The dry weather could result in prolonged droughts and haze affecting millions across the region as it did in 2015.

Water rationing due to droughts should be expected if an El Niño hits Southeast Asia this year. : ‘Drought’ by Ivan Radic is available at https://tinyurl.com/238umdcb CC BY 2.0

Water rationing due to droughts should be expected if an El Niño hits Southeast Asia this year. : ‘Drought’ by Ivan Radic is available at https://tinyurl.com/238umdcb CC BY 2.0

The dry weather could result in prolonged droughts and haze affecting millions across the region as it did in 2015.

Malaysia and the rest of Southeast Asia face heightened risks of haze, drought and water shortages with an El Niño being declared this year.

The onset of dry conditions can typically last a year beginning in either July or August.

The region was last hit by an El Niño in 2015/16 when several countries were blanketed by a transboundary haze resulting in cancelled flights, closed schools and a sharp increase in respiratory ailments and deaths. Water rationing was also introduced due to drought.

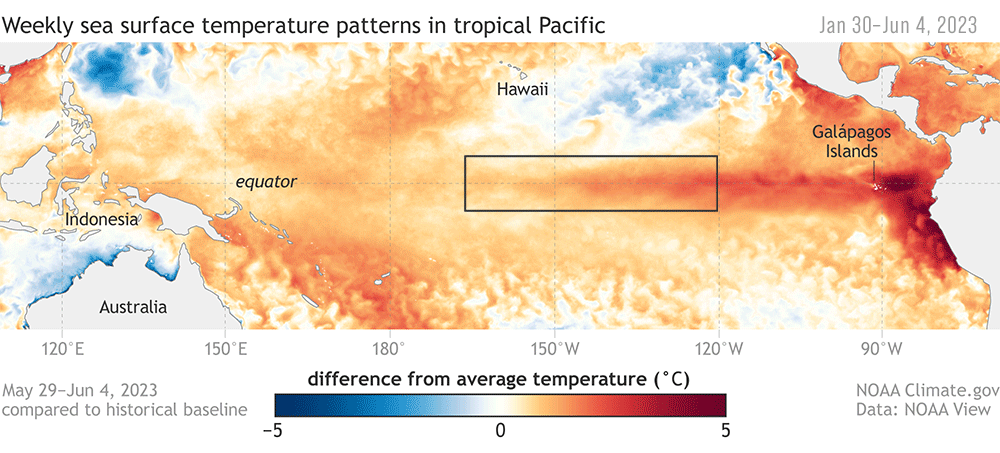

The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration agency says that an El Niño will strengthen toward the end of 2023 with a 56 percent chance of it peaking as a strong event and an 84 percent likelihood of at least a moderate event.

A strong El Niño would have considerable impact on Sumatra, Java Island, Sulawesi and southern Borneo with drier conditions from September to November. Northern Borneo and the southern Philippines could experience dry spells from December to February.

And if there is extensive open burning or forest fires in Sumatra and Kalimantan, a transboundary haze may result when the southwest monsoon sweeps the particles towards Singapore and Malaysia.

The 1997/98 El Niño event is an example of an El Niño-induced drought and transboundary haze disaster.

It is considered the most severe Southeast Asian haze event of all time, lasting three months causing billions of dollars in losses due to disrupted air travel and business activities plus increased healthcare expenditures. Thousands died.

It also caused droughts and flooding in other parts of the world with extreme rainfall in Africa and North America and one of Indonesia’s worst droughts on record. The year 1998 ultimately became one of the warmest years on record.

The El Niño and La Niña weather patterns result from complex interactions between the atmosphere and the ocean with significant warming or cooling occurring in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean.

These interactions disturb air flows in the lower atmosphere and lead to localised air-sea interactions that impact weather across the globe.

The drier-than-normal conditions are influenced by two anticyclonic systems active over the southern Indian Ocean and the north-western Pacific Ocean. These systems act as controlling mechanisms, shaping the movement and intensity of dry conditions across regions.

While air-sea interactions shape local impacts of an El Niño, monsoonal winds also help, strengthening it during the summer months (June to August) and weakening it during winter (December to February).

In the summer months in Southeast Asia, southerly winds prevail, blowing northward from Kalimantan and Sumatra. These winds enhance the southwesterly monsoon winds which can blow the smoke-haze from Sumatra and Kalimantan towards Singapore, Peninsular Malaysia, Sarawak, Brunei and Sabah.

During autumn (September to November), the southern part of Southeast Asia (Sumatra and Kalimantan) continues to experience reduced rainfall while conditions in Peninsular Malaysia return to normal. However, in Borneo, the area of reduced rainfall expands northwards, covering the entire island.

This dry weather aids large-scale forest fire outbreaks in southern Sumatra and Kalimantan which result in the haze.

Southeast Asia’s geographical location between the Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean exposes the region to the influence of both El Niño in the Pacific and the Indian Ocean Dipole occurrence.

The dipole is a climate pattern characterised by temperature differences between the western and eastern parts of the Indian Ocean. Similar to El Niño, it affects air-sea weather patterns and ruffles the southern part of Southeast Asia.

If these two climate phenomena occur together, they can bring out the worst in each other causing disaster-scale droughts and haze, especially during the summer and autumn seasons.

The various phases of an El Niño phenomenon, spanning its origin to its influence on regional atmospheric and oceanic processes, is a complex interplay between anti-cyclonic circulations, monsoonal winds, sea surface temperatures and other atmospheric variables.

These interactions collectively shape the drier-than-normal conditions over Southeast Asia during El Niño events. Gaining a comprehensive understanding of these dynamics is essential for accurately predicting and managing the impacts of El Niño on our climate and associated socio-economic sectors.

To mitigate the effects of haze episodes, proactive measures that encompass monitoring and controlling human activities contributing to fire outbreaks are important to ensure the well-being and sustainability of affected regions.

Ester Salimun (PhD) is Senior Lecturer at the Department of Earth Sciences and Environment, Faculty of Science and Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

Her research was partly funded by the Malaysian Ministry of Higher Education (Grant code: FRGS/1/2019/WAB05/UKM/02/3). She declares no conflict of interest.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: In the story “El Nino returns” sent at: 10/07/2023 06:00.

This is a corrected repeat.