‘Women do not have to go through hell just to birth their babies’

In much of the world, myths regarding childbirth mean women experience more pain than they could. Education is key.

Mofoluwake Jones holds her daughter. Supplied/CC4.0

Mofoluwake Jones holds her daughter. Supplied/CC4.0

In much of the world, myths regarding childbirth mean women experience more pain than they could. Education is key.

Mofoluwake Jones has two children, but their entries into the world could not be more different. Mofoluwake’s first child was born in Nigeria, a nation with a cultural tradition of women suffering silently in childbirth.

“I guess that’s how we were all programmed to see labour,” says Mofoluwake. “It seems we are yet to adopt the mindset that women do not have to go through hell just to birth their babies.”

Mofoluwake’s second baby was born five years later, by which time she was living in Canada. “All the health workers were courteous, they took their time to explain what they needed to do on me and why. For each cervix examination, my consent was sought before they went ahead to examine me,” she says.

“The moment I got to the hospital, they had started asking if I had thought about my pain management plan, they explained the different options available and gave me a booklet on … the risks associated with each and benefit.”

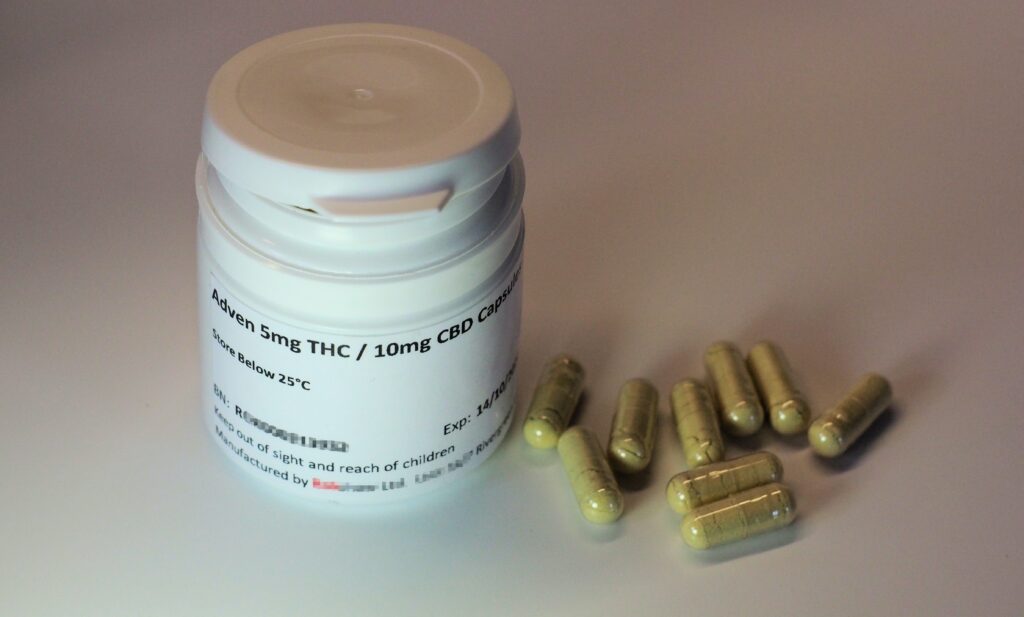

While labour pain is expected, it can be managed to reduce risks and provide optimal comfort to the mother. But in many developing countries, pain relief during childbirth is underutilised due to cultural myths and taboos.

In some cultures, the woman is expected to scream and cry uncontrollably, while in others, the woman may not express much distress in her labour. Some women refuse to accept pain relief during labour because they see the pain as natural. Some women believe they should not take pain medications in case it causes harm to the baby.

In the Christian faith, the pain of labour pain is referenced in the Bible as God’s punishment on women for being disobedient (Genesis 3:16). Labour pain is therefore considered normal by many women and midwives.

In such cultures, as girls approach womanhood, they are taught about the suffering and pain of childbirth so they are prepared for it.

In Nigeria, among the Hausa people of northern Nigeria, there is great social pressure not to show any sign of pain. Going through labour quietly and without any pain relief indicates virtue. The Fulani girls from Nigeria are taught from an early age how shameful it is to show fear or cry during childbirth. The Bonny people of southern Nigeria are taught to believe that when a woman endures pain during childbirth, it shows how strong and capable she is as a woman. She is made to believe that no amount of screaming and shouting can reduce the pain, so it is better to bear it in silence.

The perception of health professionals, especially nurses and midwives, also influences the use of pain relief.

Despite pain relief being safe for mother and child, a study by British obstetrician Mary McCauley and colleagues found more than half of all health-care professionals in Ethiopia were concerned about the effect of pain relief on the baby, mother and the labour process. Previous studies have found that these concerns are shared by women as well, even when they agree the pain should be relieved. Many health-care professionals in developing economies do not provide women with options for pain management during labour other than support from family. Neither is it included in antenatal classes.

A study in south-eastern Nigeria revealed only 39.5 percent of expectant mothers were aware of labour pain relief. Similar results were found in northern Nigeria. Lack of awareness is the principal obstacle to greater use of pain relief during childbirth.

If the obstetrician discusses the options, benefits and risks associated with pain relief with the mother, irrespective of her beliefs, she is more likely to have a better birth experience, with optimal labour pain control, in line with her values.

When pregnant women in developing economies are made aware of pain relief in antenatal discussions, it will allow for increased use. Individual preferences and fears women may have regarding labour pain relief can be addressed using client-centred education in antenatal care, dispelling myths that may persist.

For Mofoluwake Jones, having discussed her options thoroughly with the medical staff in Canada, she chose an epidural for her second baby. A birth consultant coached her through the pushing stage, helping her manage her energy and providing advice on the best times to push.

“It was such a beautiful birth experience. I was in the hospital for about three days and the way I was treated — with respect and made to understand that labour does not have to be hell — made me have a paradigm shift which I can only hope and pray my country, Nigeria adopts with time.”

Deborah Tolulope Esan (RN, RM, RPHN, BNSc, MPH, PhD) is an associate professor of public health nursing/community health nursing at Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria. Mofoluwake Jones is her sister.

Blessed Obem Oyama (RN, RM, BNSc) is a graduate student, at the department of nursing science, Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: In the story “Pain treatment myths” sent at: 09/12/2022 16:53.

This is a corrected repeat.