We use cookies to improve your experience with Monash. For an optimal experience, we recommend you enable all cookies; alternatively, you can customise which cookies you’re happy for us to use. You may withdraw your consent at any time. To learn more, view our Website Terms and Conditions and Data Protection and Privacy Procedure.

Regulatory creep in the Indian media

Published on October 30, 2024The Indian government continues to enhance its legal and regulatory powers over the country's media outlets.

The rule of the BJP in India has also been marked by a distinct regulatory creep over the media. : Illustration by Michael Joiner, 360info, images via Shahid Tantray and Mekhala Saran CC BY 4.0

The rule of the BJP in India has also been marked by a distinct regulatory creep over the media. : Illustration by Michael Joiner, 360info, images via Shahid Tantray and Mekhala Saran CC BY 4.0

The Indian government continues to enhance its legal and regulatory powers over the country’s media outlets.

India has slipped 19 places in the global press freedom index in the last 10 years.

This coincides with the rule of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) marked by a distinct regulatory creep over the media.

Analysts have pointed out that in its first term beginning in 2014, the BJP government focused on co-opting the mainstream media, delegitimising its critics and denying journalists access to government offices and parliament.

The Narendra Modi government’s preferred mode of communication is to use co-opted media or directly communicate with citizens through social media, TV and radio.

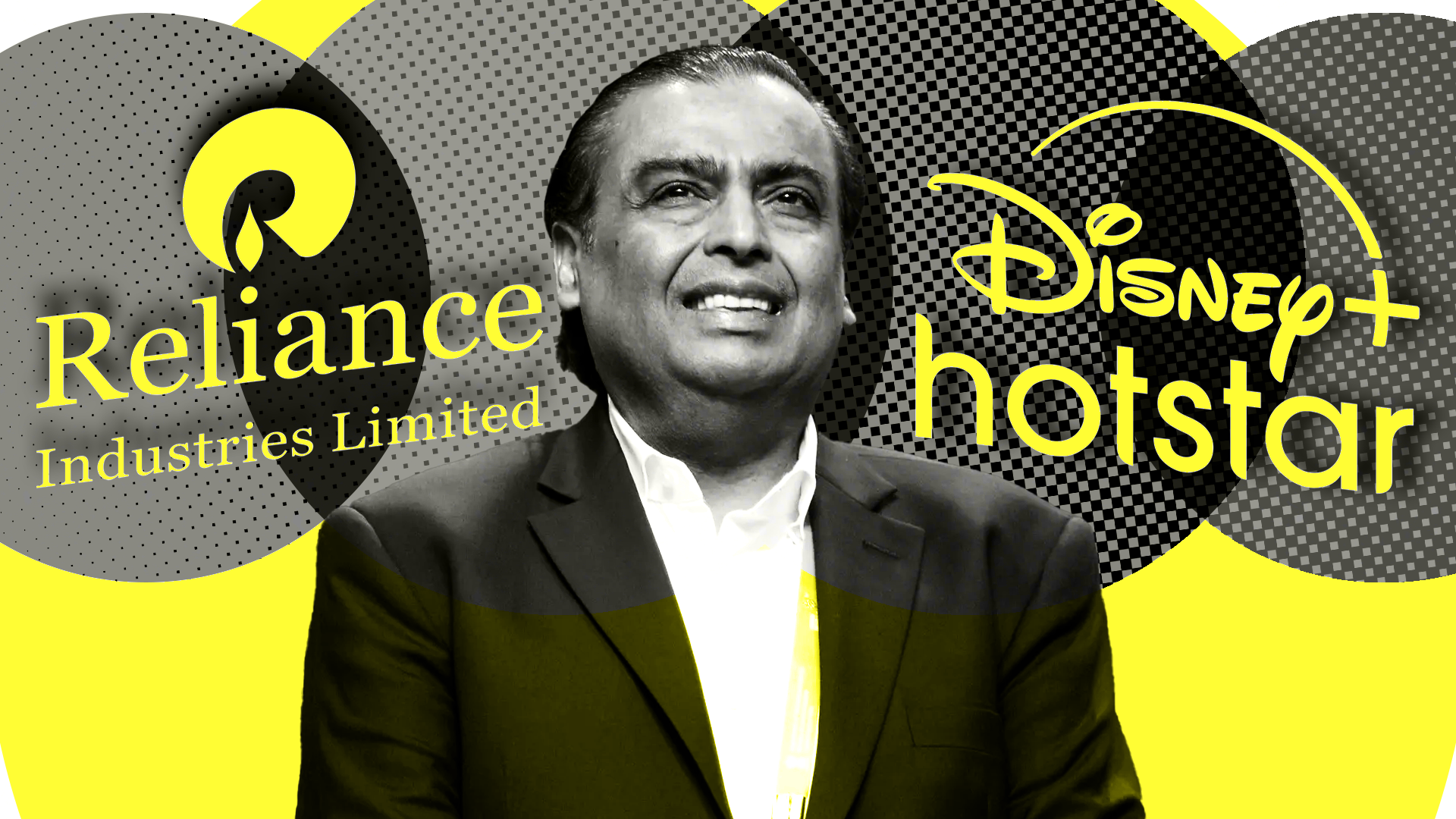

Modi’s government has been accused of facilitating crony capitalism.

Two business groups considered close to the government — led by the two richest men in India, Mukesh Ambani and Gautam Adani — have both bought up a number of media entities, changing the media landscape and creating oligarchies.

In its second term beginning in 2019, the Modi government shifted focus to regulating and controlling the digital media.The proposed Broadcasting Services Regulation Bill, 2023, for example, is meant to expand regulatory oversight to include streaming services (called over-the-top or OTT platforms in India) and digital content.

It proposes mandatory registration, content evaluation committees for self-regulation and a three-tier regulatory system.

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, seeks to define the digital space for regulation, emphasising data handling – preventing unauthorised access to protect data, although journalists apprehend its breaches and misuse by the government.

And through the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Amendment Rules, 2023, the government tried to set up a fact-checking unit manned by its officials to identify “misleading” reportage of government policies.

This has now been stayed by the judiciary.

On April 1, a month prior to the general election which began in May 2024, the government withdrew a draft of the Broadcasting Services (Regulation) Bill which it had put up for limited public discussion.

Although the current state of the bill remains ambiguous and its future unclear, this seems like a tactical retreat.

The Indian government has also used the stringent anti-terrorism law, The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 against journalists. Since 2014, when Narendra Modi came to power, 15 journalists have been charged under this law.

An amendment to the Prevention of Money Laundering Act 2022 is being used against journalists and media platforms receiving funds from different sources.

Journalists have been arrested for sedition, which continues to be a crime. Earlier, sedition had to be seen as inciting the use of force or violence, now under the new legal codes introduced by the Modi government, merely promoting “feelings of separatist activity” whether successful or not, are sufficient to get someone life imprisonment.

The relentless pursuit to enhance regulatory powers over the media by the Modi government continues.

It seeks to create a pro-government media landscape, delegitimising critical journalism.

It remains to be seen how the regulatory creep unfolds further in Modi’s third term.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.