Arms conference puts trillion-dollar industry under the spotlight

The global trade in arms is worth more than two trillion dollars. A UN conference this week aims to bring more oversight to this deadly industry.

The international trade in submarines is particularly fraught for the Australians. : LSA Ian Gollop, Commonwealth of Australia CC 2.0

The international trade in submarines is particularly fraught for the Australians. : LSA Ian Gollop, Commonwealth of Australia CC 2.0

The global trade in arms is worth more than two trillion dollars. A UN conference this week aims to bring more oversight to this deadly industry.

Australia is among the five largest importers of arms, globally. In 2021, Australia spent the equivalent of US$1.235 billion on the legal import of weaponry, according to an assessment by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, making the peaceful nation the world’s number one importer of deadly capability.

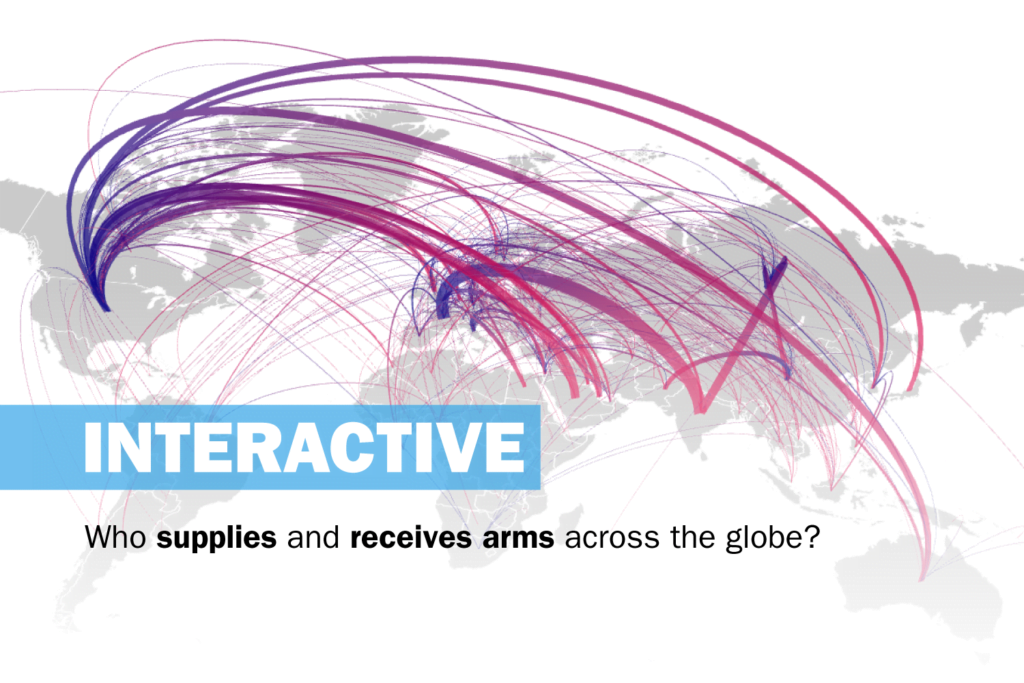

In exercising its sovereign right and responsibility to provide security, Australia can legitimately acquire and employ a range of weaponry. These include weapons designed for warfare, such as submarines, battle tanks, armoured combat vehicles, large-calibre artillery systems, combat aircraft, attack helicopters, warships, missiles and missile launchers. They also include small arms and light weapons. Arms are traded around the world in eye-watering numbers. In 2021, world military expenditure reportedly reached US$2.113 trillion. The constant demand for weapons has resulted in a vast global arms economy.

The United States, China, India, the United Kingdom and Russia were the five largest spenders on their military in 2021, together accounting for 62 percent of expenditure. In the period 2017-21, the five largest exporters were the US, Russia, France, China and Germany, accounting together for 77 per cent of all arms exports. Apart from Australia, the five largest importers of arms during that period were India, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and China, collectively responsible for 38 per cent of total global arms imports.

In addition to the so-called ‘white market’ concerned with legitimate trade in arms, a large and profitable black market has developed for official and unofficial ‘non-state actors’ to avoid compliance with international and domestic weapons restrictions. The illicit trade in arms contributes to, amongst other things, armed conflict, destabilisation of governments, refugee crises, organised crime and terrorism, and it significantly impacts on civilians in war-troubled areas.

Weapons enter the illicit realm through their ‘diversion’, that is, through their transfer from an authorised to an unauthorised user. Diversion can happen through weak inventory controls, weak or unenforced regulation, corruption, negligence, theft and so on, and it can occur at various points in the supply chain. Small arms and weapons, and their ammunition and parts, are particularly prone to diversion, largely due to their portability, ending up in the hands of terrorists, criminals, armed groups and other illegal users. Trade in small arms is the least transparent of all weapon systems. Experts estimate that hundreds of millions of small weapons are held around the world, approximately three quarters of which are in civilian hands.

In the 1990s, a process began towards creating an international treaty to regulate the arms trade culminating in the adoption of the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) by the UN General Assembly on 2 April 2013. As of March 2022, 111 nations, including Australia, are party to this treaty, 30 are signatories (that are not yet States Parties), and 54 nations have not yet joined the Treaty. Notably, the United States and Russia (the world’s largest exporters of arms) and India, Saudi Arabia and Egypt (the world’s largest importers of arms) are among the absentees.

The main objective of the ATT is not to prohibit the legitimate trade in conventional arms, rather it is to establish standards for regulating the trade, and prevent and eradicate the illicit trade. It applies only to the arms mentioned above when they are exported, imported, in transit, trans-shipment or brokered, collectively known as ‘transfer’ in the treaty. The ATT assigns regulation of ammunition, munition and parts to individual nations.

The ATT prohibits transfer of arms if it would violate a country’s obligations under the United Nations Security Council, or if the transfer would violate other international agreements, or if states know that the arms would be used in genocide, crimes against humanity, or other war crimes. Otherwise, countries must make their own assessment as to whether a transfer would undermine peace and security. This risk assessment is consonant with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in particular SDG 16 concerning peace, justice and strong institutions, as the ATT is also concerned with promoting international peace, security and stability.

Although the ATT represents a significant step in regulating arms trade, a number of factors leave an undesirable level of interpretative freedom to individual nations. For example, inadequate treatment of ammunition/munitions and parts, silence on non-commercial transfers, and largely soft, and at times “extremely broad” language. Failure to address criminal responsibility and accountability of various actors involved in the arms trade, and elasticity of state self-regulation have the potential to further curtail the treaty’s effectiveness.

To increase responsibility, accountability and transparency, parties must report to the secretariat on their measures to implement this treaty. They may exclude commercially sensitive or national security information.

States parties’ reports are an essential tool for understanding, monitoring and evaluating the ATT’s implementation. However, the ATT reporting system has not lived up to its potential. The reporting exceptions create room to evade obligations. Reporting has been characterised by poor compliance and limited information.

This week, the Conference of States Parties to the ATT is scheduled to take place in Geneva, Switzerland. The issue of ATT reporting, together with the issues of implementation and greater acceptance, is included in the agenda. Neither the Department of Foreign Affairs nor the Department of Defence could confirm whether Australia would be represented at a ministerial level at the conference.

While there is the consensus within the majority of the UN membership that the ATT is useful and worth preserving, not all states approve of the content of the most substantive provisions of this treaty. What is undeniable is that the ATT’s success is subject to the universal adoption and implementation. It is debatable whether this will eventuate, given the legacy of many decades of inadequate control of arms, and instances of prevailing economic interests over human security. But unless universal adoption comes, the ATT is likely to be viewed merely as a noble idea and somewhat a paper tiger, or “much ado about nothing”, as German lawyer Marlitt Brandis has bluntly referred to it.

Unless there is more political will, transparency and cooperation on the contentious, highly sensitive and extremely serious issues of the international arms trade, the foundation cannot be laid for effectively working towards a unified consensus about international regulation of trade in conventional arms.

Jadranka Petrovic teaches and researches at the Monash Business School, Faculty of Business and Economics, Monash University. SHe declares no conflict of interest.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.