This year is vital for democracy and AI is already wreaking havoc on a news landscape struggling to cope. Smart, proactive legislation could provide protection.

There is a push for accreditation of journalists in Australia so those who sign up to an ethical code of conduct and complaints process can be differentiated from those who do not. : Kenny Eliason via Unsplash Unsplash Licence

There is a push for accreditation of journalists in Australia so those who sign up to an ethical code of conduct and complaints process can be differentiated from those who do not. : Kenny Eliason via Unsplash Unsplash Licence

This year is vital for democracy and AI is already wreaking havoc on a news landscape struggling to cope. Smart, proactive legislation could provide protection.

Almost half the world is voting in national elections this year and AI is the elephant in the room.

There are genuine fears AI-generated or AI-edited deepfakes will potentially manipulate election outcomes not just in the US and UK, but critically in countries such as India.

For that reason, the need for highly trained journalists who can produce trusted, accurate and original reporting is firmly in the spotlight this World Press Freedom Day (May 3).

This year has seen an acceleration in the use of AI technologies, which can boost legitimate political campaigns but also be employed by bad actors to influence outcomes. These tools, combined with lack of regulation on social media platforms, is a grave worry for anyone who supports democracy.

But for those of us preparing the next generation of journalists, it’s a challenge to further enhance the technical and soft skills that lead to excellent public interest journalism.

The deepfakes fear

AI has been used for more than a decade in the US, providing automated earthquake warnings for the Los Angeles Times. But it is now being used by journalists in far smaller newsrooms to, among other things, generate quick rewrites of 50 press releases at a time.

The European Union is leading the way in developing ethical guidelines for dealing with AI that are “human centric”. There are seven requirements that are considered key in the EU for achieving trustworthy AI. They include human agency and oversight; robustness and safety; societal and environmental well-being, and accountability.

But globally, people are concerned. Software company Adobe has just released a Future of Trust Study, which surveyed more than 6,000 people across the US, UK, France and Germany about their experiences encountering misinformation online and concerns about the impact of generative AI.

The study shows more than 80 percent of respondents in each nation were concerned the content they consume online was vulnerable to being altered to mislead or deceive.

A significant number said it was becoming difficult to verify if the content they were consuming online was trustworthy, and most believed that misinformation and harmful deepfakes would impact future elections.

They generally believed governments and technology companies should work together to protect election integrity against deepfakes and misinformation.

Those surveyed were quite right to be fearful, with the recent Solomon Islands election awash with fake information.

The role of verified journalists

While Australia might be lagging with regulation around AI, it has led the way in forcing big tech companies to support the provision of journalism through its News Bargaining code by making them pay local news publishers for news content available on their platforms.

Despite Australia’s world-leading laws, Meta has already warned that it will remove news rather than support its continued existence within Facebook. It’s a move being labelled anti-democratic by Australian politicians.

Having access to balanced news and information, prepared by well-trained journalists is one of the best ways to fight misinformation and disinformation spread across social media.

But that trust only comes when the news is fair and transparent, represents all in the community, and is provided by people who sign up to an ethical framework.

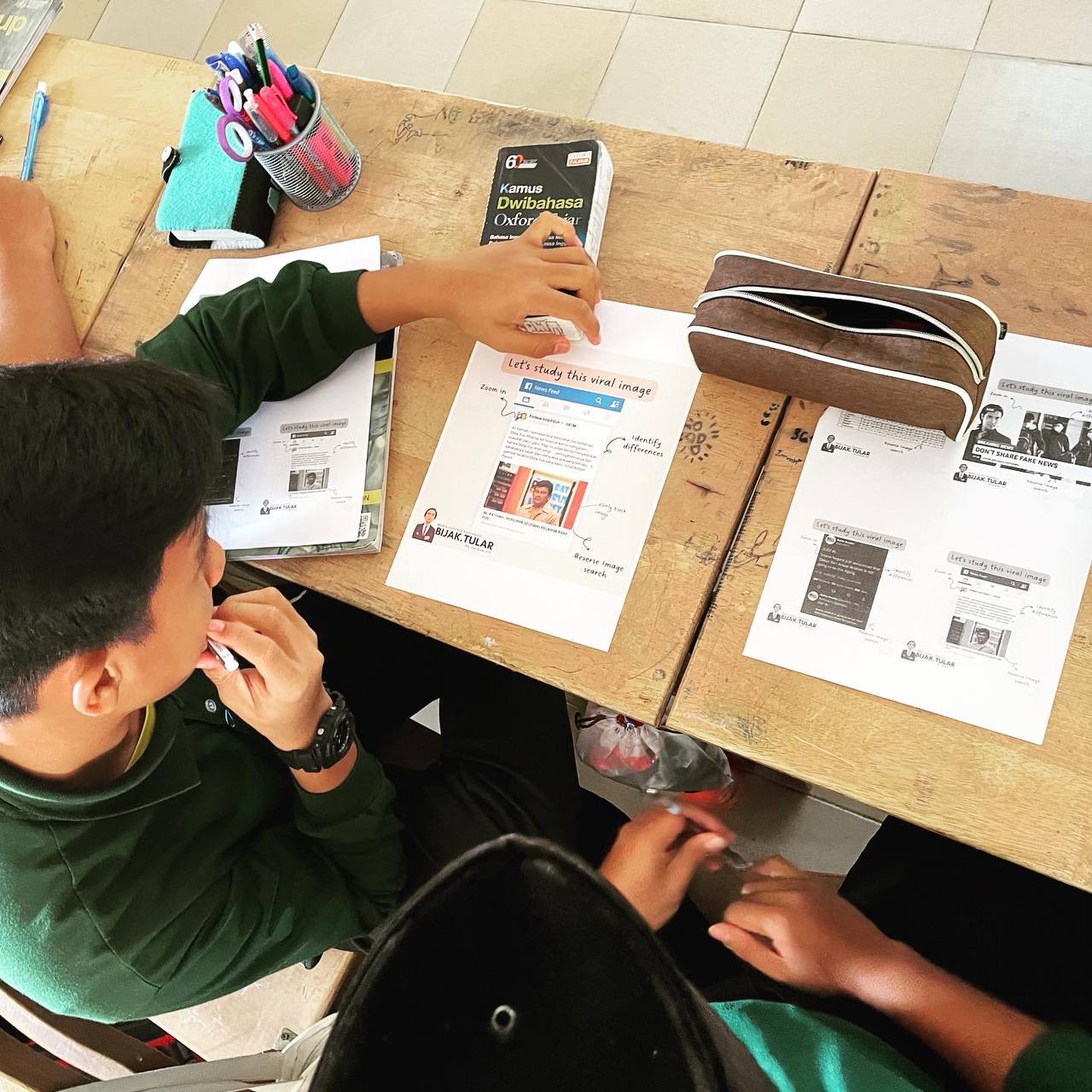

It’s one reason academics are pushing for accreditation of journalists in Australia so those who sign up to an ethical code of conduct and complaints process can be differentiated from those who do not.

While journalists certainly have a lot more to do to rebuild relationships with audiences, that job is almost impossible if we cannot clearly identify who is, and more importantly, who is not a credible and ethical journalist.

Rethinking the news business model

Around the globe, governments, philanthropists and businesses which care about democracy are continuing to look for ways to save the flailing news industry.

Despite a range of initiatives to support journalism, from tax breaks for hiring journalists in New York to philanthropic grants, the number of news deserts continues to rise with the closure of long-running newspapers like the 125-year-old Barrier Truth in Broken Hill, in far west New South Wales.

Australia’s media market is being tracked by Public Interest Journalism Initiative and it has found much resilience in the provision of news across most local government areas with few areas that have no reporting at all.

However, there is very little court reporting in regional Australia, and while regional and city governments are generally well covered, that is less true of regional shires and metropolitical councils.

CEOs more concerned about the financial bottom-line than they are about the provision of news to the public are continuing to close operations.

New Zealand’s long-running television news program, NewsHub, is due to close mid-year with the loss of 200 jobs thanks to a decision by the US media conglomerate Warner Bros Discovery.

The decision was set to leave the state-owned TVNZ network as the only source of free TV news in the entire country until a last-minute deal by the NZ media site Stuff was struck to provide another English-language news program.

Legislation is often slow to catch up with technological innovations but, in a year packed with elections, the stakes have never been so high to keep pace with emerging threats.

The financial pressures on the media industry are not disappearing but, with proactive government support and savvy work from those dedicated to preserving democracy, a way forward is tenable.

Alexandra Wake is an Associate Professor of Journalism at RMIT University and the elected President of the Journalism Education and Research Association of Australia. She is an active leader, educator and researcher in journalism.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.