We use cookies to improve your experience with Monash. For an optimal experience, we recommend you enable all cookies; alternatively, you can customise which cookies you’re happy for us to use. You may withdraw your consent at any time. To learn more, view our Website Terms and Conditions and Data Protection and Privacy Procedure.

Pakistan readies itself for an orchestrated election

Published on February 7, 2024The Pakistan Army manipulates the election process to get a friendly government in place.

Pakistan will have general elections on Thursday, February 8. : Michael Joiner, 360info CCBY4.0

Pakistan will have general elections on Thursday, February 8. : Michael Joiner, 360info CCBY4.0

The Pakistan Army manipulates the election process to get a friendly government in place.

Pakistan, undergoing a dire economic crisis, will hold its national election on February 8.

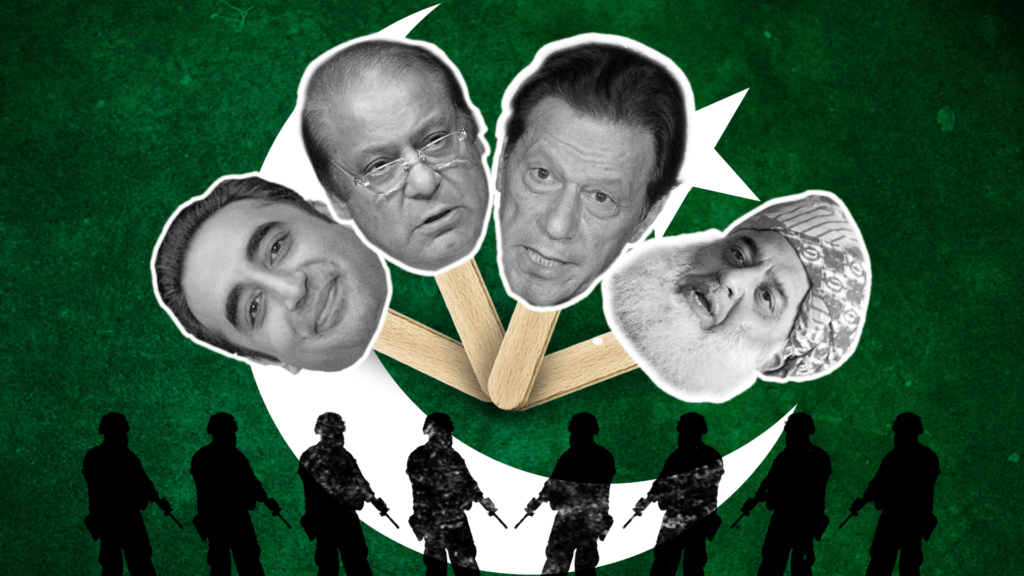

The election process is being choreographed by the Pakistan Army through a caretaker government, constitutionally mandated to hold the election.

The army has directly ruled Pakistan for more than three decades. It has weakened democratic institutions to such an extent that it continues to influence policy even when not directly in power.

This general election will be no exception.

The previously elected government headed by cricketing icon and wildly popular leader Imran Khan, head of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), was a protégé of the army until he fell afoul of it and was ousted through a vote of no confidence.

Now he has been charged and indicted in several criminal cases. He has received three prison terms, virtually on the eve of the polls.

Imran’s conviction, which disqualifies him from contesting, is unlikely to be set aside by appealing to the higher judiciary before the February 8 election.

The court proceedings took place inside the prison and the sentencing seems deliberately timed to demoralise his party and supporters on the eve of the elections.

Imran’s party and its top leadership is being systematically destroyed not only through the judicial process but also through an unprecedented crackdown on PTI leaders across the country in order to persuade them to withdraw from the electoral contest.

To top it all, his party has been denied the use of its official symbol – a cricket bat – by the Election Commission, and subsequently endorsed by the judiciary.

His party’s candidates will therefore be forced to contest as independents under a different election symbol in each constituency. This will make it difficult for rural and uneducated voters to recognise the party.

Simultaneously, former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif of Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) or PML (N), until recently a fugitive from justice and in self-exile in the UK, has been brought back home.

In his case, the judiciary had been accommodating and has not only granted him bail in all the cases pending against him and allowed him to contest the polls.

His potential march to electoral victory is widely believed to be choreographed by the military establishment.

Under these circumstances, neither human rights groups nor public intellectuals in Pakistan expect the general election to be free and fair.

The main reason for this is that the electoral landscape has been manipulated to keep the largest political party, PTI, and the most popular political leader in the country, Imran Khan, out of the election.

However, the sentencing of Imran may throw a wrench in the army’s plans.

The repressive tactics of the “establishment” (Pakistani code for the army and the bureaucratic elite), especially the long prison sentences handed to Imran, could infuse a new wave of anger in the party’s popular support base.

This could result either in a “sympathy wave” among voters for the party’s candidates contesting as independents. They could even abstain from voting. Either way, the resulting political polarisation will last beyond the results of the one-sided elections, fuelling political instability.

However carefully orchestrated, the outcome of the elections will be hard to predict. Local patronage and allegiance networks favour older parties — the PTI is relatively new, set up in 1996 and winning its first National Assembly seat in 2002.

The urban-rural balance has changed because of expanding urbanisation. There is also the unpredictability associated with first time voters — 23.5 million new voters have been added since the last election of 2018.

The other imponderables are the overall voter turnout and the role of spoilers such as the Istehkam-i-Pakistan, a King’s Party set up with PTI deserters.

The dire state of the Pakistani economy is a structural problem that will have to be faced by whoever forms the next government.

The country’s debt burden is high, prices of staples are rising by the day and the national currency is plummeting. Its faltering economy has pushed Pakistan to the brink of default –it barely managed to revive a long-stalled $6 billion International Monetary Fund bailout package in June 2023.

Sharif, a three-time PM and head of a business empire himself, has a track record of development and putting the economy on track.

However, if the elections are seen as controversial and political turmoil follows, then even he may not be able to bring about stability necessary by introducing harsh structural reforms which the IMF bailouts mandate for tackling the crisis.