For years, sperm donors believed their identity would remain secret, but the explosion of online DNA databases changed everything.

Commercially available DNA tests have made it easier than ever for donor-conceived individuals (here, represented by a stock image) to track down their donor parent. : Pexels: Julia M Cameron CCBY4.0

Commercially available DNA tests have made it easier than ever for donor-conceived individuals (here, represented by a stock image) to track down their donor parent. : Pexels: Julia M Cameron CCBY4.0

For years, sperm donors believed their identity would remain secret, but the explosion of online DNA databases changed everything.

When I was a sperm donor in the mid-1980s in Australia, I was told my identity would be kept private. Forever.

But it wasn’t. Victoria, where I live, retrospectively overturned its donor anonymity laws in 2017, meaning children could identify, and potentially try to contact their biological father (even those who’d been promised anonymity.)

Today, almost four decades after I first became a sperm donor, anonymity is probably impossible.

My seven biological children born from my donations have been able to know who I am once they turned 18, and to get in touch if they wish.

So far, four have made contact.

It has been an interesting experience — for them and for me — meeting a person who shares half of your DNA, but whom you have never met.

Some of my donor-conceived offspring wish for, and have developed, ongoing connections with me and some of their siblings. Some want to stay at arm’s length, just wanting to know medical history and ancestry information. It is important they are the ones to make those choices.

For me there is the challenge of knowing I have seven biological children in addition to the two children from my marriage. I had no idea of these potential complications when I signed up to be a donor all those years ago.

In a world where DNA databases through commercially available genealogy tracing products are increasingly popular, children can bypass the ‘official’ channels and track down their donor dad with ease.

This raises questions about what happens to officially mandated channels for making those connections and the benefits and challenges of these commercially available DNA databases.

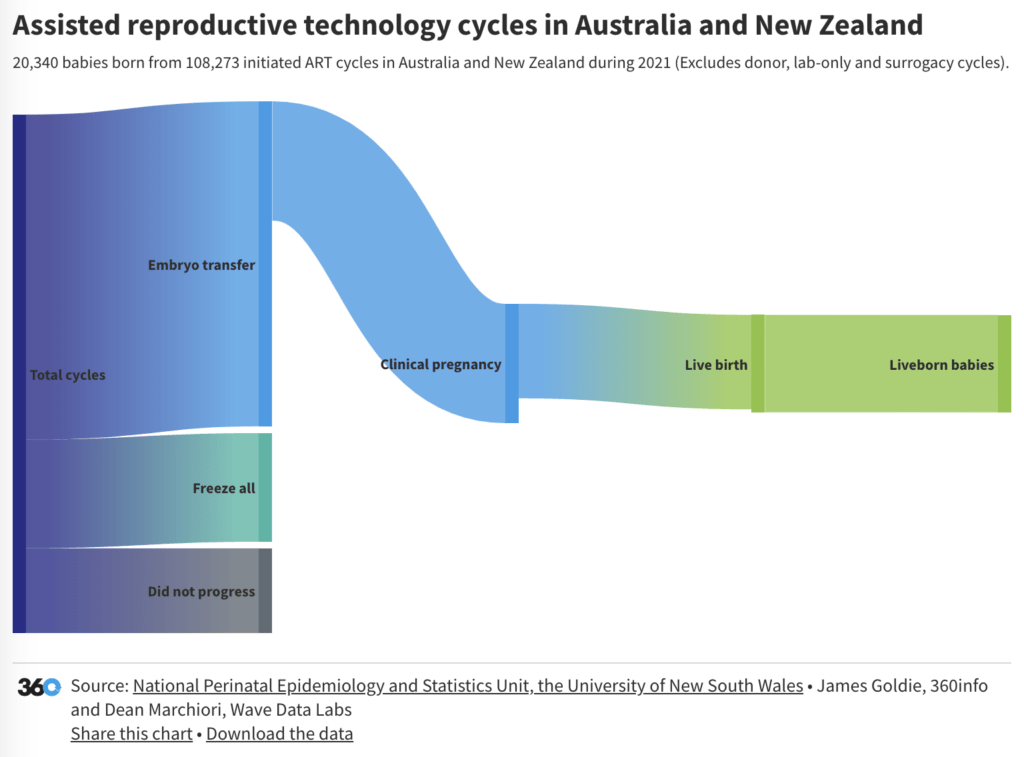

Donor conception involves using donated sperm or eggs to enable those who cannot otherwise have children to do so: infertile heterosexual couples, same-sex couples and single mothers by choice. Conception with the use of donated sperm (or eggs, or embryos) is commonly used in Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) techniques such as IVF, which is big business across the globe.

Australia, along with India and the UK, was at the forefront of developing ART technology in the 1970s and ‘80s. Laws and regulations around ART lagged behind the medical and scientific advances.

The Australian state of Victoria was the first in the world to enact legislation to regulate ART, in 1984.

Then, 32 years later, Victoria again led the world in retrospectively removing anonymity from all sperm and egg donors, regardless of when they had donated.

The chief driver for that legislation was lobbying by donor-conceived people who wanted to be able to know the identity of all of their biological parents.

As a donor, after some consideration and consultation with family, I felt OK with my identity being revealed to my biological children.

But many former sperm donors were not happy with the change to the rules they had signed up for.

Other states in Australia including Queensland, Western Australia and South Australia are now following Victoria’s lead in enabling all donor-conceived people to know the identity of their biological parent.

Alongside those laws sit donor-linking registers and mechanisms for children and donors to find and connect with their biological family members.

There’s a complex web of state legislation, clinic-based services and informal linking mechanisms available, but Victoria has the most experience in operating these services, through the donor-linking registry of the Victorian Reproductive Treatment Authority.

Over the last two decades, an alternative to those ‘official’ channels has emerged: the DNA database search services such as AncestryDNA, 23andMe, GEDmatch, and MyHeritage. With a simple DNA swab and a few clicks to set up an account, these services offer donor-conceived people, donors and others the ability to find and connect with genetic relatives.

The popularity of these services has grown exponentially since Ancestry.com launched in Australia in 2006. One estimate is that more than 30 million people have signed up to these sites. If it continues, that trend could quickly lead to DNA databases containing data on the genetic makeup of more than 100 million people.

The rise of these direct-to-consumer genetic testing services has challenged the rules and expectations of the ART industry worldwide — an industry that had once emphasised and practised anonymity of sperm and donors.

But there are benefits.

Some donor-conceived people, especially those conceived in the era of attempted donor anonymity, may distrust the ‘official’ channels for finding genetic family. DNA databases offer them agency, and the practical means to find their biological family.

For those conceived through informal donor arrangements rather than clinics, the DNA databases allow them to track down donors whose details have not been recorded in official state registers.

But these commercial DNA databases also present legal and ethical challenges.

It is now possible for donor-conceived individuals younger than the legally specified age — 18 in many jurisdictions, and 16 in some — to sidestep official channels and trace and contact their biological donor parent.

DNA database users may also learn of the existence of biological half-siblings — who haven’t prepared or consented to be identified. (That said, some research has found that donor-conceived young adults report primarily positive experiences with finding same-donor peers/siblings.)

They may also inadvertently reveal an individual has no genetic link to their social parent — which could have significant consequences where the child has not been told they are donor-conceived.

And while official donor-linking services typically offer free expert counselling and other support services, self-service DNA databases typically offer limited support for dealing with “DNA surprises”.

Direct-to-consumer genetic testing services aren’t going anywhere — and researchers have argued that their ramifications and potential psychosocial consequences should be made clearer to all parties involved.

Donors should be explicitly informed about the implications of these databases, as the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology Working Group on Reproductive Donation has argued. Donors also should be made aware their genetic identity might be revealed at any point through DNA testing — even if they were granted anonymity by the legislation of their home country.

Similarly, in jurisdictions where anonymity is still mandated by legislation, donors should also be informed this legislation may in the future change.

Donors, like me, in Australia could not have anticipated such retrospective legislative change.

That experience also puts donors in other jurisdictions on notice that the same thing could happen to them.

Ultimately, while ethicists might debate whose rights should prevail — donors wanting to retain anonymity or donor-conceived people wanting to know their origins — the fact is that recipient parents and donors are all already sharing their genetic information, along with methods to identify genetic links, in vast online communities.

In Australia, whether it be DNA databases or ‘official’ linking registries, donor-conceived people now have choices in how they can find their biological family.

Lawmakers need to anticipate that such contact between donors and their offspring will continue to happen and that regulated arrangements will be increasingly bypassed. Policy makers would do well to recognise this — and respond accordingly.

The genie is out of the bottle, and there’s no going back. The age of donor anonymity is long gone.

Ian Smith is a PhD candidate in the La Trobe University Law School. He is researching the Victorian donor-conception law reforms. Ian was a sperm donor in Victoria in 1986/7.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.