Can the ATT take any lessons from the new EU dual-use Regulation?

As nations meet to consider an international agreement on the trade in arms, lessons from the EU are ready to be learned.

A helicopter is a dual-use item. It quite simple to turn a civilian aircraft into a tool for warfare. : Jean-Pierre (Wikimedia) CC 4.0

A helicopter is a dual-use item. It quite simple to turn a civilian aircraft into a tool for warfare. : Jean-Pierre (Wikimedia) CC 4.0

As nations meet to consider an international agreement on the trade in arms, lessons from the EU are ready to be learned.

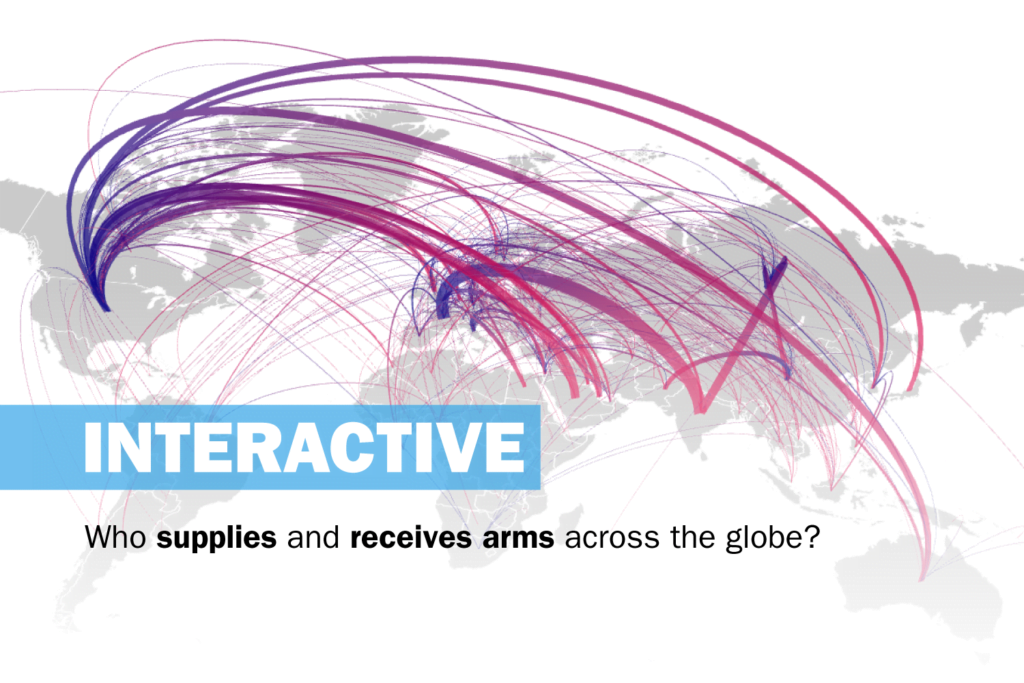

This week, the Eighth Conference of States Party to the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) will take place in Geneva. The annual conference comes just a few months after important changes in strategic trade control in Europe and the ATT negotiations could look to those changes for inspiration.

In September 2021 the European Union “recast” the regulation on the trade in dual-use items (2021/821). ‘Dual-use items’ are those with both civilian and military applications, for example GPS software or high-powered lasers. The update came after almost ten years of discussions and negotiations.

In the Recast, the EU has faced up to new technological, economic and political challenges. In particular, to emerging dual-use technologies, as well as to the intangible transfer of technology, for example, uploading sensitive information to the cloud. The Recast also mentioned and emphasised for the very first time the role of academic and research institutions that face special challenges in export control of technology.

The ATT has so far overlooked technology transfer, but it is a crucial element in developing and trading weapons and their components. Specific technology is often needed to enable or enhance military items, including weapons of mass destruction. Accordingly, the international treaty could consider widening its scope to include controls on military-related technology.

The Recast also seems to bridge some gaps that remained in the previous regulation by clarifying some definitions, for example, the definitions of export and exporter, and by introducing new ones, such as the definition (and the control) of technical assistance.

The ATT provides no definitions of the activities covered. This is understandable since it was negotiated at a global level, and not at a regional one as is the case for the EU, leading to more compromise on wording and control. But if no definitions are in the ATT, there is no reason it couldn’t include control of technical assistance and technology. The ATT could also address internal compliance programs and due diligence, that is, the policies and procedures that an organisation or company use to comply with the export regulations, for example, risk-assessments. Encouraging nations to establish their own measures in this regard could be crucial to strengthening the international coverage of conventional weapons trade.

The Recast also endeavours to increase harmonisation and transparency by encouraging states to implement paperless e-licensing systems. The ATT could also emphasise this, paving the way for a future system of sharing and pooling information. The Recast has called for nations to pursue enhanced co-operation between national authorities such as customs, but also with supranational authorities (for example, the EU Commission). This enhanced co-operation requires sharing information more regularly and with greater detail, and a shared reporting and database could aid in this regard.

The Recast has also called for an enforcement coordination mechanism; a platform to exchange best practices of national enforcement authorities. While the EU is a unique supranational organisation, other economic and regional unions (for example ASEAN) could decide to enhance co-operation on trade controls and enforcement. For this reason, it is important that ATT stresses regional co-operation.

Furthermore, setting up technical expert groups, an existing EU practice formalised in the Recast, is something the ATT can learn from. The Treaty could establish new working groups to address specific issues, for example, working groups dedicated to clarification of some aspects of the Treaty.

Finally, following the Recast, the Treaty could work towards being more precise and comprehensive. The Treaty has an opportunity to address the transfer of weapons for non-commercial reasons (for example diplomatic reasons). And it could better define what is meant by “parts and components” and include reference to dual-use items. Improved definitions of parts and components could encourage nations not to overlook an important aspect of the assembly of weapons and supply chain. While dual-use items are not included in the Treaty, the logic underpinning the Treaty should apply both to purely military parts as well as dual-use items — if a nation can easily buy a helicopter meant for peaceful uses and then acquire a weapons system from another source, it can assemble the two parts to finally obtain a fully functional military item. It’s why the Recast, to fulfill its objective, endeavours to cover all items with civil and military purposes, peaceful and non-peaceful application, and include those with the potential to violate human rights, for example cyber-surveillance items and emerging technologies. If the ATT were to stress the importance of dual-use items it would go further towards controlling all arms transfers.

The new elements of the Recast are an important step forward for arms control. The ATT could take inspiration and work towards a more efficient implementation of the control of conventional weapons.

Veronica Vella is a researcher, assistant and PhD candidate at the University of Liège. Her main area of research and expertise concerns strategic trade controls (systems, regimes and national implementation). She declares no conflict of interest.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.