In Malaysia's post-truth era, information overload and manipulation hinder informed decision-making, demanding media literacy solutions.

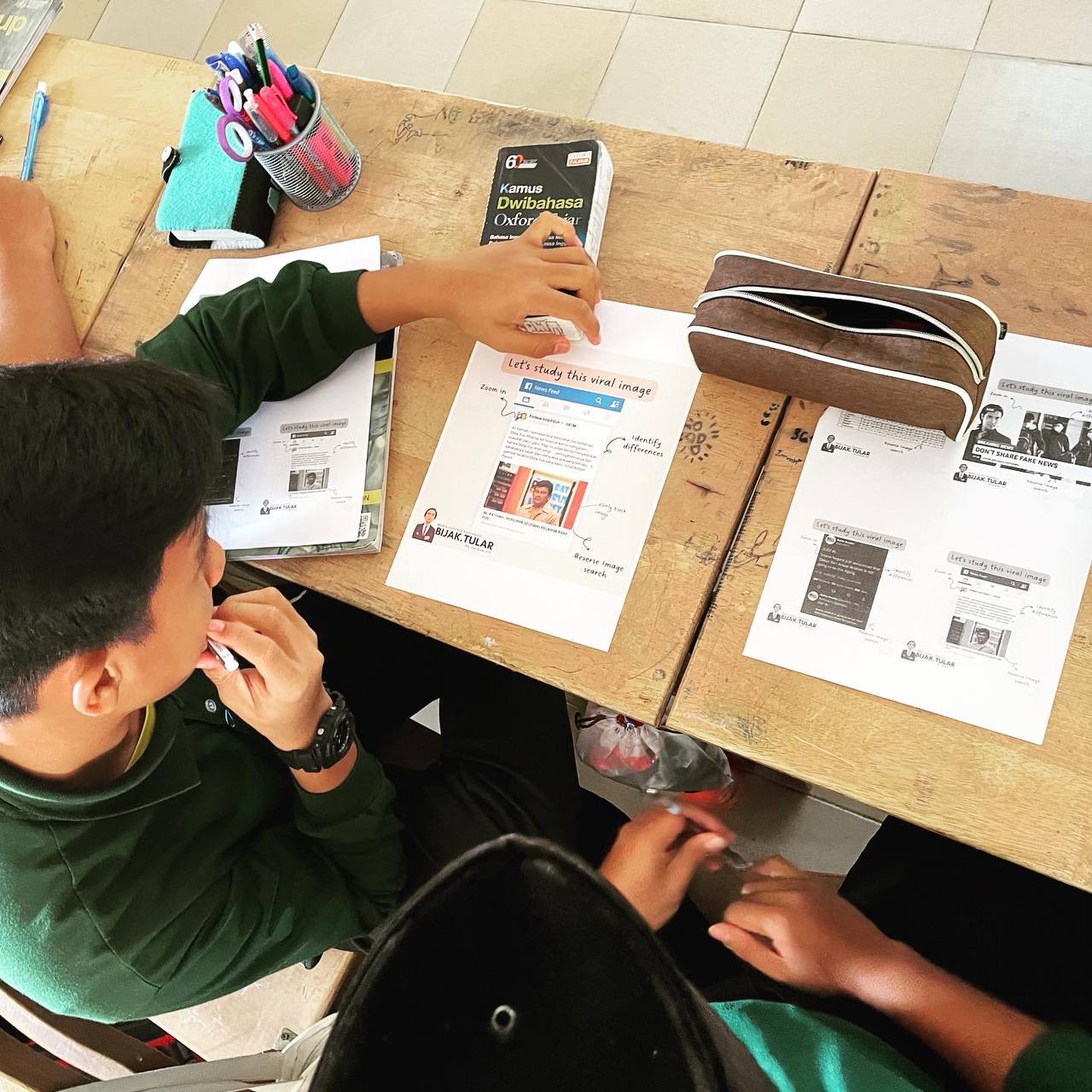

An example of a media literacy awareness workshop called BijakTular aimed to teach students to identify misinformation, disinformation and fabricated news. : Young Southeast Asian Leaders Initiative (Flickr) CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

An example of a media literacy awareness workshop called BijakTular aimed to teach students to identify misinformation, disinformation and fabricated news. : Young Southeast Asian Leaders Initiative (Flickr) CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

In Malaysia’s post-truth era, information overload and manipulation hinder informed decision-making, demanding media literacy solutions.

Misinformation and media literacy has become a touchstone subject for many nations and Malaysia is no different.

So much so, the fact-checking community in Malaysia is evolving, with AI and old-fashioned human beings at the coalface of verifying what’s real and what’s not on social media and other platforms.

This combination of AI and human expertise, reminiscent of an era where fact-checking relied solely on human judgement, highlights the complexities of navigating the digital age.

While Malaysia grapples with press freedom concerns and the “weaponisation” of information, the need for a well-informed society has never been greater.

This underscores the long-term impact of media and information literacy.

There’s a growing reliance on machine learning algorithms for detecting misinformation in the industrial sector. These algorithms analyse large volumes of data and identify potentially false or misleading information.

At the same time, people are manually fact-checking content to verify its accuracy.

In November 2022, Malaysia launched its first fact-checking alliance called JomCheck, to address the spread of mis/disinformation online.

JomCheck aims to be a platform in Malaysia to fight against misinformation. This alliance of professional fact-checkers, journalists, and even students created a dedicated tip line where anyone can submit suspicious claims and get them verified by a trusted source

While this approach may be more time-consuming, it offers a level of nuance and contextual understanding that algorithms sometimes lack.

JomCheck partners collaborated to debunk claims and provide clarification during both the 15th general elections and the 2023 state elections. Other JomCheck alliance partners, such as independent educational groups like Arus Academy, the Media Education For All (ME4A) movement, and the Society of Media and Information Literacy Educators (SMILE), focused on empowering young people through workshops and training sessions.

In April, the Malaysian Ministry of Communications launched ‘AI untuk Rakyat‘ (AI for people) which uses artificial intelligence (AI) to help users verify information they received, avoiding misleading news and falling victim to scams.

The ministry has even urged news consumers to equip themselves with media literacy skills to know how to obtain, consume and read information from credible sources.

By equipping people with the skills to critically evaluate and analyse information, media and information literacy becomes not only an exciting but a vital solution in the fight against misinformation.

Despite the urgent need for this competency, there is no media and information literacy education in Malaysia’s formal education curriculum or syllabus.

Several strategies have been implemented by the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission to address the issue of misinformation and social media abuse.

These include educational initiatives such as Klick Dengan Bijak (click wisely) and the Malaysia ICT Volunteer aimed at empowering Malaysians to become digital citizens and contributing to the development of a smart digital nation.

Besides establishing its own verification platform such as sebenarnya.my, the communications ministry is also working with global digital platforms including Telegram, Tik Tok and Meta on content moderation.

Authorities would request the online platforms to take down content supposedly violating local laws. This has backfired as critics have accused the government of stifling freedom of speech although the government clarified it wanted to remove controversial posts on issues such as race, religion and royalty.

These platforms would review and remove content that is against their community guidelines; otherwise, they then assess if it truly infringes upon local laws as claimed.

While indisputable content such as pornography, scams, illegal sales, and gambling-related material should be erased, questions remain about what qualifies as “misinformation” and “unfavourable content” under local laws.

These laws are highly restrictive and subject to debate, leaving questions about transparency, fairness and power centralisation on digital content moderation.

Despite these efforts, distinguishing genuine signals from the vast array of online content remains challenging, especially given the diverse formats and types of information circulating on social media platforms.

Research emphasises the effectiveness of media and information literacy education in mitigating the spread of online falsehoods, positioning it as a promising long-term and sustainable solution to the widespread of misinformation.

In contrast to Western nations where media and information literacy education is integrated into formal systems, Asian and developing countries face unique socio-cultural and political challenges.

Initial initiatives in developing countries around the world are often supported by international NGOs such as UNESCO and UNICEF, aiming to enhance media and information literacy competence among young students, fostering critical thinking towards media content, and promoting human rights-oriented content creation.

In countries such as China and Vietnam, efforts are made to equip students with media skills while advocating for children’s rights. Singapore has established comprehensive guidelines and modelled programs from its Ministry of Education to integrate information literacy across various educational levels. However, there’s a noticeable gap in attention and implementation regarding media literacy.

Hong Kong has adopted a unique network model strategy, fostering grassroots community movements to promote media and information literacy education by leveraging diverse sources and facilitating its development.

Overall, combating online falsehood should not solely focus on identifying misinformation and inaccuracy. Instead, it should empower media content consumers to recognise bias in all sources of information.

To achieve this, concepts such as objectivity, impartiality, fairness, and balance should be integrated within the context of media and information literacy education.

Kow Kwan Yee is a lecturer at the School of Communication & Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, Malaysia. Her research interests include media literacy education, press freedom, media reform, and communication policies and practices.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Editors Note: In the story “Press Freedom” sent at: 03/05/2024 13:34.

This is a corrected repeat.