Medical cannabis has been trumpeted in the media as a panacea for all manner of pain. But scientific evidence that it works is lacking.

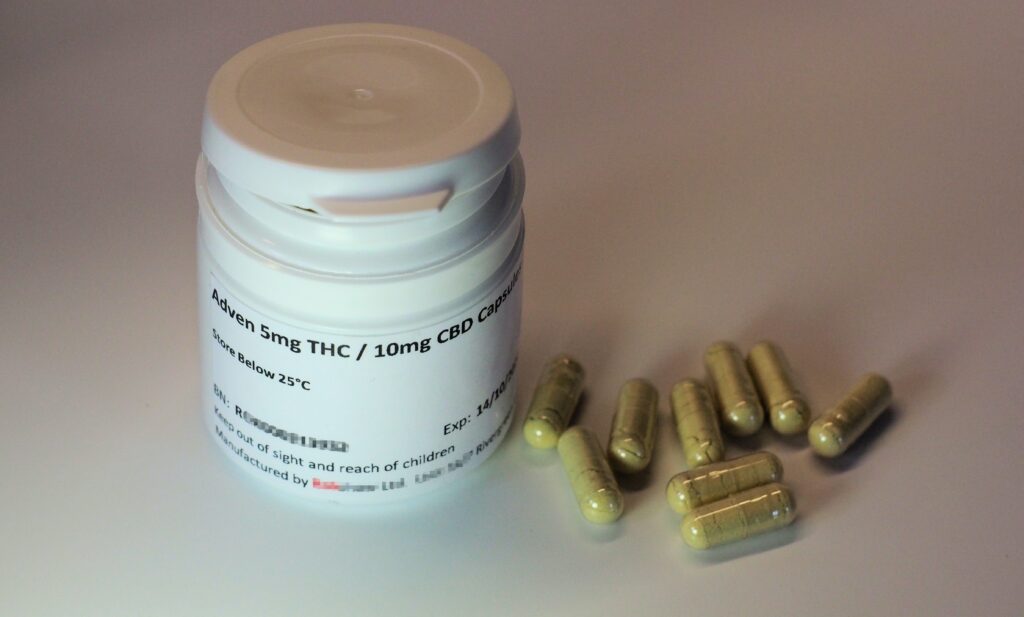

Legally prescribed Cannabis medication capsules in the UK. : Photo by Stephen Cobb on Unsplash Unsplash Licence

Legally prescribed Cannabis medication capsules in the UK. : Photo by Stephen Cobb on Unsplash Unsplash Licence

Medical cannabis has been trumpeted in the media as a panacea for all manner of pain. But scientific evidence that it works is lacking.

Of the hundreds of thousands of applications to Australia’s medicines regulator for special access to medical cannabis, chronic pain is the top reason given.

With so many seeking access to medical cannabinoids for pain, you’d expect strong evidence for its effectiveness as a treatment. But such evidence is hard to find when looking at clinical studies and independent, high quality, ‘systematic’ reviews of well conducted, randomised, controlled trials.

The reviews have consistently found medical cannabinoids have only a small effect; for most people in the trials, their pain is not reduced. Just one in 24 people across all the reviewed trials experience a clinically meaningful reduction in pain after using medical cannabis.

This means that even though a small number of people might have reduced pain, for most people, medical cannabinoids do not provide a clinically meaningful change in their pain, or at least will not provide a greater effect than a placebo. Those people who do have a good result often have very specific types of pain, for example pain related to multiple sclerosis.

Despite the lack of evidence, Australians continue to pay hundreds or thousands of dollars a month to access medicines that are yet to be approved by the regulator, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA).

Although there is no agreed definition of what medical cannabinoids are, they are generally understood to be medicines that are made from cannabis plant material, or synthetically manufactured substances that have similar therapeutic effects to the main active parts of the cannabis plant, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabidiol (commonly called THC) and cannabidiol (CBD).

Most of the cannabinoid products available in Australia are not approved by the TGA. Instead, it provides access to unapproved products under a special access scheme, meaning an exemption is made for someone to access a product even though it has not been registered or proven to work. During the product registration process there is an assessment of whether a product is effective and of its safety profile.

Products accessed under an exemption are still required to have known ingredients, but they have not been required to conduct clinical trials to show that they work.

Medical cannabis remains expensive in Australia because it has not been subsidised under the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme — which requires medicines being assessed to be both effective and cost effective. No medical cannabinoid products have been assessed to meet this standard of evidence for the treatment of pain in Australia. One product was assessed for multiple sclerosis, but evidence on whether it was safe and better than the standard treatment was insufficient to support subsidising the medicine in Australia.

So even though the product is approved in Australia, it is not subsidised. The only medical cannabinoid product that is both registered and subsidised in Australia is cannabidiol for the treatment of a rare form of childhood epilepsy.

There has been a lot of interest in CBD as a single ingredient for pain. CBD is often preferred because it does not cause the same ‘high’ and sedation as THC. However, there is not clear evidence that CBD works for pain, with few studies examining the effects of CBD alone. Those that have examined CBD as a single ingredient have not provided evidence that it works for pain.

Given researchers have conducted a large number of trials of medical cannabinoids for pain, and a large number of systematic reviews summarising the evidence, the issue is not necessarily a lack of studies, but a lack of evidence demonstrating the benefits outweigh the potential harms.

A recent Cochrane review concluded “The potential benefits of cannabis‐based medicine in chronic neuropathic pain might be outweighed by their potential harms.” Nevertheless, it is possible that further studies conducted in specific patient populations or with specific clinical conditions may identify conditions or patient groups where the benefits are greater.

Meanwhile, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) says it views medical cannabis as an area for research, as opposed to clinical practice, while evidence accumulates. Similarly, the Faculty of Pain Medicine, a specialist medical college for the treatment of pain in Australia, says medical cannabis should not be used outside clinical trials.

Yet many people, having read articles in popular media, have unrealistic expectations about how well cannabinoids work for the treatment of pain.

With time, further robust clinical trials may provide the required evidence for cannabinoids to become widely available as a registered, subsidised medicines. If that happens, it would save patients money, and provide clinicians clearer guidance about the place of medical cannabinoids in pain treatment. In the meantime, being part of a clinical trial is one way to access medical cannabis for pain and contribute to new evidence.

Suzanne Nielsen is a professor and the deputy director of the Monash Addiction Research Centre. She has been a registered pharmacist for over 20 years, and has been involved in multiple reviews on the evidence for the use of medical cannabinoids, including independent reviews commissioned by the Therapeutic Goods Administration.

In the past, Professor Nielsen has received funds from Seqirus to study opioid-related harms, and was a named investigator on a clinical trial of a treatment for opioid dependence (no funding received), both unrelated to the current article. She is current funded through a National Health and Medical Research Council Fellowship (#1163961).

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.