as an environmental villain, plastic packaging can do much to stop food waste. In many cases, the resources used to grow the food far outstrip the resources used to create packaging. Perhaps surprisingly, that means food waste can be a bigger villain than plastic waste. But the situation is complex. Just as different foods require different conditions to grow, so their packaging and protection is specific to the food. The solutions vary food by food across the world.

REALITY CHECK

Per capita food waste by consumers in Europe and North America is 95 to 115 kilograms a year, while in sub-Saharan Africa and South and Southeast Asia it is 6 to 11 kilograms a year.

With the global population predicted to rise from seven billion to nine billion by 2050, the supply of food will need to increase by 77 percent compared with 2007.

Global plastic resin production grew from 1.7 million tonnes a year in the 1950s to approximately 348 million tonnes in 2017. Less than 10 percent of plastic has ever been recycled.

BIG IDEAS

Quote attributable to Helén Williams, Karlstad University:

“Reducing food packaging without analysing the effects on food waste may create an environmental and social mess. Food and its packaging need to be considered as a unit.”

Quote attributable to Simon Lockrey, RMIT University:

“It does not just involve packaging design and manufacture; end-of-life systems also need to be ready for change, or else design efforts will be for naught. Also, consumers will need education, so they can recycle, reuse and compost effectively.”

Quote attributable to Svenja Kloß, Albstadt-Sigmaringen University:

“Both indicators and sensors could reduce food waste and increase consumer safety. They could be a useful addition to the traditional best-before date and may even replace it under certain circumstances.”

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: In the story “The wrap on food waste” sent at: 16/06/2022 15:39.

This is a corrected repeat.