Online sexual violence can be deadly. A landmark new Indonesian law is a promising start, but doesn’t go far enough to stamp it out.

Victims of image abuse suffer on many fronts. : Phone woman screen time by r. nial bradshaw is available in https://bit.ly/3sFTeXM CC BY 2.0 DEED

Victims of image abuse suffer on many fronts. : Phone woman screen time by r. nial bradshaw is available in https://bit.ly/3sFTeXM CC BY 2.0 DEED

Online sexual violence can be deadly. A landmark new Indonesian law is a promising start, but doesn’t go far enough to stamp it out.

A few weeks ago, a 16-year-old Indonesian girl committed suicide after nude images, allegedly taken by an ex-boyfriend, were spread on social media.

The teenager, from North Central Timor Regency in East Nusa Tenggara, had felt “embarrassed” after the images were spread to her school friends, police said.

The case comes about 18 months after Indonesia introduced landmark legislation aimed at protecting the rights of women: The Sexual Violence Criminal Law No. 12 of 2022.

This law had wide scope, from catcalling, sexual violence in digital spaces, to rape and sexual exploitation; from marital rape (in order to strengthen the Domestic Violence Elimination Law No 23 of 2004) to sexual violence committed by corporations.

Among other things, the law sets out nine kinds of sexual abuse, including sexual violence committed in digital spaces.

Rates of online gender-based violence have risen significantly since COVID hit, as the pandemic increased dependency on online communication. Indonesia’s National Commission on Violence against Women received 940 reports in 2020, a nearly 400 percent increase from 2019.

The abuse suffered by the teen victim in East Nusa Tenggara – non-consensual sharing of sexual images – is one common type of online gender-based abuse, commonly called ‘revenge porn’, and is overwhelmingly targeted at women, by men.

This kind of abuse is on the rise – 70 percent of online gender-based violence involves images, according to the Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE).

Typically, the victim and perpetrator know each other and were once dating, or married. The perpetrator distributes, or threatens to distribute, non-consensual intimate content involving the victim, created during the relationship.

Sometimes, the perpetrator uses ‘deep fake’ images — where an artificial image is created of the victim. This form of image-based sexual abuse can also be used to blackmail the victim.

Image-based sexual abuse can also take place where the victim and perpetrator have no personal relationship, such as images taken without the victim’s knowledge (“up-skirting”).

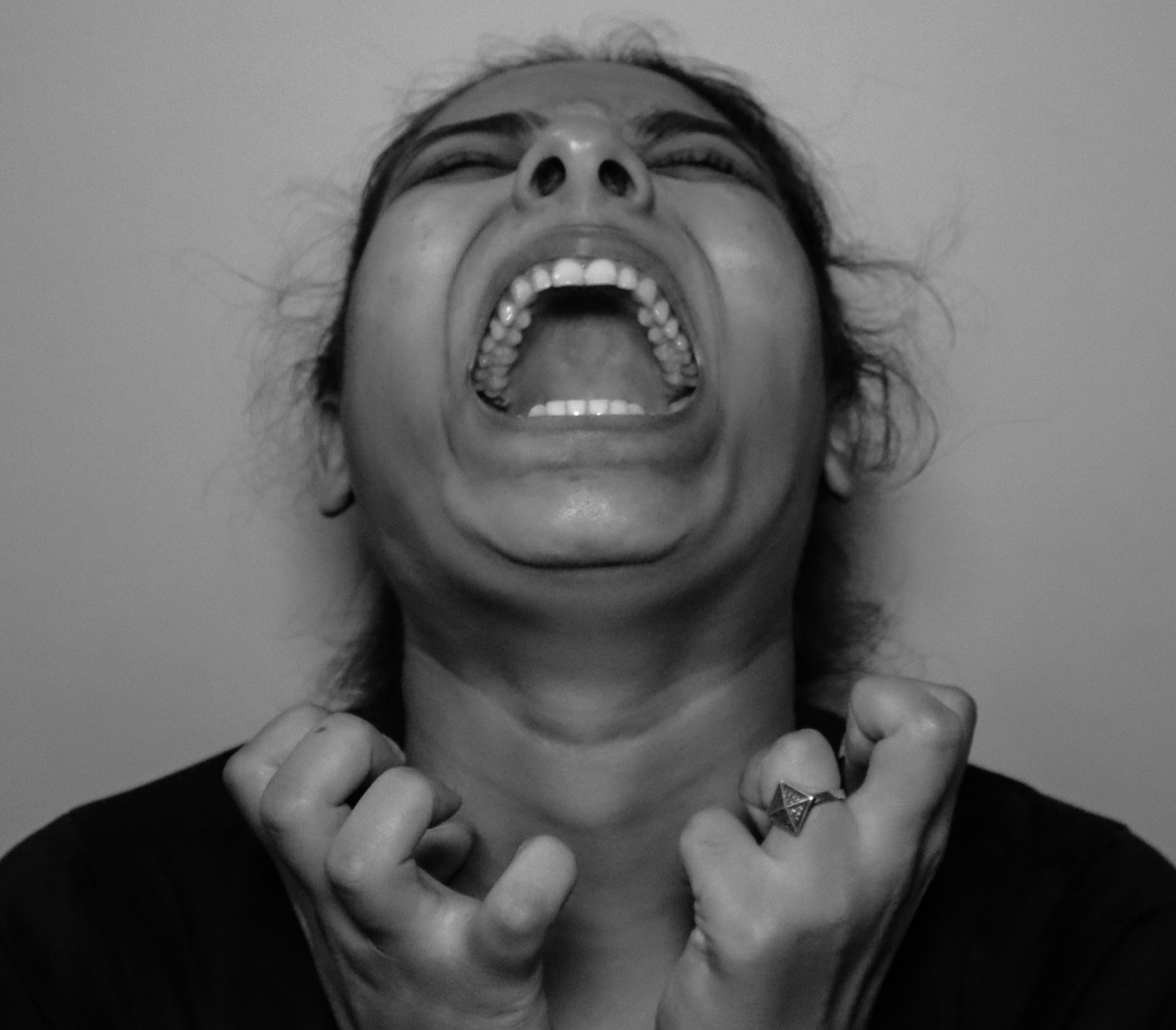

Non-consensual sharing of intimate images can cause trauma and extreme distress in victims.

One account of this crime, published in Konde, describes how a woman in her early 20s was harassed via WhatsApp and texts to her smartphone, with threats to share images of her in bed. “This situation made her feel stupid and helpless,” according to the report.

Image-based sexual abuse holds “great destructive power … because these threats can be sent directly … and can be carried out at any time’’. Victims can experience feelings of shame and loss of control “because of how hard it is to fully eradicate a piece of content from the internet when it has been shared.”

Victims can also suffer financial hardship and social ostracisation such as isolation and ‘social rupture’.

They cut connections with their family and friends, withdraw from social media and from society. This shut down of communication then affects the victim’s professional life. They often experience obstacles in returning to work which in turn can affect their financial wellbeing.

Socially, the victim often suffers because she is embarrassed, or afraid that the public, her family or new partner will recognise her photos or videos once they’ve been spread. As a result, the victim sometimes limits her interactions with other people, isolating herself further at the very time she needs support.

In the case described in Konde, the victim sought help from people closest to her and service providers. However, not all victims can access this assistance. The teenager in East Nusa Tenggara is one example of how this abuse can turn deadly. Similarly, a woman in Egypt committed suicide after her husband threatened to share a nude video unless she relinquished her rights to money and furniture in their divorce.

The Sexual Violence Crime Law is a crucial step forward. Its presence is an important point of resistance to digital-based sexual violence in Indonesia. Several regulations related to digital content and sexual violence, for example the Information and Electronic Transactions Law and the Personal Data Protection Law, still do not accommodate protection for victims of digital-based sexual violence.

When the Electronic Transactions Law is implemented for a digital-based sexual violence case, especially if combined with the Anti-Pornography and Porno-action Law, the victim will experience criminalisation because they are considered to have contributed to creating and disseminating it. But it does not go far enough in creating mechanisms to actually hold perpetrators accountable.

Other challenges remain.

Many police still think sexual violence should involve actual touching. Digital expertise is also needed to track down offenders online. And coordination between police and social media platforms and search engines to provide evidence is not always smooth. There are potential conflicts for platform providers and search engine managers when it comes to privacy.

There also is no mechanism for imposing restraining orders on perpetrators. In cases of digital stalking or “revenge porn”, how can we ensure the perpetrator does not attempt to access the victim’s social media account?

A judge in Pandeglang District Court, Banten, Indonesia, banned a man from the internet for eight years. The sentence begged the question of proper enforcement. How can authorities ensure he will not access the internet during the specified time? In the end, the man and his lawyer were successful in having the sentence revoked on appeal.

Perpetrators of image-based abuse are also hard to catch because many share images anonymously. Especially with “deep fakes”, law enforcement and prosecutors may not be able to tie the non-consensual images to their creators. In Indonesia, as in many countries, the onus is often placed on the victim to produce evidence of the content’s creation or attribution.

Victims of online-based gender violence need family and community support, not blame. Some victims of digital sexual violence fear being stigmatised for appearing in nude content, which may impact their willingness to report these crimes or otherwise seek help.

It is important for the Indonesian government to build reporting mechanisms that are more victim-friendly and less victim-blaming. The public also needs education to not redistribute the digital content which are containing sexual violence.

Lawmakers and policymakers can also work to introduce ’rights to be forgotten’, the mechanisms to remove intimate content that is distributed non-consensually, based on a victim’s request. They also could impose laws allowing victims to seek restraining orders on perpetrators, as well as preventing perpetrators from stalking their victims or committing other repeated violence against the victims.

Lidwina Inge Nurtjahyo is a lecturer and researcher in the Faculty of Law University of Indonesia. She has developed a women and children legal clinic at the University of Indonesia.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.