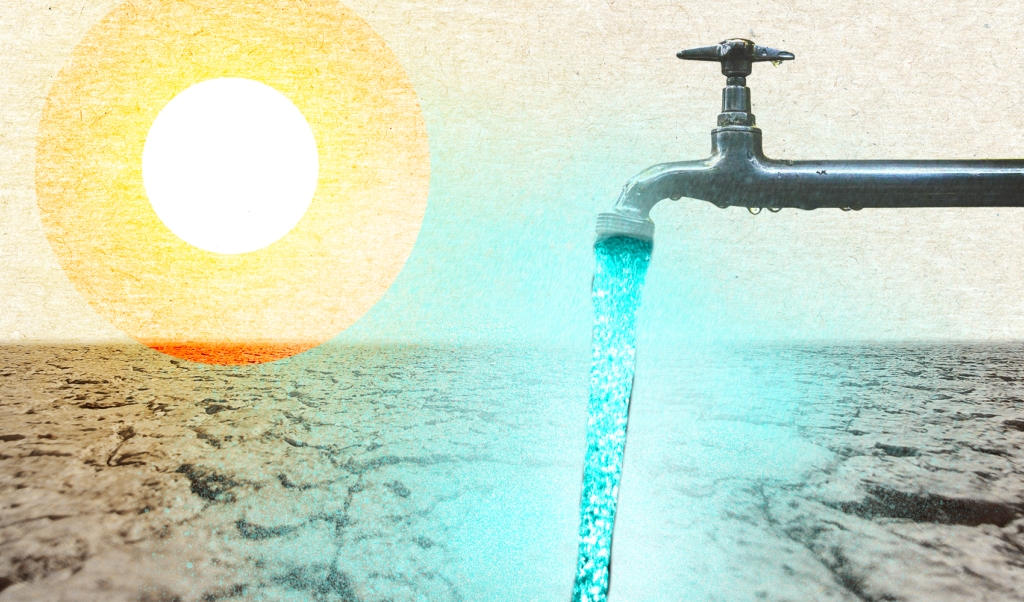

Despite being on other sides of the planet, Jakarta and Iowa are staring down similar issues around water hygiene and supply.

A rapidly urbanising Jakarta has yet to fully address its water quality issues. : Przemek Pietrak, Flickr CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

A rapidly urbanising Jakarta has yet to fully address its water quality issues. : Przemek Pietrak, Flickr CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

Despite being on other sides of the planet, Jakarta and Iowa are staring down similar issues around water hygiene and supply.

On the surface, Jakarta has little in common with the US state of Iowa.

The Indonesian capital is a coastal tropical city of over 11 million people, three times as many as temperate, landlocked Iowa. Most people in the majority Muslim city don’t eat pork. Iowa is the largest producer of pork products in the US.

Dig below the surface, however, and you find that Jakarta and Iowa face strikingly similar problems of water scarcity and water pollution.

Jakarta is crossed by 13 rivers which are clogged with garbage and heavy sediment. It makes the city more prone to flooding and allows debris to pile up. Its rivers are heavily polluted with e-coli bacteria, largely a result of untreated municipal sewage.

Several parts of Jakarta such as Pasar Minggu, Matraman and Palmerah have especially high levels of e-coli bacteria due to how close septic tanks are to groundwater sources. In these regions, many residents still bathe in the water and use it when washing clothes, despite the contamination.

Iowa also has dire pollution problems.

The Midwestern state with rolling greenery is one of the top-ranked in the US for agriculture, but this comes at the expense of water quality. The state has a water pollution crisis, caused by the excessive use of nitrogen and phosphorus in crop production.

With 90 percent of Iowa’s land designated farmland, and a population of 23 million pigs (seven times the human population), an enormous part of Iowa is geared toward agriculture and crop production.

Residents across the state face the burden of paying for expensive water treatment facilities, but those living in small rural towns pay roughly three times more for nitrate treatment systems.

People in the Des Moines area can purchase and operate more efficient nitrate removal technology to serve the city and several affluent suburbs, lowering the cost of treatment per person.

Low-income communities and people of colour are likely to live in places where higher levels of nitrate exist in polluted drinking water, presenting potentially fatal health risks such as baby blue syndrome and cancer.

This is because many smaller rural towns such as Ottumwa, Perry, Marshalltown, and Storm Lake are also home to low-income and people of colour working in large-scale farms, meat processing and packing industries.

Iowa’s nitrate pollution runoffs add approximately 50 percent to the Gulf of Mexico’s dead zone, a low oxygen area spanning over 16,000 square kilometres which can kill marine life.

Jakarta and Iowa have addressed their water issues in their own ways.

Iowa has pushed various incentives and conservation strategies relying on voluntary buy-in from farmers, but its water quality issues have hardly budged. Polk County, home of the state’s capital building, introduced a ‘batch and build’ model in which the government works directly with vetted contractors to build conservation projects on private land.

The model makes it easier for landowners to build rainscaping practices, aimed at improving water quality.

The last significant shot at regulation from the US government came in 1972 with the Clean Water Act. In the 52 years since, it has become unfit for purpose. Stricter regulation and monitoring, such of oversight of manure management plans from pig producers, would go a long way towards addressing water quality issues in these localities.

Jakarta’s residents rely on groundwater and surface water as their primary sources.

The city is facing ground subsidence as a result of excessive groundwater use. It has tried a number of approaches to fix it: restricting groundwater use, building infiltration wells for absorbing rainwater, expanding pipelines for recycled water and improving the city’s sewage system. But, as Jakarta rapidly urbanises, these efforts are not enough to fully address the water scarcity issues.

Water quality issues are only going to be properly addressed when a combination of government agencies, local communities and people from private industry can help comprehensively fix the issue.

Technology offers a number of promising ways to improve water sanitation – geospatial analytics, artificial intelligence, remote sensing and the Internet of Things (the practice of connecting objects to send and receive data) can help.

This has been effective in one of India’s most polluted lakes, Chennai’s Lake Sembakkam. AI and the Internet of Things have been used to measure and monitor water quality in the lake, using a cloud-based platform and installing sensors in the lake to track its health, issuing an alert when water quality drops to concerning levels.

This technology has given many in the community real-time information to decide how they use and conserve the water around them. The data from such monitoring, along with satellite imagery helps in other ways: it allows policy-makers and planners to better understand water quality and put plans into motion, including decisions around water purification technologies.

For Jakarta, Iowa and other regions dealing with degraded water quality, this can be a matter of life or death. Each year, the World Health Organization attributes about 2 million deaths to poor sanitation, unclean water and substandard hygiene.

The UN says over 40 percent of the world suffers from severe water stress as global demand for water exceeds supply. The release of medical waste, toxic chemicals and household waste into the atmosphere puts densely populated residential areas especially at risk of contamination.

This also harms the environment: roughly 42 percent of untreated household wastewater is discharged into rivers and ocean, causing severe pollution. Water scarcity is worsened by climate change, which affects rainfall, increases droughts and floods and reduces the availability of water.

The rate of reuse for the estimated aggregate of domestic and industrial wastewater generated stands at 11 percent. Insufficient sanitation and contaminated water sources play a large role in the spread of waterborne diseases.

Jakarta and Iowa represent the range of our water supply and sanitation crisis: one in a rising Asian power, seeking to unravel decades of river pollution, and the other in the American heartland, desperate to balance its commercial interests with community health.

As water scarcity looms as a growing issue, the challenges faced by each region represents what may become a more prevalent concern globally.

Eka Permanasari is an Associate Professor of Urban Design at Monash University Indonesia and Monash Urban Transformation Hub.

Dian Nostikasari is an Assistant Professor of Environmental Science and Sustainability at Drake University.

Derry Wijaya is an Associate Professor of data science at Monash University University.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.