Long a source of tension with its neighbours, China’s transboundary rivers are opening opportunities for regional cooperation.

Dam construction on the upper Mekong River in China (such as the Xiaowan Dam pictured here) has sparked protests from downstream neighbours. : Guillaume Lacombe/Cirad via Flickr https://bit.ly/49WYQ0b CC-BY-2.0

Dam construction on the upper Mekong River in China (such as the Xiaowan Dam pictured here) has sparked protests from downstream neighbours. : Guillaume Lacombe/Cirad via Flickr https://bit.ly/49WYQ0b CC-BY-2.0

Long a source of tension with its neighbours, China’s transboundary rivers are opening opportunities for regional cooperation.

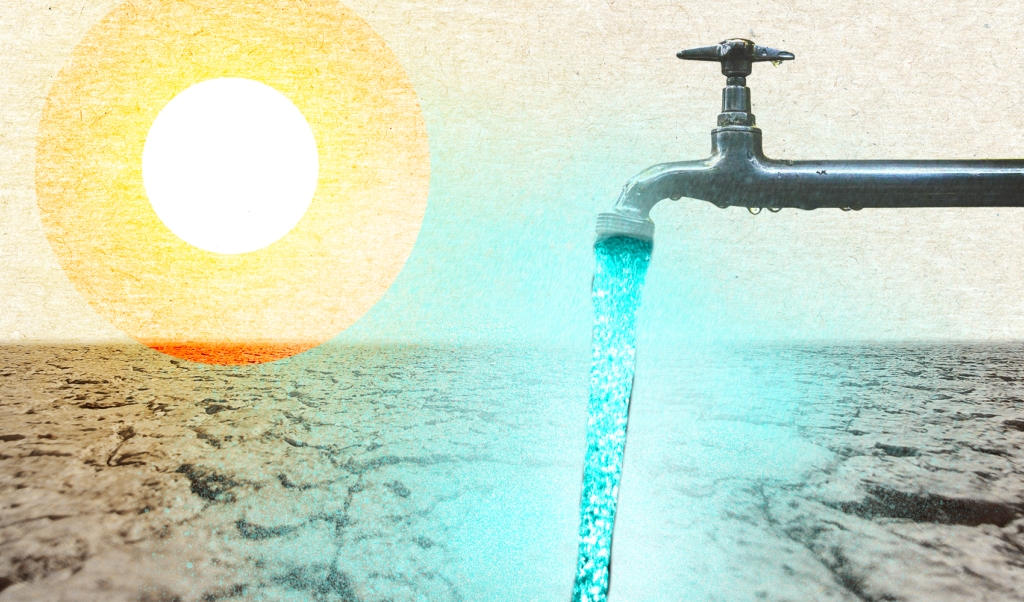

Sixteen major rivers originate in China that supply fresh water to nearly 3 billion people in 14 Asian countries – more than a third of the world’s population.

As ‘Asia’s water tower’, China has often been depicted as the upstream bully when it comes to water politics – taking what it needs for itself with little consideration for its downstream neighbours.

But with the growing connection between sustainable development and regional stability, China has an opportunity to use transboundary water management as a springboard for regional peace and cooperation.

Its success will depend not just on navigating diplomacy with many neighbouring states, but also on the unpredictable course of the US-China rivalry, as China looks to lead the world in renewable energy production.

Clean energy industries are re-adjusting their global strategies to be more in sync with international political alliances. And global mineral markets and supply chains have shifted, with China recently limiting exports of strategic rare earth minerals.

At the same time, transboundary water management and hydropower development are becoming integrated into security, political and economic negotiations among riparian states – part of an emerging “security-sustainability nexus”.

For China, this scenario presents challenges to its aspirations to create and oversee platforms for regional cooperation.

Neighbouring states are under immense pressure to bring economic growth to large populations — and to do so with clean energy.

Hydropower — harnessing the immense potential of these rivers — could be their ticket.

Since the 2016 implementation of the UNFCCC Paris Agreement, many countries in the region are facing increased pressure to phase out fossil fuels and invest in hydropower development.

Various domestic clean energy demands and complicated geopolitical positions, diplomatic histories and political cultures mean that China might make a better partner for some than for others.

Since landmark protests in Thailand 2004 against a proposed dam project in southwestern China, environmental activists and campaigners from four lower Mekong countries — Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam — have often rallied together to halt the construction of hydropower plants and dams on the upper stream Mekong (Lancang jiang in Chinese) inside China.

The protests also marked the beginning of Chinese environmental NGOs joining transnational coalitions against the construction of large dams in China.

But in recent years, due to domestic energy demands, lower Mekong region states have collaborated with China in developing hydropower projects on the river.

Some of the authoritarian states in the region, despite being highly sensitive to public protests, have allowed environmentalists and non-governmental organisations to protest against dams invested in by Chinese capital and built in neighbouring countries.

The Xayaburi dam in Laos and Sanakham dam project in Thailand are cases in point.

The situation is even more intense between China and India.

Diplomatic skirmishes related to transboundary water resource management have sometimes been referred to by observers as “water wars”. Since the establishment of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, India has frequently accused China of interfering in India-Pakistan water disputes.

A decade ago, research pointed out that China’s water diplomacy had remained underdeveloped or ineffective due to institutional constraints at both domestic and international levels.

At home, transboundary river basins, lakes, and other water resources are viewed by the Chinese state as having different economic functions such as agricultural irrigation, hydroelectric generation, fishery and shipping. As a result, they are managed on a piecemeal basis by various state agencies.

The field of transnational water management, much like other non-traditional security policy areas such as refugee and irregular migration, lacks a designated regulatory agency or unified legal-political framework. Disputes and collaborations are handled individually, depending on the specific geopolitical factors, without any cross-referencing.

In other words, what works for the Lancang-Mekong region may not be applicable to China and Kazakhstan’s collaboration on the Ili River.

At the international level, China’s involvement in multilateral water and environmental cooperation remained extremely limited until the 2000s.

China was never a member of the Mekong Committee, which ran from 1957 to 1995, and only became a ‘Dialogue Partner’ of its successor, the Mekong River Commission, in 1996. The five lower Mekong countries invited India and formed the Mekong-Gonga Cooperation in 2000. As a result, there was a diplomatic lapse in China’s governance of transnational waters.

Fast forward to 2024, and this lapse has been significantly improved. The constraints in China’s transboundary water and environmental resource management have been largely alleviated.

Although there is still no single designated state agency to coordinate China’s water diplomacy across regions, the Foreign Ministry and international-facing agencies are much more present, compared to a decade ago.

In the case of the Mekong, China finally created its own platform for international cooperation — the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation — in 2017, highlighting its upstream geopolitical standing, rather than shying away from it.

This is the second year into the second Five-Year Plan of Action on Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (2023-2027). Cooperation in transboundary water conservation and management is included on a long list of comprehensive actions planned, including high-level political-security dialogue, trade and finance, disaster prevention, transnational crime, reduction of poverty and economic development, energy and more.

In the case of the Ili, Irtysh and other rivers that connect to Central Asia waterways, China has negotiated broadly with relevant parties, including Russia.

Utilising a few key multilateral spaces, either initiated by China (Shanghai Cooperation Organization) or friendly to China (Eurasia Economic Union), China has tagged water and hydropower projects along with other types of development cooperation in the region, such as farming and rural development, transportation and infrastructure building and smart grid and energy system.

And since the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013, transboundary water and environmental resource management related to Southeast Asia, Central Asia and parts of South Asia has been quickly streamlined, repackaged and integrated into multifaceted, large-scale projects of development, clean energy and capacity building.

For example, China has been training professionals in water conservation and hydropower in many ASEAN countries directly or not linked to the Mekong river basin.

Compared with traditional intergovernmental cooperation and negotiations, these may be more incremental initiatives, but they are aimed at building new foundations and consensus for long-term cooperation.

Fengshi Wu is Associate Professor in Political Science and International Relations at the School of Social Sciences, UNSW Sydney. She is a world leading scholar in environmental politics, state-society relations and global governance with empirical focus on China and Asia.

This article was updated on 22 March 2024 to correct the spelling of Lancang.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: In the story “Water conflict” sent at: 22/03/2024 09:34.

This is a corrected repeat.